BUDDHISM

Main menu

Personal tools

Contents

hide

- (Top)

- Etymology

- The Buddha

- WorldviewToggle Worldview subsection

- Paths to liberationToggle Paths to liberation subsection

- Common practicesToggle Common practices subsection

- TextsToggle Texts subsection

- HistoryToggle History subsection

- Schools and traditions

- Monasteries and temples

- In the modern eraToggle In the modern era subsection

- Cultural influence

- Demographics

- Criticism

- See also

- Explanatory notesToggle Explanatory notes subsection

- References

- Sources

- External links

Buddhism

222 languages

Tools

Appearancehide

Text

- SmallStandardLarge

Width

- StandardWide

Color (beta)

- AutomaticLightDark

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

“Buddhadharma” and “Buddhist” redirect here. For the magazine, see Buddhadharma: The Practitioner’s Quarterly. For the racehorse, see Buddhist (horse).

| Part of a series on |

| Buddhism |

|---|

| GlossaryIndexOutline |

| showHistory |

| showDharmaConcepts |

| showBuddhist texts |

| showPractices |

| showNirvāṇa |

| showTraditions |

| showBuddhism by country |

| Buddhism portal |

| vte |

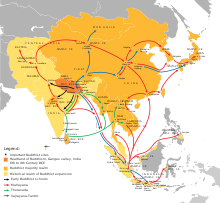

Buddhism (/ˈbʊdɪzəm/ BUUD-ih-zəm, US also /ˈbuːd-/ BOOD-),[1][2][3] also known as Buddha Dharma, is an Indian religion[a] and philosophical tradition based on teachings attributed to the Buddha, a wandering teacher who lived in the 6th or 5th century BCE.[7] It is the world’s fourth-largest religion,[8][9] with over 520 million followers, known as Buddhists, who comprise seven percent of the global population.[10][11] It arose in the eastern Gangetic plain as a śramaṇa movement in the 5th century BCE, and gradually spread throughout much of Asia. Buddhism has subsequently played a major role in Asian culture and spirituality, eventually spreading to the West in the 20th century.[12]

According to tradition, the Buddha instructed his followers in a path of development which leads to awakening and full liberation from dukkha (lit. ’suffering or unease’[note 1]). He regarded this path as a Middle Way between extremes such as asceticism or sensual indulgence.[17][18] Teaching that dukkha arises alongside attachment or clinging, the Buddha advised meditation practices and ethical precepts rooted in non-harming. Widely observed teachings include the Four Noble Truths, the Noble Eightfold Path, and the doctrines of dependent origination, karma, and the three marks of existence. Other commonly observed elements include the Triple Gem, the taking of monastic vows, and the cultivation of perfections (pāramitā).[19]

The Buddhist canon is vast, with many different textual collections in different languages (such as Sanskrit, Pali, Tibetan, and Chinese).[20] Buddhist schools vary in their interpretation of the paths to liberation (mārga) as well as the relative importance and “canonicity” assigned to various Buddhist texts, and their specific teachings and practices.[21][22] Two major extant branches of Buddhism are generally recognized by scholars: Theravāda (lit. ’School of the Elders’) and Mahāyāna (lit. ’Great Vehicle’). The Theravada tradition emphasizes the attainment of nirvāṇa (lit. ’extinguishing’) as a means of transcending the individual self and ending the cycle of death and rebirth (saṃsāra),[23][24][25] while the Mahayana tradition emphasizes the Bodhisattva ideal, in which one works for the liberation of all sentient beings. Additionally, Vajrayāna (lit. ’Indestructible Vehicle’), a body of teachings incorporating esoteric tantric techniques, may be viewed as a separate branch or tradition within Mahāyāna.[26]

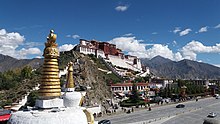

The Theravāda branch has a widespread following in Sri Lanka as well as in Southeast Asia, namely Myanmar, Thailand, Laos, and Cambodia. The Mahāyāna branch—which includes the East Asian traditions of Tiantai, Chan, Pure Land, Zen, Nichiren, and Tendai is predominantly practised in Nepal, Bhutan, China, Malaysia, Vietnam, Taiwan, Korea, and Japan. Tibetan Buddhism, a form of Vajrayāna, is practised in the Himalayan states as well as in Mongolia[27] and Russian Kalmykia.[28] Japanese Shingon also preserves the Vajrayana tradition as transmitted to China. Historically, until the early 2nd millennium, Buddhism was widely practiced in the Indian subcontinent before declining there;[29][30][31] it also had a foothold to some extent elsewhere in Asia, namely Afghanistan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, and Tajikistan.[32]

Etymology

The names Buddha Dharma and Bauddha Dharma come from Sanskrit: बुद्ध धर्म and बौद्ध धर्म respectively (“doctrine of the Enlightened One” and “doctrine of Buddhists”). The term Dharmavinaya comes from Sanskrit: धर्मविनय, literally meaning “doctrines [and] disciplines”.[33]

The Buddha (“the Awakened One”) was a Śramaṇa who lived in South Asia c. 6th or 5th century BCE.[34][35] Followers of Buddhism, called Buddhists in English, referred to themselves as Sakyan-s or Sakyabhiksu in ancient India.[36][37] Buddhist scholar Donald S. Lopez asserts they also used the term Bauddha,[38] although scholar Richard Cohen asserts that that term was used only by outsiders to describe Buddhists.[39]

The Buddha

Main article: The Buddha

Details of the Buddha’s life are mentioned in many Early Buddhist Texts but are inconsistent. His social background and life details are difficult to prove, and the precise dates are uncertain, although the 5th century BCE seems to be the best estimate.[40][note 2]

Early texts have the Buddha’s family name as “Gautama” (Pali: Gotama), while some texts give Siddhartha as his surname. He was born in Lumbini, present-day Nepal and grew up in Kapilavastu,[note 3] a town in the Ganges Plain, near the modern Nepal–India border, and he spent his life in what is now modern Bihar[note 4] and Uttar Pradesh.[48][40] Some hagiographic legends state that his father was a king named Suddhodana, his mother was Queen Maya.[49] Scholars such as Richard Gombrich consider this a dubious claim because a combination of evidence suggests he was born in the Shakya community, which was governed by a small oligarchy or republic-like council where there were no ranks but where seniority mattered instead.[50] Some of the stories about the Buddha, his life, his teachings, and claims about the society he grew up in may have been invented and interpolated at a later time into the Buddhist texts.[51][52]

Various details about the Buddha’s background are contested in modern scholarship. For example, Buddhist texts assert that Buddha described himself as a kshatriya (warrior class), but Gombrich writes that little is known about his father and there is no proof that his father even knew the term kshatriya.[53] (Mahavira, whose teachings helped establish the ancient religion Jainism, is also claimed to be ksatriya by his early followers.[54])

According to early texts such as the Pali Ariyapariyesanā-sutta (“The discourse on the noble quest”, MN 26) and its Chinese parallel at MĀ 204, Gautama was moved by the suffering (dukkha) of life and death, and its endless repetition due to rebirth.[55] He thus set out on a quest to find liberation from suffering (also known as “nirvana“).[56] Early texts and biographies state that Gautama first studied under two teachers of meditation, namely Āḷāra Kālāma (Sanskrit: Arada Kalama) and Uddaka Ramaputta (Sanskrit: Udraka Ramaputra), learning meditation and philosophy, particularly the meditative attainment of “the sphere of nothingness” from the former, and “the sphere of neither perception nor non-perception” from the latter.[57][58][note 5]

Finding these teachings to be insufficient to attain his goal, he turned to the practice of severe asceticism, which included a strict fasting regime and various forms of breath control.[61] This too fell short of attaining his goal, and then he turned to the meditative practice of dhyana. He famously sat in meditation under a Ficus religiosa tree—now called the Bodhi Tree—in the town of Bodh Gaya and attained “Awakening” (Bodhi).[62][according to whom?]

According to various early texts like the Mahāsaccaka-sutta, and the Samaññaphala Sutta, on awakening, the Buddha gained insight into the workings of karma and his former lives, as well as achieving the ending of the mental defilements (asavas), the ending of suffering, and the end of rebirth in saṃsāra.[61] This event also brought certainty about the Middle Way as the right path of spiritual practice to end suffering.[17][18] As a fully enlightened Buddha, he attracted followers and founded a Sangha (monastic order).[63] He spent the rest of his life teaching the Dharma he had discovered, and then died, achieving “final nirvana“, at the age of 80 in Kushinagar, India.[64][43][according to whom?]

The Buddha’s teachings were propagated by his followers, which in the last centuries of the 1st millennium BCE became various Buddhist schools of thought, each with its own basket of texts containing different interpretations and authentic teachings of the Buddha;[65][66][67] these over time evolved into many traditions of which the more well known and widespread in the modern era are Theravada, Mahayana and Vajrayana Buddhism.[68][69]

Worldview

Main article: Glossary of Buddhism

The term “Buddhism” is an occidental neologism, commonly (and “rather roughly” according to Donald S. Lopez Jr.) used as a translation for the Dharma of the Buddha, fójiào in Chinese, bukkyō in Japanese, nang pa sangs rgyas pa’i chos in Tibetan, buddhadharma in Sanskrit, buddhaśāsana in Pali.[70]

Four Noble Truths – dukkha and its ending

Main articles: Dukkha and Four Noble Truths

The Four Noble Truths, or the truths of the Noble Ones,[71] express the basic orientation of Buddhism: we crave and cling to impermanent states and things, which is dukkha, “incapable of satisfying” and painful.[72][73] This keeps us caught in saṃsāra, the endless cycle of repeated rebirth, dukkha and dying again.[note 6]

But there is a way to liberation from this endless cycle[79] to the state of nirvana, namely following the Noble Eightfold Path.[note 7]

The truth of dukkha is the basic insight that life in this mundane world, with its clinging and craving to impermanent states and things[72] is dukkha, and unsatisfactory.[74][85][web 1] Dukkha can be translated as “incapable of satisfying”,[web 5] “the unsatisfactory nature and the general insecurity of all conditioned phenomena“; or “painful”.[72][73] Dukkha is most commonly translated as “suffering”, but this is inaccurate, since it refers not to episodic suffering, but to the intrinsically unsatisfactory nature of temporary states and things, including pleasant but temporary experiences.[note 8] We expect happiness from states and things which are impermanent, and therefore cannot attain real happiness.

The Four Noble Truths are:

- dukkha (“not being at ease”, “suffering”) is an innate characteristic of the perpetual cycle (samsara, lit. ’wandering’) of grasping at things, ideas and habits

- samudaya (origin, arising, combination; “cause”): dukkha is caused by taṇhā (“craving,” “desire” or “attachment,” literally “thirst”)

- nirodha (cessation, ending, confinement): dukkha can be ended or contained by the confinement or letting go of taṇhā

- marga (path) is the path leading to the confinement of taṇhā and dukkha, classically the Noble Eightfold Path but sometimes other paths to liberation

Three marks of existence

Main article: Three marks of existence

Buddhism teaches that the idea that anything is permanent or that there is self in any being is ignorance or misperception (avijjā), and that this is the primary source of clinging and dukkha.[91][92][93]

Ignorance is countered by insight (paññā); most schools of Buddhism, therefore, teach three marks of existence, which fundamentally characterize all phenomena:[94]

- Dukkha: unease, suffering

- Anicca: impermanence

- Anattā: non-self; living things have no permanent immanent soul or essence[95][96][97]

Some schools describe four characteristics or “four seals of the Dharma”, adding to the above

The cycle of rebirth

Saṃsāra

Main article: Saṃsāra (Buddhism)

Saṃsāra means “wandering” or “world”, with the connotation of cyclic, circuitous change.[100][101] It refers to the theory of rebirth and “cyclicality of all life, matter, existence”, a fundamental assumption of Buddhism, as with all major Indian religions.[101][102] Samsara in Buddhism is considered to be dukkha, unsatisfactory and painful,[103] perpetuated by desire and avidya (ignorance), and the resulting karma.[101][104][105] Liberation from this cycle of existence, nirvana, has been the foundation and the most important historical justification of Buddhism.[106][107]

Buddhist texts assert that rebirth can occur in six realms of existence, namely three good realms (heavenly, demi-god, human) and three evil realms (animal, hungry ghosts, hellish).[note 9] Samsara ends if a person attains nirvana, the “blowing out” of the afflictions through insight into impermanence and “non-self“.[109][110][111]

Rebirth

Main article: Rebirth (Buddhism)

Rebirth refers to a process whereby beings go through a succession of lifetimes as one of many possible forms of sentient life, each running from conception to death.[112] In Buddhist thought, this rebirth does not involve a soul or any fixed substance. This is because the Buddhist doctrine of anattā (Sanskrit: anātman, no-self doctrine) rejects the concepts of a permanent self or an unchanging, eternal soul found in other religions.[113][114]

The Buddhist traditions have traditionally disagreed on what it is in a person that is reborn, as well as how quickly the rebirth occurs after death.[115][116] Some Buddhist traditions assert that “no self” doctrine means that there is no enduring self, but there is avacya (inexpressible) personality (pudgala) which migrates from one life to another.[115] The majority of Buddhist traditions, in contrast, assert that vijñāna (a person’s consciousness) though evolving, exists as a continuum and is the mechanistic basis of what undergoes the rebirth process.[74][115] The quality of one’s rebirth depends on the merit or demerit gained by one’s karma (i.e., actions), as well as that accrued on one’s behalf by a family member.[note 10] Buddhism also developed a complex cosmology to explain the various realms or planes of rebirth.[103]

Karma

Main article: Karma in Buddhism

In Buddhism, karma (from Sanskrit: “action, work”) drives saṃsāra—the endless cycle of suffering and rebirth for each being. Good, skilful deeds (Pāli: kusala) and bad, unskilful deeds (Pāli: akusala) produce “seeds” in the unconscious receptacle (ālaya) that mature later either in this life or in a subsequent rebirth.[118][119] The existence of karma is a core belief in Buddhism, as with all major Indian religions, and it implies neither fatalism nor that everything that happens to a person is caused by karma.[120] (Diseases and suffering induced by the disruptive actions of other people are examples of non-karma suffering.[120])

A central aspect of Buddhist theory of karma is that intent (cetanā) matters and is essential to bring about a consequence or phala “fruit” or vipāka “result”.[121] The emphasis on intent in Buddhism marks a difference from the karmic theory of Jainism, where karma accumulates with or without intent.[122][123] The emphasis on intent is also found in Hinduism, and Buddhism may have influenced karma theories of Hinduism.[124]

In Buddhism, good or bad karma accumulates even if there is no physical action, and just having ill or good thoughts creates karmic seeds; thus, actions of body, speech or mind all lead to karmic seeds.[120] In the Buddhist traditions, life aspects affected by the law of karma in past and current births of a being include the form of rebirth, realm of rebirth, social class, character and major circumstances of a lifetime.[120][125][126] According to the theory, it operates like the laws of physics, without external intervention, on every being in all six realms of existence including human beings and gods.[120][127]

A notable aspect of the karma theory in modern Buddhism is merit transfer.[128][129] A person accumulates merit not only through intentions and ethical living, but also is able to gain merit from others by exchanging goods and services, such as through dāna (charity to monks or nuns).[130] The theory also states a person can transfer one’s own good karma to living family members and ancestors.[129]

This Buddhist idea may have roots in the quid-pro-quo exchange beliefs of the Hindu Vedic rituals.[131] The “karma merit transfer” concept has been controversial, not accepted in later Jainism and Hinduism traditions, unlike Buddhism where it was adopted in ancient times and remains a common practice.[128] According to Bruce Reichenbach, the “merit transfer” idea was generally absent in early Buddhism and may have emerged with the rise of Mahayana Buddhism; he adds that while major Hindu schools such as Yoga, Advaita Vedanta and others do not believe in merit transfer, some bhakti Hindu traditions later adopted the idea just like Buddhism.[132]

Liberation

Main articles: Moksha and Nirvana (Buddhism)

The cessation of the kleshas and the attainment of nirvana (nibbāna), with which the cycle of rebirth ends, has been the primary and the soteriological goal of the Buddhist path for monastic life since the time of the Buddha.[81][133][134] The term “path” is usually taken to mean the Noble Eightfold Path, but other versions of “the path” can also be found in the Nikayas.[note 11] In some passages in the Pali Canon, a distinction is being made between right knowledge or insight (sammā-ñāṇa), and right liberation or release (sammā-vimutti), as the means to attain cessation and liberation.[136][137]

Nirvana literally means “blowing out, quenching, becoming extinguished”.[138][139] In early Buddhist texts, it is the state of restraint and self-control that leads to the “blowing out” and the ending of the cycles of sufferings associated with rebirths and redeaths.[140][141][142] Many later Buddhist texts describe nirvana as identical with anatta with complete “emptiness, nothingness”.[143][144][145][note 12] In some texts, the state is described with greater detail, such as passing through the gate of emptiness (sunyata)—realising that there is no soul or self in any living being, then passing through the gate of signlessness (animitta)—realising that nirvana cannot be perceived, and finally passing through the gate of wishlessness (apranihita)—realising that nirvana is the state of not even wishing for nirvana.[133][147][note 13]

The nirvana state has been described in Buddhist texts partly in a manner similar to other Indian religions, as the state of complete liberation, enlightenment, highest happiness, bliss, fearlessness, freedom, permanence, non-dependent origination, unfathomable, and indescribable.[149][150] It has also been described in part differently, as a state of spiritual release marked by “emptiness” and realisation of non-self.[151][152][153][note 14]

While Buddhism considers the liberation from saṃsāra as the ultimate spiritual goal, in traditional practice, the primary focus of a vast majority of lay Buddhists has been to seek and accumulate merit through good deeds, donations to monks and various Buddhist rituals in order to gain better rebirths rather than nirvana.[156][157][note 15]

Dependent arising

Main articles: Pratītyasamutpāda and Twelve Nidānas

Pratityasamutpada, also called “dependent arising, or dependent origination”, is the Buddhist theory to explain the nature and relations of being, becoming, existence and ultimate reality. Buddhism asserts that there is nothing independent, except the state of nirvana.[160] All physical and mental states depend on and arise from other pre-existing states, and in turn from them arise other dependent states while they cease.[161]

The ‘dependent arisings’ have a causal conditioning, and thus Pratityasamutpada is the Buddhist belief that causality is the basis of ontology, not a creator God nor the ontological Vedic concept called universal Self (Brahman) nor any other ‘transcendent creative principle’.[162][163] However, Buddhist thought does not understand causality in terms of Newtonian mechanics; rather it understands it as conditioned arising.[164][165] In Buddhism, dependent arising refers to conditions created by a plurality of causes that necessarily co-originate a phenomenon within and across lifetimes, such as karma in one life creating conditions that lead to rebirth in one of the realms of existence for another lifetime.[166][167][168]

Buddhism applies the theory of dependent arising to explain origination of endless cycles of dukkha and rebirth, through Twelve Nidānas or “twelve links”. It states that because Avidyā (ignorance) exists, Saṃskāras (karmic formations) exist; because Saṃskāras exist therefore Vijñāna (consciousness) exists; and in a similar manner it links Nāmarūpa (the sentient body), Ṣaḍāyatana (our six senses), Sparśa (sensory stimulation), Vedanā (feeling), Taṇhā (craving), Upādāna (grasping), Bhava (becoming), Jāti (birth), and Jarāmaraṇa (old age, death, sorrow, and pain).[169][170] By breaking the circuitous links of the Twelve Nidanas, Buddhism asserts that liberation from these endless cycles of rebirth and dukkha can be attained.[171]

Not-Self and Emptiness

Main articles: Anātman and Śūnyatā

| The Five Aggregates (pañca khandha) according to the Pali Canon. | ||||

| form (rūpa) 4 elements (mahābhūta) ↓ contact (phassa) ↓↑ consciousness (viññāna) | → ← ← | mental factors (cetasika) feeling (vedanā) perception (sañña) formation (saṅkhāra) | ||

| Form is derived from the Four Great Elements.Consciousness arises from other aggregates.Mental Factors arise from the Contact of Consciousness and other aggregates. | ||||

| Source: MN 109 (Thanissaro, 2001) | diagram details | ||||

A related doctrine in Buddhism is that of anattā (Pali) or anātman (Sanskrit). It is the view that there is no unchanging, permanent self, soul or essence in phenomena.[172] The Buddha and Buddhist philosophers who follow him such as Vasubandhu and Buddhaghosa, generally argue for this view by analyzing the person through the schema of the five aggregates, and then attempting to show that none of these five components of personality can be permanent or absolute.[173] This can be seen in Buddhist discourses such as the Anattalakkhana Sutta.

“Emptiness” or “voidness” (Skt: Śūnyatā, Pali: Suññatā), is a related concept with many different interpretations throughout the various Buddhisms. In early Buddhism, it was commonly stated that all five aggregates are void (rittaka), hollow (tucchaka), coreless (asāraka), for example as in the Pheṇapiṇḍūpama Sutta (SN 22:95).[174] Similarly, in Theravada Buddhism, it often means that the five aggregates are empty of a Self.[175]

Emptiness is a central concept in Mahāyāna Buddhism, especially in Nagarjuna‘s Madhyamaka school, and in the Prajñāpāramitā sutras. In Madhyamaka philosophy, emptiness is the view which holds that all phenomena are without any svabhava (literally “own-nature” or “self-nature”), and are thus without any underlying essence, and so are “empty” of being independent.[example needed] This doctrine sought to refute the heterodox theories of svabhava circulating at the time.[176]

The Three Jewels

Main article: Three Jewels

All forms of Buddhism revere and take spiritual refuge in the “three jewels” (triratna): Buddha, Dharma and Sangha.[177]

Buddha

Main article: Buddhahood

While all varieties of Buddhism revere “Buddha” and “buddhahood”, they have different views on what these are. Regardless of their interpretation, the concept of Buddha is central to all forms of Buddhism.

In Theravada Buddhism, a Buddha is someone who has become awake through their own efforts and insight. They have put an end to their cycle of rebirths and have ended all unwholesome mental states which lead to bad action and thus are morally perfected.[178] While subject to the limitations of the human body in certain ways (for example, in the early texts, the Buddha suffers from backaches), a Buddha is said to be “deep, immeasurable, hard-to-fathom as is the great ocean”, and also has immense psychic powers (abhijñā).[179] Theravada generally sees Gautama Buddha (the historical Buddha Sakyamuni) as the only Buddha of the current era.[citation needed]

Mahāyāna Buddhism meanwhile, has a vastly expanded cosmology, with various Buddhas and other holy beings (aryas) residing in different realms. Mahāyāna texts not only revere numerous Buddhas besides Shakyamuni, such as Amitabha and Vairocana, but also see them as transcendental or supramundane (lokuttara) beings.[180] Mahāyāna Buddhism holds that these other Buddhas in other realms can be contacted and are able to benefit beings in this world.[181] In Mahāyāna, a Buddha is a kind of “spiritual king”, a “protector of all creatures” with a lifetime that is countless of eons long, rather than just a human teacher who has transcended the world after death.[182] Shakyamuni’s life and death on earth is then usually understood as a “mere appearance” or “a manifestation skilfully projected into earthly life by a long-enlightened transcendent being, who is still available to teach the faithful through visionary experiences”.[182][183]

Dharma

Main article: Dharma

The second of the three jewels is “Dharma” (Pali: Dhamma), which in Buddhism refers to the Buddha’s teaching, which includes all of the main ideas outlined above. While this teaching reflects the true nature of reality, it is not a belief to be clung to, but a pragmatic teaching to be put into practice. It is likened to a raft which is “for crossing over” (to nirvana) not for holding on to.[184] It also refers to the universal law and cosmic order which that teaching both reveals and relies upon.[185] It is an everlasting principle which applies to all beings and worlds. In that sense it is also the ultimate truth and reality about the universe, it is thus “the way that things really are”.

Sangha

Main articles: Sangha, Bodhisattva, and Arhat

The third “jewel” which Buddhists take refuge in is the “Sangha”, which refers to the monastic community of monks and nuns who follow Gautama Buddha’s monastic discipline which was “designed to shape the Sangha as an ideal community, with the optimum conditions for spiritual growth.”[186] The Sangha consists of those who have chosen to follow the Buddha’s ideal way of life, which is one of celibate monastic renunciation with minimal material possessions (such as an alms bowl and robes).[187]

The Sangha is seen as important because they preserve and pass down Buddha Dharma. As Gethin states “the Sangha lives the teaching, preserves the teaching as Scriptures and teaches the wider community. Without the Sangha there is no Buddhism.”[188] The Sangha also acts as a “field of merit” for laypersons, allowing them to make spiritual merit or goodness by donating to the Sangha and supporting them. In return, they keep their duty to preserve and spread the Dharma everywhere for the good of the world.[189]

There is also a separate definition of Sangha, referring to those who have attained any stage of awakening, whether or not they are monastics. This sangha is called the āryasaṅgha “noble Sangha”.[190] All forms of Buddhism generally reveres these āryas (Pali: ariya, “noble ones” or “holy ones”) who are spiritually attained beings. Aryas have attained the fruits of the Buddhist path.[191] Becoming an arya is a goal in most forms of Buddhism. The āryasaṅgha includes holy beings such as bodhisattvas, arhats and stream-enterers.[citation needed]

Other key Mahāyāna views

Main articles: Yogachara and Buddha-nature

Mahāyāna Buddhism also differs from Theravada and the other schools of early Buddhism in promoting several unique doctrines which are contained in Mahāyāna sutras and philosophical treatises.

One of these is the unique interpretation of emptiness and dependent origination found in the Madhyamaka school. Another very influential doctrine for Mahāyāna is the main philosophical view of the Yogācāra school variously, termed Vijñaptimātratā-vāda (“the doctrine that there are only ideas” or “mental impressions”) or Vijñānavāda (“the doctrine of consciousness”). According to Mark Siderits, what classical Yogācāra thinkers like Vasubandhu had in mind is that we are only ever aware of mental images or impressions, which may appear as external objects, but “there is actually no such thing outside the mind”.[192] There are several interpretations of this main theory, many scholars see it as a type of Idealism, others as a kind of phenomenology.[193]

Another very influential concept unique to Mahāyāna is that of “Buddha-nature” (buddhadhātu) or “Tathagata-womb” (tathāgatagarbha). Buddha-nature is a concept found in some 1st-millennium CE Buddhist texts, such as the Tathāgatagarbha sūtras. According to Paul Williams these Sutras suggest that ‘all sentient beings contain a Tathagata’ as their ‘essence, core inner nature, Self’.[194][note 16] According to Karl Brunnholzl “the earliest mahayana sutras that are based on and discuss the notion of tathāgatagarbha as the buddha potential that is innate in all sentient beings began to appear in written form in the late second and early third century.”[196] For some, the doctrine seems to conflict with the Buddhist anatta doctrine (non-Self), leading scholars to posit that the Tathāgatagarbha Sutras were written to promote Buddhism to non-Buddhists.[197][198] This can be seen in texts like the Laṅkāvatāra Sūtra, which state that Buddha-nature is taught to help those who have fear when they listen to the teaching of anatta.[199] Buddhist texts like the Ratnagotravibhāga clarify that the “Self” implied in Tathagatagarbha doctrine is actually “not-self“.[200][201] Various interpretations of the concept have been advanced by Buddhist thinkers throughout the history of Buddhist thought and most attempt to avoid anything like the Hindu Atman doctrine.[citation needed]

These Indian Buddhist ideas, in various synthetic ways, form the basis of subsequent Mahāyāna philosophy in Tibetan Buddhism and East Asian Buddhism.[citation needed]

Paths to liberation

Main article: Buddhist paths to liberation

The Bodhipakkhiyādhammā are seven lists of qualities or factors that promote spiritual awakening (bodhi). Each list is a short summary of the Buddhist path, and the seven lists substantially overlap. The best-known list in the West is the Noble Eightfold Path, but a wide variety of paths and models of progress have been used and described in the different Buddhist traditions. However, they generally share basic practices such as sila (ethics), samadhi (meditation, dhyana) and prajña (wisdom), which are known as the three trainings. An important additional practice is a kind and compassionate attitude toward every living being and the world. Devotion is also important in some Buddhist traditions, and in the Tibetan traditions visualisations of deities and mandalas are important. The value of textual study is regarded differently in the various Buddhist traditions. It is central to Theravada and highly important to Tibetan Buddhism, while the Zen tradition takes an ambiguous stance.

An important guiding principle of Buddhist practice is the Middle Way (madhyamapratipad). It was a part of Buddha’s first sermon, where he presented the Noble Eightfold Path that was a ‘middle way’ between the extremes of asceticism and hedonistic sense pleasures.[202][203] In Buddhism, states Harvey, the doctrine of “dependent arising” (conditioned arising, pratītyasamutpāda) to explain rebirth is viewed as the ‘middle way’ between the doctrines that a being has a “permanent soul” involved in rebirth (eternalism) and “death is final and there is no rebirth” (annihilationism).[204][205]

Paths to liberation in the early texts

A common presentation style of the path (mārga) to liberation in the Early Buddhist Texts is the “graduated talk”, in which the Buddha lays out a step-by-step training.[206]

In the early texts, numerous different sequences of the gradual path can be found.[207] One of the most important and widely used presentations among the various Buddhist schools is The Noble Eightfold Path, or “Eightfold Path of the Noble Ones” (Skt. ‘āryāṣṭāṅgamārga’). This can be found in various discourses, most famously in the Dhammacakkappavattana Sutta (The discourse on the turning of the Dharma wheel).

Other suttas such as the Tevijja Sutta, and the Cula-Hatthipadopama-sutta give a different outline of the path, though with many similar elements such as ethics and meditation.[207]

According to Rupert Gethin, the path to awakening is also frequently summarized by another a short formula: “abandoning the hindrances, practice of the four establishings of mindfulness, and development of the awakening factors”.[208]

Noble Eightfold Path

Main article: Noble Eightfold Path

The Eightfold Path consists of a set of eight interconnected factors or conditions, that when developed together, lead to the cessation of dukkha.[209] These eight factors are: Right View (or Right Understanding), Right Intention (or Right Thought), Right Speech, Right Action, Right Livelihood, Right Effort, Right Mindfulness, and Right Concentration.

This Eightfold Path is the fourth of the Four Noble Truths and asserts the path to the cessation of dukkha (suffering, pain, unsatisfactoriness).[210][211] The path teaches that the way of the enlightened ones stopped their craving, clinging and karmic accumulations, and thus ended their endless cycles of rebirth and suffering.[212][213][214]

The Noble Eightfold Path is grouped into three basic divisions, as follows:[215][216][217]

| Division | Eightfold factor | Sanskrit, Pali | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wisdom (Sanskrit: prajñā, Pāli: paññā) | 1. Right view | samyag dṛṣṭi, sammā ditthi | The belief that there is an afterlife and not everything ends with death, that Buddha taught and followed a successful path to nirvana;[215] according to Peter Harvey, the right view is held in Buddhism as a belief in the Buddhist principles of karma and rebirth, and the importance of the Four Noble Truths and the True Realities.[218] |

| 2. Right intention | samyag saṃkalpa, sammā saṅkappa | Giving up home and adopting the life of a religious mendicant in order to follow the path;[215] this concept, states Harvey, aims at peaceful renunciation, into an environment of non-sensuality, non-ill-will (to lovingkindness), away from cruelty (to compassion).[218] | |

| Moral virtues[216] (Sanskrit: śīla, Pāli: sīla) | 3. Right speech | samyag vāc, sammā vāca | No lying, no rude speech, no telling one person what another says about him, speaking that which leads to salvation.[215] |

| 4. Right action | samyag karman, sammā kammanta | No killing or injuring, no taking what is not given; no sexual acts in monastic pursuit,[215] for lay Buddhists no sensual misconduct such as sexual involvement with someone married, or with an unmarried woman protected by her parents or relatives.[219][220][221] | |

| 5. Right livelihood | samyag ājīvana, sammā ājīva | For monks, beg to feed, only possessing what is essential to sustain life.[222] For lay Buddhists, the canonical texts state right livelihood as abstaining from wrong livelihood, explained as not becoming a source or means of suffering to sentient beings by cheating them, or harming or killing them in any way.[223][224] | |

| Meditation[216] (Sanskrit and Pāli: samādhi) | 6. Right effort | samyag vyāyāma, sammā vāyāma | Guard against sensual thoughts; this concept, states Harvey, aims at preventing unwholesome states that disrupt meditation.[225] |

| 7. Right mindfulness | samyag smṛti, sammā sati | Never be absent-minded, conscious of what one is doing; this, states Harvey, encourages mindfulness about impermanence of the body, feelings and mind, as well as to experience the five skandhas, the five hindrances, the four True Realities and seven factors of awakening.[225] | |

| 8. Right concentration | samyag samādhi, sammā samādhi | Correct meditation or concentration (dhyana), explained as the four jhānas.[215][226] |

Common practices

Hearing and learning the Dharma

In various suttas which present the graduated path taught by the Buddha, such as the Samaññaphala Sutta and the Cula-Hatthipadopama Sutta, the first step on the path is hearing the Buddha teach the Dharma. This then said to lead to the acquiring of confidence or faith in the Buddha’s teachings.[207]

Mahayana Buddhist teachers such as Yin Shun also state that hearing the Dharma and study of the Buddhist discourses is necessary “if one wants to learn and practice the Buddha Dharma.”[227] Likewise, in Indo-Tibetan Buddhism, the “Stages of the Path” (Lamrim) texts generally place the activity of listening to the Buddhist teachings as an important early practice.[228]

Refuge

Main article: Refuge (Buddhism)

Traditionally, the first step in most Buddhist schools requires taking of the “Three Refuges”, also called the Three Jewels (Sanskrit: triratna, Pali: tiratana) as the foundation of one’s religious practice.[229] This practice may have been influenced by the Brahmanical motif of the triple refuge, found in the Rigveda 9.97.47, Rigveda 6.46.9 and Chandogya Upanishad 2.22.3–4.[230] Tibetan Buddhism sometimes adds a fourth refuge, in the lama. The three refuges are believed by Buddhists to be protective and a form of reverence.[229]

The ancient formula which is repeated for taking refuge affirms that “I go to the Buddha as refuge, I go to the Dhamma as refuge, I go to the Sangha as refuge.”[231] Reciting the three refuges, according to Harvey, is considered not as a place to hide, rather a thought that “purifies, uplifts and strengthens the heart”.[177]

Śīla – Buddhist ethics

Main article: Buddhist ethics

Śīla (Sanskrit) or sīla (Pāli) is the concept of “moral virtues”, that is the second group and an integral part of the Noble Eightfold Path.[218] It generally consists of right speech, right action and right livelihood.[218]

One of the most basic forms of ethics in Buddhism is the taking of “precepts”. This includes the Five Precepts for laypeople, Eight or Ten Precepts for monastic life, as well as rules of Dhamma (Vinaya or Patimokkha) adopted by a monastery.[232][233]

Other important elements of Buddhist ethics include giving or charity (dāna), Mettā (Good-Will), Heedfulness (Appamada), ‘self-respect’ (Hri) and ‘regard for consequences’ (Apatrapya).

Precepts

Main article: Five precepts

Buddhist scriptures explain the five precepts (Pali: pañcasīla; Sanskrit: pañcaśīla) as the minimal standard of Buddhist morality.[219] It is the most important system of morality in Buddhism, together with the monastic rules.[234]

The five precepts are seen as a basic training applicable to all Buddhists. They are:[232][235][236]

- “I undertake the training-precept (sikkha-padam) to abstain from onslaught on breathing beings.” This includes ordering or causing someone else to kill. The Pali suttas also say one should not “approve of others killing” and that one should be “scrupulous, compassionate, trembling for the welfare of all living beings”.[237]

- “I undertake the training-precept to abstain from taking what is not given.” According to Harvey, this also covers fraud, cheating, forgery as well as “falsely denying that one is in debt to someone”.[238]

- “I undertake the training-precept to abstain from misconduct concerning sense-pleasures.” This generally refers to adultery, as well as rape and incest. It also applies to sex with those who are legally under the protection of a guardian. It is also interpreted in different ways in the varying Buddhist cultures.[239]

- “I undertake the training-precept to abstain from false speech.” According to Harvey this includes “any form of lying, deception or exaggeration…even non-verbal deception by gesture or other indication…or misleading statements.”[240] The precept is often also seen as including other forms of wrong speech such as “divisive speech, harsh, abusive, angry words, and even idle chatter”.[241]

- “I undertake the training-precept to abstain from alcoholic drink or drugs that are an opportunity for heedlessness.” According to Harvey, intoxication is seen as a way to mask rather than face the sufferings of life. It is seen as damaging to one’s mental clarity, mindfulness and ability to keep the other four precepts.[242]

Undertaking and upholding the five precepts is based on the principle of non-harming (Pāli and Sanskrit: ahiṃsa).[243] The Pali Canon recommends one to compare oneself with others, and on the basis of that, not to hurt others.[244] Compassion and a belief in karmic retribution form the foundation of the precepts.[245][246] Undertaking the five precepts is part of regular lay devotional practice, both at home and at the local temple.[247][248] However, the extent to which people keep them differs per region and time.[249][248] They are sometimes referred to as the śrāvakayāna precepts in the Mahāyāna tradition, contrasting them with the bodhisattva precepts.[250]

Vinaya

Main article: Vinaya

Vinaya is the specific code of conduct for a sangha of monks or nuns. It includes the Patimokkha, a set of 227 offences including 75 rules of decorum for monks, along with penalties for transgression, in the Theravadin tradition.[251] The precise content of the Vinaya Pitaka (scriptures on the Vinaya) differs in different schools and tradition, and different monasteries set their own standards on its implementation. The list of pattimokkha is recited every fortnight in a ritual gathering of all monks.[251] Buddhist text with vinaya rules for monasteries have been traced in all Buddhist traditions, with the oldest surviving being the ancient Chinese translations.[252]

Monastic communities in the Buddhist tradition cut normal social ties to family and community and live as “islands unto themselves”.[253] Within a monastic fraternity, a sangha has its own rules.[253] A monk abides by these institutionalised rules, and living life as the vinaya prescribes it is not merely a means, but very nearly the end in itself.[253] Transgressions by a monk on Sangha vinaya rules invites enforcement, which can include temporary or permanent expulsion.[254]

Restraint and renunciation

Another important practice taught by the Buddha is the restraint of the senses (indriyasamvara). In the various graduated paths, this is usually presented as a practice which is taught prior to formal sitting meditation, and which supports meditation by weakening sense desires that are a hindrance to meditation.[255] According to Anālayo, sense restraint is when one “guards the sense doors in order to prevent sense impressions from leading to desires and discontent”.[255] This is not an avoidance of sense impression, but a kind of mindful attention towards the sense impressions which does not dwell on their main features or signs (nimitta). This is said to prevent harmful influences from entering the mind.[256] This practice is said to give rise to an inner peace and happiness which forms a basis for concentration and insight.[256]

A related Buddhist virtue and practice is renunciation, or the intent for desirelessness (nekkhamma).[257] Generally, renunciation is the giving up of actions and desires that are seen as unwholesome on the path, such as lust for sensuality and worldly things.[258] Renunciation can be cultivated in different ways. The practice of giving for example, is one form of cultivating renunciation. Another one is the giving up of lay life and becoming a monastic (bhiksu or bhiksuni).[259] Practicing celibacy (whether for life as a monk, or temporarily) is also a form of renunciation.[260] Many Jataka stories focus on how the Buddha practiced renunciation in past lives.[261]

One way of cultivating renunciation taught by the Buddha is the contemplation (anupassana) of the “dangers” (or “negative consequences”) of sensual pleasure (kāmānaṃ ādīnava). As part of the graduated discourse, this contemplation is taught after the practice of giving and morality.[262]

Another related practice to renunciation and sense restraint taught by the Buddha is “restraint in eating” or moderation with food, which for monks generally means not eating after noon. Devout laypersons also follow this rule during special days of religious observance (uposatha).[263]

In different Buddhist traditions, other related practices which focus on fasting are followed.[citation needed]

Mindfulness and clear comprehension

The training of the faculty called “mindfulness” (Pali: sati, Sanskrit: smṛti, literally meaning “recollection, remembering”) is central in Buddhism. According to Analayo, mindfulness is a full awareness of the present moment which enhances and strengthens memory.[264] The Indian Buddhist philosopher Asanga defined mindfulness thus: “It is non-forgetting by the mind with regard to the object experienced. Its function is non-distraction.”[265] According to Rupert Gethin, sati is also “an awareness of things in relation to things, and hence an awareness of their relative value”.[266]

There are different practices and exercises for training mindfulness in the early discourses, such as the four Satipaṭṭhānas (Sanskrit: smṛtyupasthāna, “establishments of mindfulness”) and Ānāpānasati (Sanskrit: ānāpānasmṛti, “mindfulness of breathing”).

A closely related mental faculty, which is often mentioned side by side with mindfulness, is sampajañña (“clear comprehension”). This faculty is the ability to comprehend what one is doing and is happening in the mind, and whether it is being influenced by unwholesome states or wholesome ones.[267]

Meditation – Sama-amādhi and dhyāna

Main articles: Buddhist meditation, Samadhi, Samatha, and Rupajhana

A wide range of meditation practices has developed in the Buddhist traditions, but “meditation” primarily refers to the attainment of samādhi and the practice of dhyāna (Pali: jhāna). Samādhi is a calm, undistracted, unified and concentrated state of awareness. It is defined by Asanga as “one-pointedness of mind on the object to be investigated. Its function consists of giving a basis to knowledge (jñāna).”[265] Dhyāna is “state of perfect equanimity and awareness (upekkhā-sati-parisuddhi),” reached through focused mental training.[268]

The practice of dhyāna aids in maintaining a calm mind and avoiding disturbance of this calm mind by mindfulness of disturbing thoughts and feelings.[269][note 17]

Origins

The earliest evidence of yogis and their meditative tradition, states Karel Werner, is found in the Keśin hymn 10.136 of the Rigveda.[270] While evidence suggests meditation was practised in the centuries preceding the Buddha,[271] the meditative methodologies described in the Buddhist texts are some of the earliest among texts that have survived into the modern era.[272][273] These methodologies likely incorporate what existed before the Buddha as well as those first developed within Buddhism.[274][note 18]

There is no scholarly agreement on the origin and source of the practice of dhyāna. Some scholars, like Bronkhorst, see the four dhyānas as a Buddhist invention.[278] Alexander Wynne argues that the Buddha learned dhyāna from Brahmanical teachers.[279]

Whatever the case, the Buddha taught meditation with a new focus and interpretation, particularly through the four dhyānas methodology,[280] in which mindfulness is maintained.[281][282] Further, the focus of meditation and the underlying theory of liberation guiding the meditation has been different in Buddhism.[271][283][284] For example, states Bronkhorst, the verse 4.4.23 of the Brihadaranyaka Upanishad with its “become calm, subdued, quiet, patiently enduring, concentrated, one sees soul in oneself” is most probably a meditative state.[285] The Buddhist discussion of meditation is without the concept of soul and the discussion criticises both the ascetic meditation of Jainism and the “real self, soul” meditation of Hinduism.[286]

The formless attainments

Often grouped into the jhāna-scheme are four other meditative states, referred to in the early texts as arupa samāpattis (formless attainments). These are also referred to in commentarial literature as immaterial/formless jhānas (arūpajhānas). The first formless attainment is a place or realm of infinite space (ākāsānañcāyatana) without form or colour or shape. The second is termed the realm of infinite consciousness (viññāṇañcāyatana); the third is the realm of nothingness (ākiñcaññāyatana), while the fourth is the realm of “neither perception nor non-perception”.[287] The four rupa-jhānas in Buddhist practice leads to rebirth in successfully better rupa Brahma heavenly realms, while arupa-jhānas leads into arupa heavens.[288][289]

Meditation and insight

See also: Meditation and insight and Yoga

In the Pali canon, the Buddha outlines two meditative qualities which are mutually supportive: samatha (Pāli; Sanskrit: śamatha; “calm”) and vipassanā (Sanskrit: vipaśyanā, insight).[290] The Buddha compares these mental qualities to a “swift pair of messengers” who together help deliver the message of nibbana (SN 35.245).[291]

The various Buddhist traditions generally see Buddhist meditation as being divided into those two main types.[292][293] Samatha is also called “calming meditation”, and focuses on stilling and concentrating the mind i.e. developing samadhi and the four dhyānas. According to Damien Keown, vipassanā meanwhile, focuses on “the generation of penetrating and critical insight (paññā)”.[294]

There are numerous doctrinal positions and disagreements within the different Buddhist traditions regarding these qualities or forms of meditation. For example, in the Pali Four Ways to Arahantship Sutta (AN 4.170), it is said that one can develop calm and then insight, or insight and then calm, or both at the same time.[295] Meanwhile, in Vasubandhu’s Abhidharmakośakārikā, vipaśyanā is said to be practiced once one has reached samadhi by cultivating the four foundations of mindfulness (smṛtyupasthānas).[296]

Beginning with comments by La Vallee Poussin, a series of scholars have argued that these two meditation types reflect a tension between two different ancient Buddhist traditions regarding the use of dhyāna, one which focused on insight based practice and the other which focused purely on dhyāna.[297][298] However, other scholars such as Analayo and Rupert Gethin have disagreed with this “two paths” thesis, instead seeing both of these practices as complementary.[298][299]

The Brahma-vihara

Main article: Brahmavihara

The four immeasurables or four abodes, also called Brahma-viharas, are virtues or directions for meditation in Buddhist traditions, which helps a person be reborn in the heavenly (Brahma) realm.[300][301][302] These are traditionally believed to be a characteristic of the deity Brahma and the heavenly abode he resides in.[303]

The four Brahma-vihara are:

- Loving-kindness (Pāli: mettā, Sanskrit: maitrī) is active good will towards all;[301][304]

- Compassion (Pāli and Sanskrit: karuṇā) results from metta; it is identifying the suffering of others as one’s own;[301][304]

- Empathetic joy (Pāli and Sanskrit: muditā): is the feeling of joy because others are happy, even if one did not contribute to it; it is a form of sympathetic joy;[304]

- Equanimity (Pāli: upekkhā, Sanskrit: upekṣā): is even-mindedness and serenity, treating everyone impartially.[301][304]

Tantra, visualization and the subtle body

See also: Tibetan Tantric Practice and Vajrayana § Tantra_techniques

Some Buddhist traditions, especially those associated with Tantric Buddhism (also known as Vajrayana and Secret Mantra) use images and symbols of deities and Buddhas in meditation. This is generally done by mentally visualizing a Buddha image (or some other mental image, like a symbol, a mandala, a syllable, etc.), and using that image to cultivate calm and insight. One may also visualize and identify oneself with the imagined deity.[305][306] While visualization practices have been particularly popular in Vajrayana, they may also found in Mahayana and Theravada traditions.[307]

In Tibetan Buddhism, unique tantric techniques which include visualization (but also mantra recitation, mandalas, and other elements) are considered to be much more effective than non-tantric meditations and they are one of the most popular meditation methods.[308] The methods of Unsurpassable Yoga Tantra, (anuttarayogatantra) are in turn seen as the highest and most advanced. Anuttarayoga practice is divided into two stages, the Generation Stage and the Completion Stage. In the Generation Stage, one meditates on emptiness and visualizes oneself as a deity as well as visualizing its mandala. The focus is on developing clear appearance and divine pride (the understanding that oneself and the deity are one).[309] This method is also known as deity yoga (devata yoga). There are numerous meditation deities (yidam) used, each with a mandala, a circular symbolic map used in meditation.[310]

Insight and knowledge

Main articles: Prajñā, Bodhi, Kenshō, Satori, Subitism, and Vipassana

Prajñā (Sanskrit) or paññā (Pāli) is wisdom, or knowledge of the true nature of existence. Another term which is associated with prajñā and sometimes is equivalent to it is vipassanā (Pāli) or vipaśyanā (Sanskrit), which is often translated as “insight”. In Buddhist texts, the faculty of insight is often said to be cultivated through the four establishments of mindfulness.[311] In the early texts, Paññā is included as one of the “five faculties” (indriya) which are commonly listed as important spiritual elements to be cultivated (see for example: AN I 16). Paññā along with samadhi, is also listed as one of the “trainings in the higher states of mind” (adhicittasikkha).[311]

The Buddhist tradition regards ignorance (avidyā), a fundamental ignorance, misunderstanding or mis-perception of the nature of reality, as one of the basic causes of dukkha and samsara. Overcoming this ignorance is part of the path to awakening. This overcoming includes the contemplation of impermanence and the non-self nature of reality,[312][313] and this develops dispassion for the objects of clinging, and liberates a being from dukkha and saṃsāra.[314][315][316]

Prajñā is important in all Buddhist traditions. It is variously described as wisdom regarding the impermanent and not-self nature of dharmas (phenomena), the functioning of karma and rebirth, and knowledge of dependent origination.[317] Likewise, vipaśyanā is described in a similar way, such as in the Paṭisambhidāmagga, where it is said to be the contemplation of things as impermanent, unsatisfactory and not-self.[318]

Devotion

Main article: Buddhist devotion

Most forms of Buddhism “consider saddhā (Sanskrit: śraddhā), ‘trustful confidence’ or ‘faith’, as a quality which must be balanced by wisdom, and as a preparation for, or accompaniment of, meditation.”[319] Because of this devotion (Sanskrit: bhakti; Pali: bhatti) is an important part of the practice of most Buddhists.[320] Devotional practices include ritual prayer, prostration, offerings, pilgrimage, and chanting.[321] Buddhist devotion is usually focused on some object, image or location that is seen as holy or spiritually influential. Examples of objects of devotion include paintings or statues of Buddhas and bodhisattvas, stupas, and bodhi trees.[322] Public group chanting for devotional and ceremonial is common to all Buddhist traditions and goes back to ancient India where chanting aided in the memorization of the orally transmitted teachings.[323] Rosaries called malas are used in all Buddhist traditions to count repeated chanting of common formulas or mantras. Chanting is thus a type of devotional group meditation which leads to tranquility and communicates the Buddhist teachings.[324]

Vegetarianism and animal ethics

Main article: Buddhist vegetarianism

Based on the Indian principle of ahimsa (non-harming), the Buddha’s ethics strongly condemn the harming of all sentient beings, including all animals. He thus condemned the animal sacrifice of the Brahmins as well hunting, and killing animals for food.[325] However, early Buddhist texts depict the Buddha as allowing monastics to eat meat. This seems to be because monastics begged for their food and thus were supposed to accept whatever food was offered to them.[326] This was tempered by the rule that meat had to be “three times clean”: “they had not seen, had not heard, and had no reason to suspect that the animal had been killed so that the meat could be given to them”.[327] Also, while the Buddha did not explicitly promote vegetarianism in his discourses, he did state that gaining one’s livelihood from the meat trade was unethical.[328] In contrast to this, various Mahayana sutras and texts like the Mahaparinirvana sutra, Surangama sutra and the Lankavatara sutra state that the Buddha promoted vegetarianism out of compassion.[329] Indian Mahayana thinkers like Shantideva promoted the avoidance of meat.[330] Throughout history, the issue of whether Buddhists should be vegetarian has remained a much debated topic and there is a variety of opinions on this issue among modern Buddhists.

Texts

Main article: Buddhist texts

Buddhism, like all Indian religions, was initially an oral tradition in ancient times.[331] The Buddha’s words, the early doctrines, concepts, and their traditional interpretations were orally transmitted from one generation to the next. The earliest oral texts were transmitted in Middle Indo-Aryan languages called Prakrits, such as Pali, through the use of communal recitation and other mnemonic techniques.[332] The first Buddhist canonical texts were likely written down in Sri Lanka, about 400 years after the Buddha died.[331] The texts were part of the Tripitakas, and many versions appeared thereafter claiming to be the words of the Buddha. Scholarly Buddhist commentary texts, with named authors, appeared in India, around the 2nd century CE.[331] These texts were written in Pali or Sanskrit, sometimes regional languages, as palm-leaf manuscripts, birch bark, painted scrolls, carved into temple walls, and later on paper.[331]

Unlike what the Bible is to Christianity and the Quran is to Islam, but like all major ancient Indian religions, there is no consensus among the different Buddhist traditions as to what constitutes the scriptures or a common canon in Buddhism.[331] The general belief among Buddhists is that the canonical corpus is vast.[333][334][335] This corpus includes the ancient Sutras organised into Nikayas or Agamas, itself the part of three basket of texts called the Tripitakas.[336] Each Buddhist tradition has its own collection of texts, much of which is translation of ancient Pali and Sanskrit Buddhist texts of India. The Chinese Buddhist canon, for example, includes 2184 texts in 55 volumes, while the Tibetan canon comprises 1108 texts – all claimed to have been spoken by the Buddha – and another 3461 texts composed by Indian scholars revered in the Tibetan tradition.[337] The Buddhist textual history is vast; over 40,000 manuscripts – mostly Buddhist, some non-Buddhist – were discovered in 1900 in the Dunhuang Chinese cave alone.[337]

Early texts

Main article: Early Buddhist Texts

The Early Buddhist Texts refers to the literature which is considered by modern scholars to be the earliest Buddhist material. The first four Pali Nikayas, and the corresponding Chinese Āgamas are generally considered to be among the earliest material.[338][339][340] Apart from these, there are also fragmentary collections of EBT materials in other languages such as Sanskrit, Khotanese, Tibetan and Gāndhārī. The modern study of early Buddhism often relies on comparative scholarship using these various early Buddhist sources to identify parallel texts and common doctrinal content.[341] One feature of these early texts are literary structures which reflect oral transmission, such as widespread repetition.[342]

The Tripitakas

Main articles: Tripiṭaka and Pali Canon

After the development of the different early Buddhist schools, these schools began to develop their own textual collections, which were termed Tripiṭakas (Triple Baskets).[343]

Many early Tripiṭakas, like the Pāli Tipitaka, were divided into three sections: Vinaya Pitaka (focuses on monastic rule), Sutta Pitaka (Buddhist discourses) and Abhidhamma Pitaka, which contain expositions and commentaries on the doctrine. The Pāli Tipitaka (also known as the Pali Canon) of the Theravada School constitutes the only complete collection of Buddhist texts in an Indic language which has survived until today.[344] However, many Sutras, Vinayas and Abhidharma works from other schools survive in Chinese translation, as part of the Chinese Buddhist Canon. According to some sources, some early schools of Buddhism had five or seven pitakas.[345]

Mahāyāna texts

Main article: Mahayana sutras

The Mahāyāna sūtras are a very broad genre of Buddhist scriptures that the Mahāyāna Buddhist tradition holds are original teachings of the Buddha. Modern historians generally hold that the first of these texts were composed probably around the 1st century BCE or 1st century CE.[346][347][348] In Mahāyāna, these texts are generally given greater authority than the early Āgamas and Abhidharma literature, which are called “Śrāvakayāna” or “Hinayana” to distinguish them from Mahāyāna sūtras.[349] Mahāyāna traditions mainly see these different classes of texts as being designed for different types of persons, with different levels of spiritual understanding. The Mahāyāna sūtras are mainly seen as being for those of “greater” capacity.[350][better source needed] Mahāyāna also has a very large literature of philosophical and exegetical texts. These are often called śāstra (treatises) or vrittis (commentaries). Some of this literature was also written in verse form (karikās), the most famous of which is the Mūlamadhyamika-karikā (Root Verses on the Middle Way) by Nagarjuna, the foundational text of the Madhyamika school.

Tantric texts

Main article: Tantras (Buddhism)

During the Gupta Empire, a new class of Buddhist sacred literature began to develop, which are called the Tantras.[351] By the 8th century, the tantric tradition was very influential in India and beyond. Besides drawing on a Mahāyāna Buddhist framework, these texts also borrowed deities and material from other Indian religious traditions, such as the Śaiva and Pancharatra traditions, local god/goddess cults, and local spirit worship (such as yaksha or nāga spirits).[352][353]

Some features of these texts include the widespread use of mantras, meditation on the subtle body, worship of fierce deities, and antinomian and transgressive practices such as ingesting alcohol and performing sexual rituals.[354][355][356]

History

Main article: History of Buddhism

For a chronological guide, see Timeline of Buddhism.

Historical roots

Historically, the roots of Buddhism lie in the religious thought of Iron Age India around the middle of the first millennium BCE.[357] This was a period of great intellectual ferment and socio-cultural change known as the “Second urbanisation”, marked by the growth of towns and trade, the composition of the Upanishads and the historical emergence of the Śramaṇa traditions.[358][359][note 19]

New ideas developed both in the Vedic tradition in the form of the Upanishads, and outside of the Vedic tradition through the Śramaṇa movements.[362][363][364] The term Śramaṇa refers to several Indian religious movements parallel to but separate from the historical Vedic religion, including Buddhism, Jainism and others such as Ājīvika.[365]

Several Śramaṇa movements are known to have existed in India before the 6th century BCE (pre-Buddha, pre-Mahavira), and these influenced both the āstika and nāstika traditions of Indian philosophy.[366] According to Martin Wilshire, the Śramaṇa tradition evolved in India over two phases, namely Paccekabuddha and Savaka phases, the former being the tradition of individual ascetic and the latter of disciples, and that Buddhism and Jainism ultimately emerged from these.[367] Brahmanical and non-Brahmanical ascetic groups shared and used several similar ideas,[368] but the Śramaṇa traditions also drew upon already established Brahmanical concepts and philosophical roots, states Wiltshire, to formulate their own doctrines.[366][369] Brahmanical motifs can be found in the oldest Buddhist texts, using them to introduce and explain Buddhist ideas.[370] For example, prior to Buddhist developments, the Brahmanical tradition internalised and variously reinterpreted the three Vedic sacrificial fires as concepts such as Truth, Rite, Tranquility or Restraint.[371] Buddhist texts also refer to the three Vedic sacrificial fires, reinterpreting and explaining them as ethical conduct.[372]

The Śramaṇa religions challenged and broke with the Brahmanic tradition on core assumptions such as Atman (soul, self), Brahman, the nature of afterlife, and they rejected the authority of the Vedas and Upanishads.[373][374][375] Buddhism was one among several Indian religions that did so.[375]

Early Buddhist positions in the Theravada tradition had not established any deities, but were epistemologically cautious rather than directly atheist. Later Buddhist traditions were more influenced by the critique of deities within Hinduism and therefore more committed to a strongly atheist stance. These developments were historic and epistemological as documented in verses from Śāntideva‘s Bodhicaryāvatāra, and supplemented by reference to suttas and jātakas from the Pali canon.[376]

Indian Buddhism

Main article: History of Buddhism in India

The history of Indian Buddhism may be divided into five periods:[377] Early Buddhism (occasionally called pre-sectarian Buddhism), Nikaya Buddhism or Sectarian Buddhism (the period of the early Buddhist schools), Early Mahayana Buddhism, Late Mahayana, and the era of Vajrayana or the “Tantric Age”.

Pre-sectarian Buddhism

Main article: Pre-sectarian Buddhism

According to Lambert Schmithausen Pre-sectarian Buddhism is “the canonical period prior to the development of different schools with their different positions”.[378]

The early Buddhist Texts include the four principal Pali Nikāyas [note 20] (and their parallel Agamas found in the Chinese canon) together with the main body of monastic rules, which survive in the various versions of the patimokkha.[379][380][381] However, these texts were revised over time, and it is unclear what constitutes the earliest layer of Buddhist teachings. One method to obtain information on the oldest core of Buddhism is to compare the oldest extant versions of the Theravadin Pāli Canon and other texts.[note 21] The reliability of the early sources, and the possibility to draw out a core of oldest teachings, is a matter of dispute.[384] According to Vetter, inconsistencies remain, and other methods must be applied to resolve those inconsistencies.[382][note 22]

According to Schmithausen, three positions held by scholars of Buddhism can be distinguished:[388]

- “Stress on the fundamental homogeneity and substantial authenticity of at least a considerable part of the Nikayic materials”. Proponents of this position include A. K. Warder[note 23] and Richard Gombrich.[390][note 24]

- “Scepticism with regard to the possibility of retrieving the doctrine of earliest Buddhism”. Ronald Davidson is a proponent of this position.[note 25]

- “Cautious optimism in this respect”. Proponents of this position include J.W. de Jong,[392][note 26] Johannes Bronkhorst[note 27] and Donald Lopez.[note 28]

The Core teachings

According to Mitchell, certain basic teachings appear in many places throughout the early texts, which has led most scholars to conclude that Gautama Buddha must have taught something similar to the Four Noble Truths, the Noble Eightfold Path, Nirvana, the three marks of existence, the five aggregates, dependent origination, karma and rebirth.[394]

According to N. Ross Reat, all of these doctrines are shared by the Theravada Pali texts and the Mahasamghika school’s Śālistamba Sūtra.[395] A recent study by Bhikkhu Analayo concludes that the Theravada Majjhima Nikaya and Sarvastivada Madhyama Agama contain mostly the same major doctrines.[396] Richard Salomon, in his study of the Gandharan texts (which are the earliest manuscripts containing early discourses), has confirmed that their teachings are “consistent with non-Mahayana Buddhism, which survives today in the Theravada school of Sri Lanka and Southeast Asia, but which in ancient times was represented by eighteen separate schools.”[397]

However, some scholars argue that critical analysis reveals discrepancies among the various doctrines found in these early texts, which point to alternative possibilities for early Buddhism.[398][399][400] The authenticity of certain teachings and doctrines have been questioned. For example, some scholars think that karma was not central to the teaching of the historical Buddha, while other disagree with this position.[401][402] Likewise, there is scholarly disagreement on whether insight was seen as liberating in early Buddhism or whether it was a later addition to the practice of the four jhānas.[385][403][404] Scholars such as Bronkhorst also think that the four noble truths may not have been formulated in earliest Buddhism, and did not serve in earliest Buddhism as a description of “liberating insight”.[405] According to Vetter, the description of the Buddhist path may initially have been as simple as the term “the middle way”.[140] In time, this short description was elaborated, resulting in the description of the eightfold path.[140]

Ashokan Era and the early schools

Main articles: Early Buddhist schools, Buddhist councils, and Theravada

According to numerous Buddhist scriptures, soon after the parinirvāṇa (from Sanskrit: “highest extinguishment”) of Gautama Buddha, the first Buddhist council was held to collectively recite the teachings to ensure that no errors occurred in oral transmission. Many modern scholars question the historicity of this event.[406] However, Richard Gombrich states that the monastic assembly recitations of the Buddha’s teaching likely began during Buddha’s lifetime, and they served a similar role of codifying the teachings.[407]

The so called Second Buddhist council resulted in the first schism in the Sangha. Modern scholars believe that this was probably caused when a group of reformists called Sthaviras (“elders”) sought to modify the Vinaya (monastic rule), and this caused a split with the conservatives who rejected this change, they were called Mahāsāṃghikas.[408][409] While most scholars accept that this happened at some point, there is no agreement on the dating, especially if it dates to before or after the reign of Ashoka.[410]

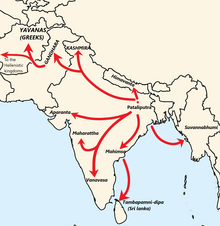

Buddhism may have spread only slowly throughout India until the time of the Mauryan emperor Ashoka (304–232 BCE), who was a public supporter of the religion. The support of Aśoka and his descendants led to the construction of more stūpas (such as at Sanchi and Bharhut), temples (such as the Mahabodhi Temple) and to its spread throughout the Maurya Empire and into neighbouring lands such as Central Asia and to the island of Sri Lanka.

During and after the Mauryan period (322–180 BCE), the Sthavira community gave rise to several schools, one of which was the Theravada school which tended to congregate in the south and another which was the Sarvāstivāda school, which was mainly in north India. Likewise, the Mahāsāṃghika groups also eventually split into different Sanghas. Originally, these schisms were caused by disputes over monastic disciplinary codes of various fraternities, but eventually, by about 100 CE if not earlier, schisms were being caused by doctrinal disagreements too.[411]

Following (or leading up to) the schisms, each Saṅgha started to accumulate their own version of Tripiṭaka (triple basket of texts).[67][412] In their Tripiṭaka, each school included the Suttas of the Buddha, a Vinaya basket (disciplinary code) and some schools also added an Abhidharma basket which were texts on detailed scholastic classification, summary and interpretation of the Suttas.[67][413] The doctrine details in the Abhidharmas of various Buddhist schools differ significantly, and these were composed starting about the third century BCE and through the 1st millennium CE.[414][415][416]

Post-Ashokan expansion

Main article: Silk Road transmission of Buddhism

According to the edicts of Aśoka, the Mauryan emperor sent emissaries to various countries west of India to spread “Dharma”, particularly in eastern provinces of the neighbouring Seleucid Empire, and even farther to Hellenistic kingdoms of the Mediterranean. It is a matter of disagreement among scholars whether or not these emissaries were accompanied by Buddhist missionaries.[417]

In central and west Asia, Buddhist influence grew, through Greek-speaking Buddhist monarchs and ancient Asian trade routes, a phenomenon known as Greco-Buddhism. An example of this is evidenced in Chinese and Pali Buddhist records, such as Milindapanha and the Greco-Buddhist art of Gandhāra. The Milindapanha describes a conversation between a Buddhist monk and the 2nd-century BCE Greek king Menander, after which Menander abdicates and himself goes into monastic life in the pursuit of nirvana.[418][419] Some scholars have questioned the Milindapanha version, expressing doubts whether Menander was Buddhist or just favourably disposed to Buddhist monks.[420]

The Kushan empire (30–375 CE) came to control the Silk Road trade through Central and South Asia, which brought them to interact with Gandharan Buddhism and the Buddhist institutions of these regions. The Kushans patronised Buddhism throughout their lands, and many Buddhist centres were built or renovated (the Sarvastivada school was particularly favored), especially by Emperor Kanishka (128–151 CE).[421][422] Kushan support helped Buddhism to expand into a world religion through their trade routes.[423] Buddhism spread to Khotan, the Tarim Basin, and China, eventually to other parts of the far east.[422] Some of the earliest written documents of the Buddhist faith are the Gandharan Buddhist texts, dating from about the 1st century CE, and connected to the Dharmaguptaka school.[424][425][426]

The Islamic conquest of the Iranian Plateau in the 7th-century, followed by the Muslim conquests of Afghanistan and the later establishment of the Ghaznavid kingdom with Islam as the state religion in Central Asia between the 10th- and 12th-century led to the decline and disappearance of Buddhism from most of these regions.[427]

Mahāyāna Buddhism

Main article: Mahāyāna

The origins of Mahāyāna (“Great Vehicle”) Buddhism are not well understood and there are various competing theories about how and where this movement arose. Theories include the idea that it began as various groups venerating certain texts or that it arose as a strict forest ascetic movement.[428]

The first Mahāyāna works were written sometime between the 1st century BCE and the 2nd century CE.[347][428] Much of the early extant evidence for the origins of Mahāyāna comes from early Chinese translations of Mahāyāna texts, mainly those of Lokakṣema. (2nd century CE).[note 29] Some scholars have traditionally considered the earliest Mahāyāna sūtras to include the first versions of the Prajnaparamita series, along with texts concerning Akṣobhya, which were probably composed in the 1st century BCE in the south of India.[430][note 30]

There is no evidence that Mahāyāna ever referred to a separate formal school or sect of Buddhism, with a separate monastic code (Vinaya), but rather that it existed as a certain set of ideals, and later doctrines, for bodhisattvas.[432][433] Records written by Chinese monks visiting India indicate that both Mahāyāna and non-Mahāyāna monks could be found in the same monasteries, with the difference that Mahāyāna monks worshipped figures of Bodhisattvas, while non-Mahayana monks did not.[434]

Mahāyāna initially seems to have remained a small minority movement that was in tension with other Buddhist groups, struggling for wider acceptance.[435] However, during the fifth and sixth centuries CE, there seems to have been a rapid growth of Mahāyāna Buddhism, which is shown by a large increase in epigraphic and manuscript evidence in this period. However, it still remained a minority in comparison to other Buddhist schools.[436]

Mahāyāna Buddhist institutions continued to grow in influence during the following centuries, with large monastic university complexes such as Nalanda (established by the 5th-century CE Gupta emperor, Kumaragupta I) and Vikramashila (established under Dharmapala c. 783 to 820) becoming quite powerful and influential. During this period of Late Mahāyāna, four major types of thought developed: Mādhyamaka, Yogācāra, Buddha-nature (Tathāgatagarbha), and the epistemological tradition of Dignaga and Dharmakirti.[437] According to Dan Lusthaus, Mādhyamaka and Yogācāra have a great deal in common, and the commonality stems from early Buddhism.[438]

Late Indian Buddhism and Tantra

Main article: Vajrayana

During the Gupta period (4th–6th centuries) and the empire of Harṣavardana (c. 590–647 CE), Buddhism continued to be influential in India, and large Buddhist learning institutions such as Nalanda and Valabahi Universities were at their peak.[439] Buddhism also flourished under the support of the Pāla Empire (8th–12th centuries). Under the Guptas and Palas, Tantric Buddhism or Vajrayana developed and rose to prominence. It promoted new practices such as the use of mantras, dharanis, mudras, mandalas and the visualization of deities and Buddhas and developed a new class of literature, the Buddhist Tantras. This new esoteric form of Buddhism can be traced back to groups of wandering yogi magicians called mahasiddhas.[440][441]