CARPENTERS/ BALLADS

Main menu

Personal tools

Contents

hide

- (Top)

- HistoryToggle History subsection

- Musical styleToggle Musical style subsection

- Promotion and touring

- Public image

- Legacy and influence

- Biographies

- Discography

- ReferencesToggle References subsection

- External links

The Carpenters

195 languages

Tools

Appearancehide

Text

- SmallStandardLarge

Width

- StandardWide

Color (beta)

- AutomaticLightDark

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

This article is about the American pop duo. For their third studio album, see Carpenters (album). For other uses, see Carpenters (disambiguation).

| Carpenters | |

|---|---|

| Karen and Richard Carpenter in 1974 | |

| Background information | |

| Also known as | The Carpenters |

| Origin | Downey, California, United States |

| Genres | Popsoft rock[1][2] |

| Years active | 1965–1983 |

| Labels | A&M |

| Past members | Karen CarpenterRichard Carpenter |

| Website | carpentersofficial.com richardandkarencarpenter.com |

The Carpenters[a] were an American vocal and instrumental duo consisting of siblings Karen (1950–1983) and Richard Carpenter (born 1946). They produced a distinctive soft musical style, combining Karen’s contralto vocals with Richard’s harmonizing, arranging, and composition. During their 14-year career, the Carpenters recorded 10 albums along with many singles and several television specials.

The siblings were born in New Haven, Connecticut, and moved to Downey, California, in 1963. Richard took piano lessons as a child, progressing to California State University, Long Beach, while Karen learned the drums. They first performed together as a duo in 1965 and formed the jazz-oriented Richard Carpenter Trio along with Wesley Jacobs, then formed the middle-of-the-road band Spectrum. Subsequently the two signed as Carpenters to A&M Records in 1969, they achieved major success the following year with the hit singles “(They Long to Be) Close to You” and “We’ve Only Just Begun“. The duo’s brand of melodic pop produced a record-breaking run of hit recordings on the American Top 40 and Adult Contemporary charts, and they became leading sellers in the soft rock, easy listening, and adult contemporary music genres. They had three number-one singles and five number-two singles on the Billboard Hot 100 and 15 number-one hits on the Adult Contemporary chart, in addition to 12 top-10 singles.

The duo toured continually during the 1970s, which put them under increased strain; Richard took a year off in 1979 after he had become addicted to Quaalude, while Karen suffered from anorexia nervosa. Their joint career ended in 1983 when Karen died from heart failure brought on by complications of anorexia. Her death triggered widespread coverage and research into eating disorders. Their music continues to attract critical acclaim and commercial success. They have sold more than 100 million records worldwide, making them among of the best-selling music artists of all time.

History

[edit]

Pre-Carpenters

[edit]

Childhood

[edit]

The Carpenter siblings were both born at Grace–New Haven Hospital in New Haven, Connecticut, to Harold Bertram Carpenter (1908–1988) and Agnes Reuwer (née Tatum, 1915–1996). Harold was born in Wuzhou, China, moving to Britain in 1917, and the US in 1921, while Agnes was born and grew up in Baltimore, Maryland. They married on April 9, 1935; their first child, Richard Lynn, was born on October 15, 1946, while Karen Anne followed on March 2, 1950.[4] Richard was a quiet child who spent most of his time at home listening to Rachmaninoff, Tchaikovsky, Red Nichols and Spike Jones, and playing the piano.[5] Karen was friendly and outgoing; she liked to play sports, including softball with the neighborhood kids, but still spent a lot of time listening to music. She enjoyed dancing and began ballet and tap classes at the age of four. Karen and Richard were close, and shared a common interest in music. In particular, they became fans of Les Paul and Mary Ford, whose music featured multiple overdubbed voices and instruments.[6] Richard began piano lessons aged eight, but quickly grew frustrated with the formal direction of the lessons and quit after a year. From the age of 11, he had begun to teach himself to play by ear, and resumed studying with a different teacher. He took a greater interest in playing this time, and would frequently practice at home. By 14, he was interested in performing professionally, and started lessons at Yale School of Music.[7]

In June 1963, the Carpenter family moved to the Los Angeles suburb of Downey hoping that it would mean better musical opportunities for Richard.[8][9][10] He was asked to be the organist for weddings and services at the local Methodist church; instead of playing traditional hymns, he would sometimes rearrange contemporary Beatles songs in a “church” style.[11] In late 1964, Richard enrolled at California State College at Long Beach where he met future songwriting partner John Bettis, Wesley Jacobs, a friend who played the bass and tuba for the Richard Carpenter Trio, and choral director Frank Pooler, who co-wrote the Christmas standard “Merry Christmas Darling” in 1966.[12]

That same year, Karen enrolled at Downey High School, where she found she had a knack for playing the drums.[13] She had initially tried playing the glockenspiel, but had been inspired by her friend Frankie Chavez, who had been drumming since he was three. She became enthusiastic about the drums, and began to learn complex pieces, such as Dave Brubeck‘s “Take Five“.[14] Chavez persuaded her parents to buy a Ludwig drum kit in late 1964, and she began lessons with local jazz players, including how to read concert music. She quickly replaced the entry-level kit with a large Ludwig set that was a similar set-up to Brubeck’s drummer, Joe Morello. Richard and Karen gave their first public performance together in 1965, as part of the pit band for a local production of Guys and Dolls.[15][16]

The Richard Carpenter Trio and Spectrum

[edit]

By 1965, Karen had been practicing the drums for a year, and Richard was refining his piano techniques under Pooler’s instruction. Late that year, Richard teamed up with Jacobs, who played tuba and stand-up bass. With Karen drumming, the three formed the jazz-oriented Richard Carpenter Trio.[12] Richard led the band and wrote all the arrangements, and they began to rehearse daily.[17] He bought a tape recorder, and began to make recordings of the group. Originally, neither Karen nor Richard sang; Richard’s friend Dan Friberg occasionally filled in on trumpet, along with guest vocalist Margaret Shanor.[18]

Karen subsequently became more confident in singing, and began to take lessons with Frank Pooler. He taught her a mixture of classical and pop singing, but realized she most enjoyed performing Richard’s new material. Pooler later said, “Karen was a born pop singer”.[19] In early 1966, Karen tagged along at a late-night session in the garage studio of Los Angeles bassist Joe Osborn, and joined future Carpenters collaborator and lyricist John Bettis at a demo session where Richard was to accompany Friberg.[20][21] Asked to sing, she performed for Osborn, who was immediately impressed with her vocal abilities. He signed Karen to his label, Magic Lamp Records, and Richard to his publishing arm, Lightup Music.[22] The label put out a single featuring two of Richard’s compositions, “Looking for Love” and “I’ll Be Yours”. As well as Karen’s vocals, the track was backed by the Richard Carpenter Trio. The single was not a commercial success due to a lack of promotion, and the label folded the next year.[23]

In mid-1966, the Richard Carpenter Trio entered the Hollywood Bowl annual Battle of the Bands competition. They played an instrumental version of “The Girl from Ipanema” and their own piece, “Iced Tea”. They won the competition on June 24 and were signed by RCA Records.[24] They recorded songs such as the Beatles’ “Every Little Thing” and Frank Sinatra‘s “Strangers in the Night“. A committee reviewed their recordings and chose not to produce them, so the trio were released from RCA.[25][b]

Karen graduated from high school in early 1967, and was awarded the John Philip Sousa Band award.[26] She subsequently joined Richard at Long Beach State as a music major.[27] Osborn let Karen and Richard continue to use his studio to record demo tapes.[28] As they had unlimited studio time, Richard decided to experiment with overdubbing his and Karen’s voices in order to create a large choral sound.[29]

In 1967, Jacobs left to study classical music and join the Detroit Symphony Orchestra, and the Richard Carpenter Trio disbanded.[30] Richard and Bettis then were hired as musicians at a refreshment shop at Disneyland‘s Main Street, U.S.A. They were expected to play turn of the 20th century songs in keeping with the shop’s theme. The shop’s patrons had other ideas; many requested the musicians to play current popular music. When the pair tried pleasing their customers and honoring the requests, they were fired by a Disneyland supervisor, Victor Guder, for being “too radical”.[31][32] Bettis and Richard were unhappy about their dismissal and wrote the song “Mr. Guder” about their former superior.[32]

Richard and Karen then teamed up with student musicians from Long Beach State to form the band Spectrum.[33] The group included Bettis on guitar, who began writing lyrics to Richard’s songs, guitarist Gary Sims, bassist Dan Woodhams, and vocalist Leslie “Toots” Johnston.[34] The group sent demos to various record labels around Los Angeles, with little success. Part of the problem was the group’s middle-of-the-road sound, which was different from the psychedelic rock popular in clubs.[28] Richard’s friend Ed Sulzer managed to book time at United Audio Recording Studio in Santa Ana, and the group recorded several original songs including “Candy” (which became “One Love” on the Carpenters’ self-titled 1971 album). Richard bought a Wurlitzer electric piano as an additional instrument to complement his acoustic piano onstage.[35] Spectrum performed regularly at the Whisky a Go Go nightclub in Los Angeles, including opening for Steppenwolf early in that group’s career.[36][37]

By 1968, Spectrum had disbanded, finding it difficult to get gigs as their music was not considered “danceable” by rock and roll standards.[38] Having enjoyed their multi-layer sound experiments at Osborn’s studio, Richard and Karen decided to formally become a duo, calling themselves Carpenters. Later in the year, the duo received an offer to be on the television program Your All-American College Show. Their performance on the program, playing a cover of “Dancing in the Street“, was their first television appearance, with new bassist Bill Sissoyev.[39] The program had a weekly winner with all weekly winners competing in semi-finals and finals at the end of 12 weeks. The finals featuring “The Dick Carpenter Trio” aired on August 31, 1968.[40] Karen also auditioned as a vocalist in Kenny Rogers and The First Edition, but was unsuccessful.[3] By this time, Sulzer had become the group’s manager, while the duo continued to record demos with Osborn, one of which was sent to A&M Records via a friend of Sulzer’s. At the same time, the duo were asked to audition for a Ford Motor Company advertising campaign, which included $50,000 each and a brand new Ford automobile.[41] The group accepted the offer, but quickly withdrew it after receiving a formal offer from A&M. Label owner Herb Alpert was intrigued by Karen’s voice, later saying “It touched me … I felt like it was time”. On meeting the duo, Alpert said “Let’s hope we can have some hits!”[42]

As the Carpenters

[edit]

Offering (Ticket to Ride)

[edit]

Richard and Karen Carpenter signed to A&M Records on April 22, 1969.[42] Since Karen was 19 and underage, her parents had to co-sign.[43] The duo had decided to sign as “Carpenters”, without the definite article, which was influenced by names such as Buffalo Springfield or Jefferson Airplane, which they considered “hip”.[3]

When the Carpenters signed to A&M Records, they were given free rein in the studio to create an album in their own style.[42] The label recommended that Jack Daugherty should produce it, though those present have since suggested that Richard was the de facto producer. Most of the album’s material had already been written for and performed with Spectrum; “Your Wonderful Parade” and “All I Can Do” both came from demos recorded with Osborn. Richard rearranged the Beatles’ “Ticket to Ride” in a melancholic ballad style.[44] Osborn played bass on the album (and remained their regular studio bassist throughout their career). Karen also played bass on “All of My Life” and “Eve”, after being taught the relevant parts by Osborn.[45][c] The album, entitled Offering, was released on October 9, 1969, to a positive critical reception; one review in Billboard said “With radio programming support, Carpenters should have a big hit on their hands.”[45]

“Ticket to Ride” was released as a single on November 5, and became a minor hit for the Carpenters, peaking at No. 54 on the Billboard Hot 100 and the Top 20 of the Adult Contemporary chart.[46][47] The album sold only 18,000 copies on its initial run, at a loss for A&M, but after the Carpenters’ subsequent breakthrough the album was repackaged and reissued internationally under the name Ticket to Ride and sold 250,000 copies.[48]

Close to You

[edit]

Despite the poor showing of Offering, A&M retained the Carpenters and decided they should record a hit single instead. In December 1969, they met Burt Bacharach, who was impressed by their work and invited the duo to open for him at a charity concert, which should include them performing a medley of Bacharach / Hal David songs.[d] Herb Alpert asked Richard to re-work a Bacharach/David song “(They Long to Be) Close to You“, which had first been recorded in 1963 by Richard Chamberlain, and Dionne Warwick the following year. Richard Carpenter decided the song would work as a standalone piece, and wrote an arrangement from scratch without being influenced by any earlier recordings.[50] The duo struggled on an early recording attempt, and for the second session, Alpert suggested that seasoned session player Hal Blaine play drums instead of Karen, although Blaine stated that Karen approved of his involvement.[51] Larry Knechtel was tried out as a session pianist, but was replaced by Richard for the final take.[52] The Carpenters’ version was released as a single in March 1970.[53] It entered the charts at No. 56, the highest debut of the week ending June 20.[54] It reached No. 1 on July 25 and stayed there for the next four weeks.[55]

Their next hit was a song Richard had seen in a television commercial for Crocker National Bank, “We’ve Only Just Begun“, written by Paul Williams and Roger Nichols.[56] Three months after “Close to You” reached No. 1, the Carpenters’ version of “We’ve Only Just Begun” reached No. 2 on the Billboard Hot 100, becoming the first of their eventual five No. 2 hits (it was unable to get past “I’ll Be There” by The Jackson 5 and “I Think I Love You” by The Partridge Family during its four-week stay). The song became the first hit single for Williams and Nichols, who think the Carpenters’ version is definitive.[57]

“Close to You” and “We’ve Only Just Begun” became RIAA certified gold singles and were featured on the bestselling album Close to You, which placed No. 175 on Rolling Stone‘s 500 Greatest Albums of All Time list in 2003.[58] The album also included “Mr. Guder”, the song inspired by Disneyland supervisor Victor Guder, who had dismissed the young songwriters for playing popular music when they worked at the park.[59][32]

The Carpenters began touring, attempting to recruit Jacobs and former Spectrum members. Jacobs decided to continue with the Detroit Symphony, but Woodhams and Sims agreed to be part of the live band, which was completed with Doug Strawn and Bob Messenger. They rehearsed daily on the A&M soundstage in order to present a concert show that could compare with their records. As a result of their chart success, the group made several television appearances in 1970, including The Ed Sullivan Show.[60] The Carpenters also chose Sherwin Bash as their new manager around this time.[61] On Thanksgiving Day, 1970, the Carpenter family moved into a new $300,000 ($2,354,000 as of 2023) home near the San Gabriel River.[62][e]

The duo rounded out the year with the holiday release of “Merry Christmas, Darling”, which they had been playing for several years. The single scored high on the holiday charts and would repeatedly return to the holiday charts in subsequent years.[64] In 1978, Karen re-cut the vocal for their Christmas TV special, feeling she could give a more mature treatment to it; this remake also became a hit.[65]

Carpenters and A Song for You

[edit]

The Carpenters had a string of hit singles and albums through the early 1970s. Their 1971 song “For All We Know” was recorded the previous year by members of the pop group Bread for a wedding scene in the movie Lovers and Other Strangers. Richard saw the song’s potential for the Carpenters and recorded it in the autumn of 1970. The track became the duo’s third gold single, and later won an Oscar for “Best Original Song”.[66][67] On March 16, 1971, the duo received 2 Grammy Awards, winning for Best New Artist and Best Contemporary Performance by a Duo, Group or Chorus.[68]

The duo’s fourth gold single, “Rainy Days and Mondays“, became Williams’ and Nichols’ second major single with the Carpenters. The demo was written by Williams about his mother, which led to the line, “Talking to myself and feeling old”. Richard rearranged the song to include a saxophone solo, played by Bob Messenger. The single peaked at No. 2 on the Billboard Hot 100.[69]

“Superstar“, written by Bonnie Bramlett and Leon Russell, became the duo’s next hit. The song had originally appeared on Joe Cocker‘s 1970 album Mad Dogs & Englishmen, sung by Rita Coolidge. Karen was familiar with the album, but Richard first heard the song when it was covered by Bette Midler on The Tonight Show, and realized its potential as a Carpenters hit. The duo changed the line “I can hardly wait to sleep with you again” to “… to be with you again”, as they knew the former would not be played on Top 40 radio.[70] The single sold a million copies, attaining gold status, and became the Carpenters’ third No. 2 single on the Billboard Hot 100 (this time held off the top spot by Rod Stewart‘s “Maggie May” / “Reason to Believe“).[71][72] On May 14, 1971, the Carpenters performed a sell-out show at Carnegie Hall,[73] and they released their third album, Carpenters the same day.[74] It became one of their best sellers, earning RIAA certification for platinum four times,[75] and rising to No. 2 on Billboard‘s pop album chart for two weeks (behind Carole King’s Tapestry) with over a million pre-sales orders. The album won a Grammy Award, as well as receiving three nominations.[76] The A&M graphics department hired Craig Braun and Associates to design the cover.[77] “I recognized it to be a great logo as soon as I saw it”, says Richard.[77] The logo was used on every Carpenters album thereafter; Richard said it was done “to keep things consistent”.[77] The logo did not appear on the front cover of Passage but a small version appeared on the back cover.[77]

Shortly after the third album, the duo hosted a television series during the summer of 1971, called Make Your Own Kind of Music, which drew mixed reviews.[78] By mid-1971, the Carpenters were being criticized that their live shows had no focal point, as Karen was seated behind the drums. Richard and Bash tried to persuade her to sing out-front.[79] Karen resisted at first, but was eventually persuaded to front the popular numbers and ballads, and drum for more up-tempo numbers. Consequently, Jim Anthony was hired as a touring drummer.[80] Over time, Karen became more relaxed as a frontwoman and centerpiece of the band.[81]

“‘The Carpenters’ and ‘fuzz guitar solo’ are two phrases that do not exactly go hand in hand. But for one brief moment, the two coexisted merrily in the soft-rock universe.”[82]

Problems playing this file? See media help.

Later that year, Richard was watching a Bing Crosby movie, Rhythm on the River, in which Crosby played a country singer whose career was in decline and whose most famous song was “Goodbye to Love”. The song was never performed in the film, so Richard imagined what it might sound like and wrote down some initial lyrics. These were finished off by Bettis, and became “Goodbye to Love“.[81] For the arrangement, Richard suggested adding a fuzz guitar solo. He resisted suggestions to get an experienced session player in, and instead asked Tony Peluso, whose band Instant Joy had supported the Carpenters on an earlier tour. Peluso was a typical rock guitarist and did not read music, so Richard wrote out a chord chart for him to follow. Having been instructed to play the first five bars of the melody and then improvise, he recorded the solo in two takes. Bettis later described “Goodbye to Love” as his favorite single he has worked on in his career.[83] The single reached No. 7 in the Billboard Hot 100, and Peluso accepted an offer to tour with the Carpenters full-time.[84] Some did not appreciate the combination of a soft ballad and loud electric guitar, and sent hate mail to the Carpenters, but conversely they picked up new fans who appreciated the bridge between rock and pop.[83]

On April 25, 1972, the Carpenters visited the White House to meet presidential assistants James Cavanagh, Ken Cole and Ronald Zeigler. They returned on August 1 to meet President Richard Nixon and posed for photographs with him at the Oval Office.[85]

“Goodbye to Love” was featured on the Carpenters’ fourth album, A Song for You released on June 13, 1972. The title track, a cover of a song on Leon Russell’s debut album, was considered as a single, but rejected owing to its length. The album also included a Carole King song, “It’s Going To Take Some Time” and another Nichols / Williams original, “I Won’t Last a Day Without You“.[86] Another Carpenter / Bettis composition, “Top of the World“, was originally intended as just an album cut, but after Lynn Anderson scored a hit with the song in early 1973, the Carpenters opted to record their own single version. It was released in September and became the Carpenters’ second Billboard No. 1 hit, in December.[87]

Now & Then

[edit]

The Carpenters met the President again on April 30, 1973, when they performed a special concert at the White House, though the event was overshadowed by the resignation of the White House Chief of Staff, Bob Haldeman, and assistant John Ehrlichman over the Watergate scandal, which would ultimately also lead to Nixon’s resignation.[88]

Their next album, Now & Then, was named by the duo’s mother, Agnes. It contained Sesame Street’s signature song “Sing“, featuring the Jimmy Joice Children’s Choir, which was released as a single, reaching No. 3 on the Hot 100.[89][90] The album also included a Leon Russell composition, “This Masquerade“, and the ambitious “Yesterday Once More“, a side-long tribute to oldies radio which incorporated renditions of eight hit songs from previous decades into a faux oldies radio program.[91][92] The single version of the latter became their biggest hit in the United Kingdom, holding the No. 2 spot for two weeks,[93] and became the Carpenters’ biggest worldwide hit.[94]

In 1974, the Carpenters achieved a significant international hit with an up-tempo remake of Hank Williams’s “Jambalaya (On the Bayou)“.[95] While the song was not released as a single in the US, it reached the top 30 in Japan, No. 12 in the United Kingdom (as part of a double A-side with “Mr. Guder”[93]), and No. 3 in the Netherlands.[96] At Christmas that year, the duo released a jazz-influenced rendition of “Santa Claus Is Coming to Town” and appeared on Perry Como‘s Christmas show.[97][98]

The Singles: 1969–1973

[edit]

The Carpenters did not record a new album in 1974. They had been touring extensively and were exhausted; Richard later said, “there was simply no time to make one. Nor was I in the mood.”[99] Tensions had erupted in the family unit; Richard had started dating the group’s hairdresser but neither Agnes nor Karen took kindly to her and she ultimately ended the relationship and quit the band’s services. Agnes had always praised Richard’s musical talents, which Karen resented.[100] The duo ultimately moved out of their parents’ house; at first the siblings shared a home.[101][102] In May, the Carpenters undertook their first tour of Japan, playing to 85,000 fans. They later likened the scenes when they first touched down at Tokyo Airport to Beatlemania.[103]

During this period, the pair released just one single, “I Won’t Last a Day Without You” from A Song for You. The Carpenters finally decided to release their original two years after its original album release and some months after Maureen McGovern‘s 1973 cover.[104] In March 1974, the single version became the fifth and final selection from the album to chart in the Top 20, reaching No. 11 on the Hot 100 in May.[105]

In place of a new album, their first greatest hits package was released, featuring remixes of their singles, and newly recorded leads and bridges that allowed each side of the album to play through with no breaks. Richard later regretted this decision.[87][106] This compilation was entitled The Singles: 1969–1973, and topped the charts in the US for one week, on January 5, 1974. It also topped the UK chart for 17 weeks (non-consecutive) and became one of the bestselling albums of the decade, ultimately selling more than seven million copies in the US alone.[75]

Horizon

[edit]

In 1975, the Carpenters had a hit with a remake of the Marvelettes‘ chart-topping 1961 single, “Please Mr. Postman“. The song topped the Billboard Hot 100 in January and became the duo’s third and final No. 1 pop single.[97] It also earned Karen and Richard their record-setting twelfth million-selling gold single in the US.[75] The follow-up, a Carpenter / Bettis composition “Only Yesterday“, was the duo’s last Hot 100 top 10 hit, reaching No. 4.[107] The sound on the track was intended to emulate Phil Spector‘s famous Wall of Sound production technique.[108]

Both singles appeared on their 1975 LP Horizon, which also included covers of the Eagles‘ “Desperado” and Neil Sedaka‘s “Solitaire“, which became a moderate hit later that year. Horizon was certified gold after two weeks, but missed the top ten in the US, peaking at No. 13.[109] The album still had a positive critical reception.[108]

The Carpenters toured with Sedaka during 1975, but critics found the latter’s performances to be more professional and entertaining. Richard became particularly cross at how Sedaka was getting more attention, and ultimately fired him from the tour.[110][111] Karen struggled to cope with the demands of live shows, and a planned tour of the UK and Japan was canceled.[111][112][f] The duo began to produce music videos to promote their records; in early 1975, they filmed a performance of “Please Mr. Postman” at Disneyland and “Only Yesterday” at the Huntington Gardens.[106]

A Kind of Hush and Passage

[edit]

Their next album, A Kind of Hush, was released on June 11, 1976, and was certified gold.[75] However, it was the first Carpenters’ album not to become platinum-certified since Ticket to Ride seven years earlier. The duo had several hits that year, but by this time the public had become over-familiar with them, and sales fell.[114] Their biggest single that year was a cover of Herman’s Hermits‘ “There’s a Kind of Hush (All Over the World)“, which peaked at No. 12 on the Billboard Hot 100. “I Need to Be in Love” (Karen’s favorite song by the Carpenters)[115][116] charted at No. 25 on the Billboard Hot 100. However, it followed “There’s a Kind of Hush” to the top spot on the Adult Contemporary charts and became the duo’s 14th No. 1 Adult Contemporary hit, more than any other act in the history of the chart.[117]

The Carpenters’ First Television Special aired on December 8, 1976, and included guests John Denver and Victor Borge. It was the duo’s first headlining television variety show in the US. A follow-up special, The Carpenters at Christmas, aired on December 9, 1977, featuring Kristy McNichol.[118][119]

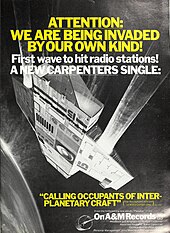

The 1977 album Passage marked an attempt to venture into other musical genres.[120] It featured an unlikely mix of jazz fusion (“B’wana She No Home”), calypso (“Man Smart, Woman Smarter”), and orchestrated balladry (“I Just Fall in Love Again“, “Two Sides”), and included the hits “All You Get from Love Is a Love Song” and “Calling Occupants of Interplanetary Craft“.[120] “Calling Occupants” was supported with the TV special Space Encounters, which aired May 17, 1978, with guest stars Suzanne Somers and John Davidson. Although the single release of “Calling Occupants” became a significant Top 10 hit in the UK and reached No. 1 in Ireland, it only peaked at number 32 on the Hot 100, and for the first time, a Carpenters album did not reach the gold threshold of 500,000 copies shipped in the US.[121] In early 1978, the duo had a surprise Top 10 country hit with the up-tempo, fiddle-sweetened “Sweet, Sweet Smile“, written by country-pop singer Juice Newton and her long-time musical partner Otha Young.[122]

The Singles: 1974–1978

[edit]

In place of a new album for 1978, a second compilation, The Singles: 1974–1978, was released in the UK where it reached No. 2 in the charts. In the US, their first Christmas album, Christmas Portrait, became a seasonal favorite, and was certified platinum. Richard later said that the album should have been released as Karen’s first solo album. It was shortly followed by the television special The Carpenters: A Christmas Portrait.[123] During the sessions, several non-Christmas songs were recorded such as “Where Do I Go from Here”, which was not released until after Karen’s death.[124]

Hiatus

[edit]

By 1978, Richard had become addicted to Quaalude, which he had been taking on prescription in increasing doses since the 1971 tours. On September 4, during an engagement at the MGM Grand in Las Vegas, he decided to quit touring, and the concerts there were curtailed.[125] On December 3, the Carpenters were scheduled to play at the Pacific Terrace Theatre, Long Beach Convention Center, which turned out to be the last live concert that Karen and Richard played together.[126] Richard refused to fly to the UK for an appearance on ITV‘s Bruce Forsyth’s Big Night, realizing he had a serious problem, so Karen performed without him and denied rumors that the duo were to split.[127]

Richard began treatment for his addiction at a facility in Topeka, Kansas, for six weeks in January 1979.[128] He decided to take the rest of the year off to relax and rehabilitate. Richard was now sure that Karen was battling with anorexia nervosa, but she denied it, saying she simply had colitis.[129] Karen did not want to take a break from singing nor seek professional medical help for her own condition, so she decided to pursue a solo album project with producer Phil Ramone in New York.[130][g] The choice of Ramone and more adult-oriented and disco / dance-tempo material represented an effort to retool her image.[132] Heatwave keyboardist and songwriter (and future Michael Jackson collaborator) Rod Temperton was asked by Ramone to help with songwriting and arranging, and Billy Joel‘s backing band were used for the album.[133] She decided not to record Temperton’s “Off the Wall” and “Rock with You“, which later became hits for Jackson.[134] The album was finished by early 1980, but drew a negative reception from A&M. Her mother Agnes did not like Karen working without Richard,[135] while Richard felt that Karen was not well enough to have worked on the album. The total cost of recording was $500,000 of which $400,000 came from the Carpenters’ own funds.[136] The album was not released and although the press announced it was canceled at Karen’s request, its rejection devastated her; she felt she had just wasted months of work.[137] It was finally issued in 1996, 13 years after Karen’s death.[138]

Made in America and Karen’s final days

[edit]

Following the cancellation of her solo album and her marriage to Tom Burris on August 31, 1980, Karen decided to record a new album with Richard, who had now recovered from his addiction and was ready to continue their career.[139] The Carpenters produced their final television special in 1980, called Music, Music, Music!, with guest stars Ella Fitzgerald and John Davidson.[140] Karen’s outfit for the show was designed by Bill Belew, who was nominated for an Emmy Award for best costume design. He had also designed her wedding dress.[141] Around the time of Music, Music, Music, Karen briefly returned to a healthier weight; in Spring 1980 she went on a retreat with Olivia Newton-John to the Golden Door health spa in San Diego and also worked with a Beverly Hills internist to improve her eating and restore some 20 pounds (9.1 kg) lost previously.[142][143][144]

On June 16, 1981, the Carpenters released what would become their final LP as a duo, Made in America.[145] The album sold around 200,000 copies and spawned the hit, “Touch Me When We’re Dancing“, which reached No. 16 on the Hot 100.[145] It also became their fifteenth and final number one Adult Contemporary hit. The album also produced three other singles, including “(Want You) Back in My Life Again“, “Those Good Old Dreams“, and a remake of the Motown hit “Beechwood 4-5789“. The singles fared well on the adult contemporary charts. “Beechwood 4-5789” was the last single by the Carpenters to be released in Karen’s lifetime, on her 32nd birthday.[146] The album concluded with “Because We Are in Love (The Wedding Song)”, referring to Karen’s marriage.[147] Promotion for the album included a whistle-stop tour of America, Brazil and Europe,[148] including an appearance on America’s Top Ten. The band mimed to the studio recordings for most performances, singing live for some European performances.[126][149][150][151]

After moving to New York City in January 1982,[152] Karen sought therapy for her eating disorder with psychotherapist Steven Levenkron.[153] In April, she briefly returned to Los Angeles for recording, including a Carpenter / Bettis tune “You’re Enough” and a Roger Nichols / Dean Pitchford song, “Now”. Richard noticed that while Karen’s interpretation of the songs was as strong as ever, he felt the timbre was weak owing to her poor health.[154] He was unimpressed with Levenkron’s treatment of Karen, considering it worthless.[155] In September 1982, Karen called Levenkron to say her heart was “beating funny” and she felt dizzy and confused.[156] Admitting herself into the hospital later that month, she was hooked up to an intravenous drip; she ended up gaining 30 pounds (14 kg) in eight weeks. On November 8, she left the hospital and despite pleas from family and friends, she announced that she was returning home to California and that she was cured.[157] Karen maintained this weight of 108 pounds (49 kg) thereafter, for the rest of her life.[158] Her last public appearance was on January 11, 1983, for a photo session celebrating 25 years of the Grammy Awards.[159][160]

Karen’s death

[edit]

On February 1, 1983, Karen and Richard met for dinner and discussed future plans for the Carpenters, including a return to touring.[161] On February 3, Karen visited her parents and discussed finalizing her divorce from Burris.[162] The following morning, her mother found her lying unresponsive on the floor of a walk-in closet, and she was rushed to the hospital.[163] After Richard and his parents spent 20 minutes in a waiting room, a doctor entered and told them Karen had died.[164] The autopsy stated that her death was caused by “emetine cardiotoxicity due to or as a consequence of anorexia nervosa.”[165] Under the anatomical summary, the first item was heart failure, followed by anorexia. The third finding was cachexia, which is extremely low weight and weakness and general body decline associated with chronic disease. Emetine cardiotoxicity implied that Karen abused ipecac syrup, although there was no other evidence to suggest that she did as her brother and family never found ipecac vials in her apartment, even after her death.[166]

Karen’s funeral was at the Downey United Methodist Church on February 8, 1983.[167] More than a thousand mourners attended, among them were her friends Dorothy Hamill, Olivia Newton-John, Petula Clark, Dionne Warwick and Herb Alpert.[168][169][170][171]

On October 12, 1983, the Carpenters received a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame. Richard, Harold, and Agnes Carpenter attended the inauguration, as did many fans.[172] Karen’s death brought media attention to anorexia nervosa and related conditions such as bulimia nervosa, which were little known about at the time.[173][174][175]

Post-Carpenters

[edit]

Following Karen’s death, Richard has continued to produce recordings of the duo’s music, including several albums of previously unreleased material and numerous compilations. The posthumous Voice of the Heart was released in late 1983 and included some tracks left off Made in America and earlier albums.[176] It peaked at No. 46 and was certified gold.[177] Two singles were released, “Make Believe It’s Your First Time“, a second version of a song Karen had recorded for her solo album, and “Your Baby Doesn’t Love You Anymore”.[177][178]

For the second Christmas season following Karen’s death, Richard constructed a new Carpenters’ Christmas album entitled An Old-Fashioned Christmas, using outtakes from Christmas Portrait and recording new material around it.[177] Richard released his first solo album, Time, in 1987, sharing vocals between himself, Dionne Warwick, and Dusty Springfield. The track “When Time Was All We Had” was a tribute to Karen.[176] The same year, Todd Haynes released the short film Superstar: The Karen Carpenter Story, which featured Barbie dolls playing the main cast. Richard objected to music being used in the film without his consent, and served an injunction in 1990 that prevented it from being shown.[179] On January 1, 1989, the television special The Karen Carpenter Story premiered on CBS, topping the ratings for that week.[180] It included the previously unreleased “You’re the One” and “Where Do I Go from Here” in its soundtrack, which were released on the album Lovelines later that year.[124]

Richard married his first cousin, Mary Rudolph, on May 19, 1984.[181] Together, they have four daughters and one son, and live in Thousand Oaks, California, where the couple are supporters of the arts.[182] In 2004, Richard and his wife pledged a $3 million gift to the Thousand Oaks Civic Arts Plaza Foundation in memory of Karen. Richard has actively supported the Carpenter Performing Arts Center at his alma mater, Long Beach State. He continues to make concert appearances, including fundraising efforts for the Carpenter Center.[183]

In 2007 and 2009, the current owners of the former Carpenter family home on Newville Avenue, Downey, obtained city permits to tear down the existing buildings to make room for newer and larger structures, despite protests from fans. In February 2008, the campaign was covered in the Los Angeles Times. At that time an adjacent house that had once served as the band’s headquarters and recording studio had already been demolished and the main house was on the verge of being demolished. The original house was featured on the cover of Now & Then and was where Karen had died. In the words of one fan, “this was our version of Graceland.”[184]

The Carpenters (both as a duo and separately) were among hundreds of artists whose material was destroyed in the 2008 Universal fire.[185] Richard told the Times he had been informed about the destruction of the master tapes by a Universal Music Enterprises employee while he was working on a reissue for the label, and only after he had made multiple, persistent inquiries into their whereabouts.[185]

Musical style

[edit]

Richard

[edit]

Richard Carpenter was the creative force behind the Carpenters’ sound. An accomplished keyboard player, composer and arranger, music critic Daniel Levitin called him “one of the most gifted arrangers to emerge in popular music.”[186][187] The duo’s smooth harmonies were not in step with contemporary music, which was dominated by heavy rock.[28] Instead, the Carpenters strove for a rich and melodic sound, along the same vein as the Beach Boys and the Mamas & the Papas, but with greater fullness and orchestration including frequent use of small string and horn sections and introspective lyrics centred around relationships.[2][188] Richard also admired the musicianship and arranging skills of Frank Zappa, and the two briefly met backstage at the Billboard Forum in 1975. He has credited Judd Conlon as a key influence on his vocal arranging.[77][189]

Many of Richard’s arrangements were classically influenced, featuring strings and occasional brass and woodwind, such as the Tijuana Brass-style couplets in the chorus of “Superstar”, which did not appear in the original. He later said “if you don’t have the right arrangement for that song, the singer’s going nowhere and neither is the song”.[190] As well as arranging all of the parts for musicians, he scored drum notation, showing where individual components of a kit were supposed to be played. He also scored bass lines that he knew Joe Osborn would enjoy playing and fit his style. Most Carpenters albums credit Ron Gorow, who sometimes took some of Richard’s arrangements worked out on piano, and wrote the actual sheet music notation onto paper.[187]

The chorus illustrates Karen’s lead vocal and Richard’s arranging skills, including himself on Wurlitzer electric piano, Joe Osborn‘s bass guitar, a string section, and brass couplets.

Problems playing this file? See media help.

Richard frequently played the Wurlitzer electric piano, which he purchased during his Spectrum days.[191] He also played the grand piano, Hammond organ, synthesizer and the harpsichord. In the studio, he dubbed the Wurlitzer over acoustic piano parts to thicken the sound. From the mid-1970s, he used Fender Rhodes pianos, and kept up to date with music technology.[192] While touring, he alternated between grand piano, Rhodes and Wurlitzer on stage, for different songs.[77]

Karen

[edit]

Karen did not possess a powerful singing voice, but close miking brought out many nuances in her performances.[108] Richard arranged their music to take advantage of this, though Karen had a three-octave vocal range.[193][194] Richard’s work with Karen was influenced by the music of Les Paul, whose overdubbing of the voice of wife and musical partner Mary Ford allowed her to be used as both the lead and harmony vocals.[6] By multi-tracking, Richard was able to use Karen and himself for the harmonies to back Karen’s lead. The overdubbed background harmonies were distinctive to the Carpenters, but it was the soulful, engaging sound of Karen’s lead voice that made them so recognizable.[29] Record executive Mike Curb said it was Karen’s voice that took the Carpenters above straight pop music into pop rock.[195] She was known as a “one take wonder” and could deliver a strong performance on the first attempt.[196]

Karen was an accomplished drummer, which was her original musical role, but she soon began to sing for the group too. Before 1974, Karen played the drums for a number of their songs, although some had Hal Blaine playing.[52] Blaine later reported that while Karen was a capable drummer he was brought in for studio work partly because Karen was accustomed to playing loudly for live audiences and thus was unfamiliar with the more subtle playing required in recording facilities of the era.[197] She considered herself a “drummer who sang”.[198] However, while Karen’s vocals soon became the centerpiece of the group’s performances, at 5 ft 4 in (1.63 m) tall, performing behind her drum kit made it difficult for audiences to see her and it was soon apparent to Richard and their manager that the audience wanted to see more of Karen. Although unwilling, she eventually agreed to sing the ballads standing up front, returning to her drums for the lesser known songs.[199]

As the group’s popularity increased, demand for Karen’s vocals at the expense of her drumming overshadowed her abilities and, gradually, she played the drums less; for A Kind of Hush, she played no drums at the sessions at all,[200] although she continued to sporadically drum in concert. From early 1976 onward, the tours featured a drum medley for Karen, and a piano solo number for Richard.[201] Karen made a final return to studio drumming for the track “When It’s Gone (It’s Just Gone)” on Made in America, albeit in tandem with Nashville session drummer Larrie Londin, and she also provided percussion in tandem with Paulinho da Costa on “Those Good Old Dreams”.[202] Karen used Ludwig drums, Zildjian cymbals, a Rogers foot pedal and hi-hat stand, 11A drumsticks and Remo drumheads.[77]

Promotion and touring

[edit]

Although the Carpenters’ greatest success was with record sales, most of their professional career was spent on the road. Albums took between four and five months to produce; the remainder of time would be spent at live concerts and television appearances. The duo played up to six one-night concerts back-to-back, which left them exhausted,[203] along with television shows including The Ed Sullivan Show, The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson, The Carol Burnett Show, The Mike Douglas Show and The Johnny Cash Show, as well as their own television specials.[204]

The Carpenters played numerous concerts from 1971 to 1975:[99]

| Year | Number of concerts | Number of TV appearances |

|---|---|---|

| 1971 | 145 concerts[99] | 10 TV appearances (as well as Make Your Own Kind of Music) |

| 1972 | 174 concerts[99] | 6 TV appearances |

| 1973 | 174 concerts[99] | 3 TV appearances |

| 1974 | 203 concerts[99] | 3 TV appearances |

| 1975 | 118 concerts + 46 postponed shows[99] | 1 TV appearance |

From the mid-1970s onwards, the Carpenters changed their stage show to allow Karen to have more presence and to interact with the audience, particularly between instrumental breaks.[205] However, extensive touring and lengthy recording sessions had begun to take their toll on the duo and contributed to their professional and personal difficulties during the latter half of the decade. Karen dieted obsessively and developed anorexia nervosa, which first manifested itself in 1975 when the duo was forced to cancel concert tours in the Philippines, UK and Japan.[206] Richard has said that he regrets the six- and seven-day work schedules of that period, adding that had he known then what he knows now, he would not have agreed to it, and was persuaded to do so by the belief that the Carpenters would not be financially stable without the touring.[207] Richard’s Quaalude addiction began to affect his performance in the late 1970s and led to the end of the duo’s live concert appearances in 1978.[125]

Despite numerous concert appearances, the Carpenters never released a live album in the US. Two such albums, Live in Japan (1974) and Live at the Palladium (1976) have been released in Japan and reissued on CD there. Richard has said he is not particularly interested in live albums.[77]

Public image

[edit]

The Carpenters’ popularity confounded critics. With their output focused on ballads and mid-tempo pop, the duo’s music was sometimes dismissed as being bland and saccharine. The recording industry, however, bestowed awards on the duo, who won three Grammy Awards during their career (Best New Artist, and Best Pop Performance by a Duo, Group, or Chorus, for “(They Long to Be) Close to You” in 1970;[208] and Best Pop Performance by a Duo or Group for Carpenters in 1971).[76] In 1974, the Carpenters were voted Favorite Pop/Rock Band, Duo, or Group at the first annual American Music Awards.[209]

From the start of their career, the Carpenters were coached by their management over handling interviews, and told to avoid saying anything controversial that would spoil their “clean cut” image.[210] A&M described the duo as “Real nice American kids – in 1971”.[211][212] While the Carpenters were not a rock band, they were reviewed by the rock press; in 1971, Rolling Stone‘s Lester Bangs described them as having “the most disconcerting collective stage presence of any band I have seen”. He also said that promotional photographs made them resemble “the cheery innocence of some years-past dream of California youth”, and they appeared to the public to be more conservative than they actually were.[h] The White House appearances only served to reinforce this image.[111][212][213]

Though the Carpenters had mass popular appeal and were recognized as being musically talented, people felt embarrassed and stigmatized about liking their records.[214] In later interviews, Richard stressed repeatedly how much he disliked the A&M executives for making their image “squeaky-clean”, and the critics for criticizing them for their image rather than their music.[215]

I got upset when this whole “squeaky clean” thing was tagged on to us. I never thought about standing for anything! They [the critics] took “Close to You” and said: “Aha, you see that number one? THAT’s for the people who believe in apple pie! THAT’s for people who believe in the American flag! THAT’s for the average middle-American person and his station wagon! The Carpenters stand for that, and I’m taking them to my bosom!” And boom, we got tagged with that label.[215]

After “Goodbye to Love” had been released, attitudes towards the duo changed slightly. Ken Barnes, writing in Phonograph said “It’s certainly less than revolutionary to admit you like the Carpenters these days – in ‘rock’ circles, if you recall, it formerly bordered on heresy. Everybody must be won over by now.”[198] Since then, the group’s “saccharine” image has softened and musicians have cited the Carpenters as a key influence.[216] In 1995, Rolling Stone‘s Sue Cummings wrote that the 1990s acceptance of the duo’s work was “a renewed ironic appreciation”, adding that listeners “had loved the veneer, then hated it, then found it even more compelling, on a second look, for the complexity in the places where the darkness cracked through”.[217]

Legacy and influence

[edit]

See also: List of awards and nominations received by the Carpenters

Rolling Stone ranked the Carpenters No. 10 on its list of the 20 Greatest Duos of All Time.[218] Karen Carpenter has been called one of the greatest female vocalists of all time by Rolling Stone[219] and National Public Radio.[9] Paul McCartney has said she was “the best female voice in the world: melodic, tuneful and distinctive”,[9] while Herb Alpert said she was “the type of singer who would sit in your lap and sing in your ear”.[220]

Shortly after Karen’s death, a film archivist discovered some rare footage of an early Carpenters’ television appearance. The archivist contacted Richard Carpenter and the two began viewing more footage which he had found. When the British division of A&M Records learned of the discoveries, they suggested the footage be turned into a video for home viewing. The finished piece, entitled “Yesterday Once More” is 55 minutes long and combines vintage and recent film clips. A&M Video and Richard intended “to create a video that played like an album”; all music was remixed from the masters and each selection was put into correct synchronization. The video was released in early 1985.[221]

Pop singer Michael Jackson was a fan of the duo. He cited the group as an early influence growing up.[222] Scott Weiland, lead singer of Stone Temple Pilots and Velvet Revolver, was a major fan of the group.[223] Karen Carpenter had a large influence on Weiland’s singing style.[224]

A critical re-evaluation of the Carpenters occurred during the 1990s and 2000s with the making of several documentaries such as Close to You: Remembering The Carpenters (US), The Sayonara (Japan), and Only Yesterday: The Carpenters Story (UK). Despite contentions that their sound was “too soft” to fall under the definition of rock and roll, major campaigns and petitions exist toward inducting the Carpenters into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.[195] Both “We’ve Only Just Begun” and “(They Long to Be) Close to You” have been honored with Grammy Hall of Fame awards for recordings of lasting quality or historical significance.[225] The Carpenters’ album and single sales total more than 90 million units making them one of the best-selling music artists of all time.[226]

Japanese singer Akiko Kobayashi has been influenced by Karen Carpenter, and she asked Richard to produce her 1988 album, City of Angels.[77] In 1990, the alternative rock band Sonic Youth recorded “Tunic (Song for Karen)” in recognition of her musical talents.[227] A tribute album, If I Were a Carpenter, by contemporary artists such as Sonic Youth, Bettie Serveert, Shonen Knife, Grant Lee Buffalo, Matthew Sweet, and The Cranberries, was released in 1994 and provided an alternative rock interpretation of Carpenters hits.[228] Richard Carpenter played keyboards for the Matthew Sweet cut “Let Me Be the One”.[229]

Guitarist Pat Metheny covered “Rainy Days and Mondays” for his album of cover versions of popular songs called What’s It All About, as a tribute to the band.[230] Modern entertainers such as the Bangles and Concrete Blonde have listed Karen Carpenter as an influence on their careers.[194] Brazilian pop duo Sandy & Junior was deemed the “Brazilian Carpenters” by the press[231] and recorded a cover version of “We’ve Only Just Begun” for their album Internacional (2002).[232] Indian musician M. M. Keeravani mentioned during his speech at the 2023 Academy Awards that he grew up listening to the Carpenters.[233]

Biographies

[edit]

In 2021, longtime Carpenters historian Chris May and Associated Press entertainment journalist Mike Cidoni Lennox published Carpenters: The Musical Legacy, based on interviews with Richard Carpenter.[234] It features rare photographs and newly revealed stories behind the making of the albums. Goldmine said the book “provided a candid and detailed look at much of what went into the Carpenters sound as well as Richard’s personal thoughts on the music business today.”[235]

Discography

[edit]

Main article: The Carpenters discography

See also: List of songs recorded by The Carpenters

The Carpenters released ten albums during their active career, of which five contained two or more top 20 hits on the Billboard Hot 100 (Close to You, Carpenters, A Song for You, Now & Then, and Horizon). Ten singles were certified gold by the RIAA, and twenty-two peaked in the top 10 on the Adult Contemporary chart.

- Offering (re-released as Ticket to Ride) (1969)

- Close to You (1970)

- Carpenters (1971)

- A Song for You (1972)

- Now & Then (1973)

- Horizon (1975)

- A Kind of Hush (1976)

- Passage (1977)

- Christmas Portrait (1978)

- Made in America (1981)

Posthumous releases

- Voice of the Heart (1983)

- An Old-Fashioned Christmas (1984)

- Lovelines (1989)

- As Time Goes By (2004)

References

[edit]

Explanatory notes

[edit]

- ^ Even though they are referred to as “The Carpenters”, their official name for authorized recordings and press material is simply “Carpenters”.[3]

- ^ In 1991, some 25 years later, a couple of these recordings were released as part of a From the Top boxed set of Carpenters material.[25]

- ^ Later Carpenters’ compilations feature Richard’s remixes of these songs, which include Osborn playing the bass.[45]

- ^ Bacharach invited the duo to open for him again at the Westbury Music Fair in 1970 as “Close to You” was beginning its climb on the music charts.[49]

- ^ By 1972, both Richard and Karen were millionaires. Their assets included two apartment complexes in Downey and two shopping centers.[63]

- ^ In an attempt to compensate UK record dealers for possible overstocking in anticipation of the now canceled tour, A&M Records issued a single of “Santa Claus Is Coming to Town” and “Merry Christmas Darling” for sale in the UK.[113]

- ^ In 1978, Karen was asked to sing on Gene Simmons‘ first solo album. She turned Simmons down; Helen Reddy and Donna Summer performed instead.[131]

- ^ Both Richard and Karen believed marijuana should be legal.[111]

Citations

[edit]

- ^ Talevski 2006, p. 70.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Simpson 2011, p. 61.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Schmidt 2010, p. 49.

- ^ Schmidt 2010, pp. 11–14, 297.

- ^ Schmidt 2010, p. 14.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Schmidt 2010, p. 16.

- ^ Schmidt 2010, pp. 18–19.

- ^ Coleman 1994, p. 47.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Samberg, Joel (February 4, 2013). “Remembering Karen Carpenter, 30 Years Later”. NPR. Archived from the original on August 31, 2015. Retrieved August 25, 2015.

- ^ Lott 2008, p. 226.

- ^ Schmidt 2010, pp. 22–23.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Coleman 1994, p. 53.

- ^ Coleman 1994, p. 51.

- ^ Schmidt 2010, pp. 24–25.

- ^ Coleman 1994, p. 52.

- ^ Schmidt 2010, p. 27.

- ^ Schmidt 2010, p. 28.

- ^ Schmidt 2010, p. 29.

- ^ Schmidt 2010, pp. 29–30.

- ^ Schmidt 2010, p. 32.

- ^ Coleman 1994, p. 58.

- ^ Schmidt 2010, p. 33.

- ^ Schmidt 2010, pp. 33–34.

- ^ Schmidt 2010, p. 34.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Coleman 1994, p. 59.

- ^ Schmidt 2010, p. 37.

- ^ Schmidt 2010, p. 41.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Schmidt 2010, p. 45.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Schmidt 2010, p. 48.

- ^ Schmidt 2010, pp. 42, 63.

- ^ Stanton 2003, p. 34.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c “North Augusta Student Meets The Carpenters”. Aiken Standard. December 5, 1972. p. 6. Archived from the original on October 11, 2017. Retrieved October 11, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Coleman 1994, p. 63.

- ^ Schmidt 2010, pp. 39, 43.

- ^ Schmidt 2010, pp. 45–46.

- ^ Schmidt 2010, p. 47.

- ^ Coleman 1994, p. 54.

- ^ Lieberman, Frank H. (November 17, 1973). “A Talented Brother and Sister Act Which Represents Clean, Wholesome Entertainment”. Billboard. p. C-10. ISSN 0006-2510. Archived from the original on October 5, 2017. Retrieved October 5, 2017.

- ^ “Dick Carpenter Trio”. Independent Press-Telegram. August 4, 1968. p. 176. Retrieved October 11, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ “Your All American College Show”. The Troy Record. August 31, 1968. p. 29. Retrieved October 11, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Schmidt 2010, p. 50.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Schmidt 2010, p. 53.

- ^ Coleman 1994, p. 76.

- ^ Schmidt 2010, p. 54.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Schmidt 2010, p. 55.

- ^ Schmidt 2010, p. 56.

- ^ Coleman 1994, p. 81.

- ^ Schmidt 2010, pp. 56, 69.

- ^ “The Burt Bacharach Orchestra The Carpenters”. Cash Box: 24. June 13, 1970. ISSN 0008-7289. Retrieved October 10, 2017.

- ^ Schmidt 2010, p. 57.

- ^ “Karen Carpenter 1950–1983”. Modern Drummer Magazine. Retrieved August 13, 2021.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Schmidt 2010, p. 58.

- ^ Schmidt 2010, p. 61.

- ^ Coleman 1994, p. 85.

- ^ “Carpenters – Chart history”. Billboard. Select “Hot 100” from the drop-down menu. Archived from the original on January 8, 2017. Retrieved October 4, 2017.

- ^ Schmidt 2010, p. 60.

- ^ Schmidt 2010, p. 66.

- ^ “Rolling Stone Magazine: 500 Greatest Albums”. Rolling Stone. November 18, 2003. Archived from the original on March 7, 2012. Retrieved March 8, 2009.

- ^ Schmidt 2010, pp. 66–67.

- ^ Schmidt 2010, p. 63.

- ^ Schmidt 2010, pp. 68–69.

- ^ Schmidt 2010, p. 70.

- ^ Small, Linda (May 6, 1972). “Carpenters Build Real Estate Empire”. Chillicothe Gazette. p. 17. Retrieved October 11, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Schmidt 2010, p. 180.

- ^ Schmidt 2010, pp. 180–81.

- ^ Schmidt 2010, p. 73.

- ^ Coleman 1994, p. 100.

- ^ Schmidt 2010, p. 74.

- ^ Schmidt 2010, pp. 75–76.

- ^ Schmidt 2010, pp. 77–78.

- ^ Schmidt 2010, p. 78.

- ^ Schmidt 2012, p. 49.

- ^ Schmidt 2010, p. 79.

- ^ Schmidt 2010, p. 80.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d “The Carpenters”. RIAA. Retrieved November 6, 2017.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Coleman 1994, p. 108.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f g h i Carpenter, Richard. “Fans Ask Archive”. Richard and Karen Carpenter (official website). Archived from the original on November 29, 2016. Retrieved October 2, 2017.

- ^ Schmidt 2010, p. 81.

- ^ Schmidt 2010, pp. 84–85.

- ^ Schmidt 2010, p. 86.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Schmidt 2010, p. 87.

- ^ Preto, Greg (May 31, 2012). “Goodbye to Love”. Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on October 5, 2017. Retrieved October 5, 2017.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Schmidt 2010, p. 88.

- ^ Coleman 1994, p. 127.

- ^ Schmidt 2010, p. 99.

- ^ Schmidt 2010, p. 90.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Schmidt 2010, p. 122.

- ^ Schmidt 2010, p. 100.

- ^ Schmidt 2010, p. 102.

- ^ Simpson 2011, p. 46.

- ^ Schmidt 2010, pp. 102–03.

- ^ Coleman 1994, p. 135.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “Carpenters | Artist”. Official Charts. Archived from the original on July 9, 2014. Retrieved April 25, 2014.

- ^ Schmidt 2010, p. 104.

- ^ Schmidt 2010, p. 103.

- ^ Steffen Hung. “Dutch charts portal”. dutchcharts.nl. Archived from the original on April 26, 2014. Retrieved April 25, 2014.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Schmidt 2010, p. 125.

- ^ “Christmasing with Perry Como”. The Journal News. December 15, 1974. p. 55. Archived from the original on October 7, 2017. Retrieved October 7, 2017.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f g Coleman 1994, p. 137.

- ^ Schmidt 2010, pp. 113–14.

- ^ Schmidt 2010, p. 115.

- ^ Lott 2008, p. 230.

- ^ Schmidt 2010, p. 123.

- ^ “Carpenters •• I Won’t Last A Day Without You”. Richard and Karen Carpenter (official website). June 4, 2008. Archived from the original on December 21, 2013. Retrieved April 25, 2014.

- ^ Whitburn, Joel (2004). The Billboard Book of Top 40 Hits: Eighth Edition. Record Research. p. 107.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “Carpenters Fans Ask-Richard Answers Revised Jan 2005”. Richard and Karen Carpenter (official website). June 4, 2008. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved August 25, 2015.

- ^ “Carpenters •• Only Yesterday”. Richard and Karen Carpenter (official website). June 4, 2008. Archived from the original on October 20, 2014. Retrieved April 25, 2014.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Schmidt 2010, p. 137.

- ^ Schmidt 2010, p. 136.

- ^ Schmidt 2010, p. 141.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d Windeler, Robert (August 2, 1976). “Brother & Sister Act”. People. Archived from the original on October 5, 2017. Retrieved October 5, 2017.

- ^ Schmidt 2010, p. 145.

- ^ “Carpenters Yule Single Out In UK”. Billboard. November 15, 1975. p. 65. ISSN 0006-2510. Archived from the original on October 11, 2017. Retrieved October 7, 2017.

- ^ Schmidt 2010, p. 170.

- ^ Schmidt 2010, p. 157.

- ^ Tobler 1998, p. 71.

- ^ Schmidt 2010, p. 169.

- ^ Schmidt 2010, p. 315.

- ^ Terrace 2013, p. 82.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Schmidt 2010, p. 172.

- ^ Coleman 1994, p. 231.

- ^ Schmidt 2010, p. 174.

- ^ Schmidt 2010, p. 182.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Schmidt 2010, p. 294.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Schmidt 2010, pp. 183–84.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Schmidt 2010, p. 185.

- ^ Schmidt 2010, pp. 186–87.

- ^ Schmidt 2010, p. 188.

- ^ Schmidt 2010, p. 189.

- ^ Schmidt 2010, pp. 192, 194.

- ^ Schmidt 2010, p. 191.

- ^ McCormick, Neil (February 4, 2016). “Karen Carpenter and the mystery of the missing album”. The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on September 22, 2017. Retrieved October 5, 2017.

- ^ Schmidt 2010, pp. 198, 200.

- ^ Schmidt 2010, p. 199.

- ^ Schmidt 2010, p. 207.

- ^ Schmidt 2010, pp. 208–09.

- ^ Schmidt 2010, pp. 212–13, 219.

- ^ Schmidt 2010, p. 311.

- ^ Schmidt 2010, pp. 227, 234.

- ^ Schmidt 2010, p. 224.

- ^ Schmidt 2010, p. 195.

- ^ Coleman 1994, p. 279.

- ^ Surratt, Paul and JoAnn Young (Executive Producers) (March 31, 1998). Close to You: Remembering the Carpenters (Videotape, DVD). MPI Home Video.

- ^ Schmidt 2010, p. 215.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Schmidt 2010, p. 236.

- ^ Schmidt 2010, pp. 236–37.

- ^ Schmidt 2010, p. 238.

- ^ “International Dateline”. Cash Box. January 16, 1982. p. 19. ISSN 0008-7289. Retrieved October 10, 2017.

- ^ “Carpenters – Touch Me When We’re Dancing. French TV 14.10.81”. YouTube. France. October 14, 1981. Archived from the original on May 24, 2020. Retrieved February 7, 2020.

- ^ “Carpenters zingen ‘Touch me when were dancing’ live bij Mies, 1981”. YouTube. The Netherlands. 1981. Archived from the original on October 30, 2021. Retrieved February 7, 2020.

- ^ “Carpenters – Top of the World – Live 1981”. YouTube. France: RoadOde.com. Retrieved February 7, 2020.

- ^ Schmidt, Randy (October 23, 2010). “Karen Carpenter: starved of love, by Randy Schmidt – Extract”. The Guardian. Retrieved December 14, 2018.

- ^ Schmidt 2010, p. 252.

- ^ Schmidt 2010, p. 254.

- ^ Schmidt 2010, p. 260.

- ^ Schmidt 2010, p. 263.

- ^ Schmidt 2010, p. 266.

- ^ Kornblum. “Karen Carpenter Autopsy Report” (PDF). Retrieved January 12, 2019.

A well-developed, thin 32 year old white female which measures 64 inches in length and weighs 108 pounds.

- ^ Schmidt 2010, p. 271.

- ^ “Industry Mourns Death Of Singer Karen Carpenter”. Cash Box. February 19, 1983. p. 30. ISSN 0008-7289. Retrieved October 10, 2017.

- ^ Schmidt 2010, p. 272.

- ^ Schmidt 2010, p. 273.

- ^ Schmidt 2010, p. 276.

- ^ Schmidt 2010, p. 278.

- ^ Schmidt 2010, p. 283.

- ^ Coleman 1994, pp. 21–24.

- ^ Schmidt 2010, p. 287.

- ^ Markel, Michelle (February 9, 1983). “1,000 Attend Rites for Karen Carpenter”. Los Angeles Times. p. 5. Archived from the original on September 24, 2017. Retrieved September 23, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Markel, Michelle (February 9, 1983). “1,000 Attend Rites for Karen Carpenter”. Los Angeles Times. p. 24. Archived from the original on September 24, 2017. Retrieved September 23, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Petrucelli 2009.

- ^ Schmidt 2012, p. 245.

- ^ Coleman 1994, p. 323.

- ^ Costin 2007, p. 2.

- ^ Zerbe 1995, pp. 249–50.

- ^ Latson, Jennifer (February 4, 2015). “How Karen Carpenter’s Death Changed the Way We Talk About Anorexia”. Time. Time-Life. Archived from the original on March 18, 2017. Retrieved October 5, 2017.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Schmidt 2010, p. 292.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Schmidt 2010, p. 309.

- ^ “Make Believe It’s Your First Time”. Richard and Karen Carpenter (official website). Archived from the original on March 14, 2016. Retrieved October 4, 2017.

- ^ Schmidt 2010, pp. 292–93.

- ^ Schmidt 2010, p. 293.

- ^ Hoerburger, Rob (October 6, 1996). “Karen Carpenter’s Second Life”. The New York Times. Archived from the original on July 1, 2015. Retrieved August 4, 2015.

[I]n 1984, the year after Karen died, he married his cousin Mary Rudolph and is now the father of four.

- ^ Schmidt 2010, pp. 297–98.

- ^ Schmidt 2010, p. 298.

- ^ “Fans love Carpenters but not carpenters”. Los Angeles Times. February 16, 2008. Retrieved April 25, 2014.[dead link]

- ^ Jump up to:a b Rosen, Jody (June 25, 2019). “Here Are Hundreds More Artists Whose Tapes Were Destroyed in the UMG Fire”. The New York Times. Retrieved June 28, 2019.

- ^ Levitin 1995, p. 199.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Levitin, Daniel (May 1995). “Arranging Master Class: Richard Carpenter”. Electronic Musician. Archived from the original on August 27, 2004. Retrieved December 27, 2007.

- ^ Schmidt 2010, pp. 43, 49.

- ^ “The Carpenters : Up From Downey”. Rolling Stone. July 4, 1974. Archived from the original on September 22, 2017. Retrieved September 30, 2017.

- ^ Levitin 1995, pp. 199, 202.

- ^ Schmidt 2010, p. 46.

- ^ Levitin 1995, p. 206.

- ^ Schmidt 2010, p. 30.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “What Do You Know About…Karen Carpenter?”. Modern Drummer. December 2013. Archived from the original on September 20, 2017. Retrieved September 19, 2017.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Schmidt 2010, p. 296.

- ^ “What Singers Can Learn From Karen Carpenter”. Voice Council Magazine. June 15, 2016. Archived from the original on October 6, 2017. Retrieved October 5, 2017.

- ^ “Jazz news: Hal Blaine on Karen Carpenter”. May 7, 2012.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Allen, Jeremy (August 2, 2017). “The Carpenters – 10 of the best”. The Guardian. Archived from the original on September 11, 2017. Retrieved October 2, 2017.

- ^ Schmidt 2010, p. 111.

- ^ Carpenter, Richard (1976). A Kind of Hush (Media notes). The Carpenters. A&M Records.

- ^ Schmidt 2010, p. 158.

- ^ Made In America (Media notes). A&M Records. 1981. SP-3723.

- ^ Schmidt 2010, p. 121.

- ^ Schmidt 2010, p. 314.

- ^ Schmidt 2010, p. 134.

- ^ Schmidt 2010, p. 144.

- ^ Schmidt 2010, p. 124.

- ^ Coleman 1994, p. 95.

- ^ “American Music Awards of 1974”. www.theamas.com. Archived from the original on October 11, 2017. Retrieved June 13, 2016.

- ^ Schmidt 2010, p. 105.

- ^ Schmidt 2010, p. 106.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Lott 2008, pp. 220–21.

- ^ Schmidt 2010, pp. 106–07.

- ^ Schmidt 2010, p. 108.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Coleman 1994, p. 109.

- ^ “The Carpenters Bio”. Rolling Stone. 2001. Archived from the original on October 5, 2017. Retrieved October 4, 2017.

- ^ Schmidt 2010, p. 295.

- ^ “20 Greatest Duos of All Time”. Rolling Stone. December 17, 2015. Retrieved September 5, 2020.

- ^ Hudak, Joseph (December 3, 2010). “Karen Carpenter – 100 Greatest Singers”. Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on September 8, 2015. Retrieved August 25, 2015.

- ^ Grein, Paul (February 19, 1983). “An Appreciation Carpenter’s Voice Lives On”. Billboard. p. 67. Archived from the original on October 6, 2017.

- ^ “A&M Video Releases Carpenters’ Video History”. Cash Box. May 11, 1985. p. 36. ISSN 0008-7289. Retrieved October 10, 2017.

- ^ Cadman, Chris (2015). Michael Jackson The Maestro The Definitive A–Z; Volume II – K–Z. Createspace Independent Publishing Platform. p. 25. ISBN 978-1-50762-440-1.

- ^ Gold, Jonathan (September 1993). “Steal this hook”. Spin. Vol. 9, no. 6. Camouflage Associates. pp. 56–57, 59–60, 137. ISSN 0886-3032.

- ^ DeLeo, Dean (October 19, 2021). “Stone Temple Pilots, Dean DeLeo interview – Trip the Witch + more”. Audio Ink Radio (Interview). Interviewed by Erickson, Anne.

- ^ “Grammy Hall of Fame Past Recipients”. Archived from the original on July 7, 2015. Retrieved April 25, 2014.

- ^ McCormick, Neil (February 4, 2016). “Karen Carpenter and the mystery of the missing album”. The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved November 28, 2016.

- ^ Fricke, David (August 9, 1990). “Sonic Youth: Goo”. Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on October 5, 2017. Retrieved October 4, 2017.

- ^ Cook, Stephen. “If I Were A Carpenter”. AllMusic. Retrieved November 6, 2017.

- ^ “A Carpenters alternative”. Statesman Journal. September 18, 1994. p. 36. Retrieved October 11, 2017 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ “Una de las voces más inusuales de la música popular”.

- ^ “Ribeirão recebe “Carpenters” Sandy & Junior”. Folha de S. Paulo (in Portuguese). October 20, 2000. Retrieved July 7, 2018.

- ^ Ferreira, Mauro (2002). “Sandy & Junior – Internacional”. IstoÉ Gente (in Portuguese). Archived from the original on August 31, 2017. Retrieved July 7, 2018.

- ^ “All the Asian actors and moments that stole the show at the Oscars”. NBC News. March 13, 2023. Retrieved March 14, 2023.

- ^ “Carpenters inspired Chris May’s music director career”.

- ^ “Carpenters: The Musical Legacy by Chris May and Mike Cidoni Lennox with Richard Carpenter”. December 23, 2021.

General sources

[edit]

- Coleman, Ray (1994). The Carpenters: The Untold Story. Harpercollins. ISBN 978-0-06-018345-5.

- Costin, Carolyn (2007). The Eating Disorder Sourcebook. McGraw-Hill Professional. ISBN 978-0-0718-1999-2.

- Levitin, Daniel (1995). “Arranging Master Class: Richard Carpenter”. Electronic Musician. Retrieved October 7, 2017.

- Lott, Eric (2008). “Perfect Is Dead: Karen Carpenter, Theodor Adorno, and the Radio; or, If Hooks Could Kill”. Criticism. 50 (2): 219–234. doi:10.1353/crt.0.0064. JSTOR 23128741. S2CID 192110065.

- Petrucelli, Alan W. (2009). Morbid Curiosity: The Disturbing Demises of the Famous and Infamous. Penguin. ISBN 978-1-1011-4049-9.

- Schmidt, Randy (2010). Little Girl Blue: The Life Of Karen Carpenter. Chicago Review Press. ISBN 978-1-556-52976-4.

- Schmidt, Randy, ed. (2012) [2002]. Yesterday Once More: The Carpenters Reader. Chicago Review Press. ISBN 978-1-613-74417-8.

- Simpson, Kim (2011). Early 70s Radio: The American Format Revolution. Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 978-1-44112-9-680.

- Stanton, Scott (2003). The Tombstone Tourist: Musicians. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-0-743-46330-0.

- Talevski, Nick (2006). Rock Obituaries – Knocking On Heaven’s Door. Omnibus Press. ISBN 978-1-8460-9091-2.

- Terrace, Vincent (2013). Television Specials: 5,336 Entertainment Programs, 1936–2012 (2nd ed.). McFarland. ISBN 978-1-476-61240-9.

- Tobler, John (1998). The Complete Guide to the Music of the Carpenters. Omnibus Press. ISBN 978-0-711-96312-2.

- Zerbe, Kathryn J. (1995). The Body Betrayed: A Deeper Understanding of Women, Eating Disorders, and Treatment. Gürze Books, LLC. ISBN 0-936077-23-9.

External links

[edit]

Wikimedia Commons has media related to The Carpenters.

- Official website

- Official Universal Music site

- “Carpenters” Archived July 4, 2020, at the Wayback Machine, The Richard and Karen Carpenter Performing Arts Center exhibit website

- Carpenters discography at Discogs

- The Carpenters at IMDb

- Society Music Theory – a musicologist’s discourse on the song “Superstar”

- Chris Walter – Pictures of the Carpenters in an official archive

- Carpenters Complete Recording Resource – discography and remix version resource

- Image of The Carpenters onstage at the Greek Theatre in Los Angeles, California, 1975. Los Angeles Times Photographic Archive (Collection 1429). UCLA Library Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library, University of California, Los Angeles.

| showvteUK best-selling albums (by year) (1970–1989) |

|---|

- The Carpenters

- American pop music duos

- Sibling musical duos

- Male–female musical duos

- American soft rock music groups

- Soft rock duos

- Ballad music groups

- A&M Records artists

- Grammy Award winners

- Musical groups established in 1969

- Musical groups disestablished in 1983

- Musical groups from Connecticut

- Musicians from New Haven, Connecticut

- Musical groups from California

- Musicians from Downey, California

- Mixed-gender bands