FRIENDS/BEACH BOYS

Main menu

Personal tools

Contents

hide

- (Top)

- Background

- Recording history

- Music and lyrics

- ContentToggle Content subsection

- Maharishi tour

- Sleeve design

- Release

- Critical receptionToggle Critical reception subsection

- Legacy

- Track listingToggle Track listing subsection

- Personnel

- Charts

- Notes

- References

- Bibliography

- External links

Friends (The Beach Boys album)

15 languages

Tools

Appearancehide

Text

- SmallStandardLarge

Width

- StandardWide

Color (beta)

- AutomaticLightDarkReport an issue with dark mode

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Friends | |

|---|---|

| Studio album by the Beach Boys | |

| Released | June 24, 1968 |

| Recorded | February – April 12, 1968 |

| Studio | Beach Boys and ID Sound, Los Angeles |

| Genre | Pop[1]lo-fi[2] |

| Length | 25:32 |

| Label | Capitol |

| Producer | The Beach Boys |

| The Beach Boys chronology | |

| Wild Honey (1967)Friends (1968)The Best of the Beach Boys Vol. 3 (1968) | |

| Singles from Friends | |

| “Friends” / “Little Bird“ Released: April 8, 1968 | |

Friends is the fourteenth studio album by the American rock band the Beach Boys, released on June 24, 1968, through Capitol Records. The album is characterized by its calm and peaceful atmosphere, which contrasted the prevailing music trends of the time, and by its brevity, with five of its 12 tracks running less than two minutes long. It sold poorly, peaking at number 126 on the Billboard charts, the group’s lowest U.S. chart performance to date, although it reached number 13 in the UK. Fans generally came to regard the album as one of the band’s finest.[3]

As with their two previous albums, Friends was recorded primarily at Brian Wilson’s home with a lo-fi production style. The album’s sessions lasted from February to April 1968 at a time when the band’s finances were rapidly diminishing. Despite crediting production to “the Beach Boys”, Wilson actively led the entire project, later referring to it as his second unofficial solo album (the first being 1966’s Pet Sounds). Some of the songs were inspired by the group’s recent involvement with Maharishi Mahesh Yogi and his Transcendental Meditation practice. It was the first album to feature songs from Dennis Wilson.

One single was issued from the album: “Friends“, a waltz that reached number 47 in the U.S. and number 25 in the UK. Its B-side was the Dennis co-write “Little Bird“. In May, the group scheduled a national tour with the Maharishi, but it was canceled after five shows due to low ticket sales and the Maharishi’s subsequent withdrawal. A standalone single, “Do It Again“, was released in July. It reached the U.S. top twenty, became their second number one hit in the UK, and was included in foreign pressings of Friends.

Friends received favorable reviews in the music press, but like their records since Smiley Smile (1967), the album’s simplicity divided critics and fans. Despite the failure of a collaborative tour with the Maharishi, the group remained supporters of him and his teachings. Dennis contributed more songs on later Beach Boys albums, eventually culminating in a solo record, 1977’s Pacific Ocean Blue. In 2018, session highlights, outtakes, and alternate takes were released for the compilation Wake the World: The Friends Sessions.

Background

[edit]

In September and December 1967, the Beach Boys released Smiley Smile and Wild Honey, respectively. Music fans were generally disappointed that the band twice failed to deliver on the hype surrounding their unreleased album Smile, which was advertised as the follow-up to the sophistication of Pet Sounds and “Good Vibrations” (both 1966). Instead, the group were making a deliberate choice to produce music that was simpler and less refined.[4] Commenting on Wild Honey, Mike Love said the band made a conscious decision to be “completely out of the mainstream for what was going on at that time, which was all hard rock/psychedelic music. [The album] just didn’t have anything to do with what was going on.”[5]

Although Wild Honey charted higher than Smiley Smile in the US, it was ultimately the group’s lowest-selling album to that point.[4] Apart from a two-week U.S. tour in November 1967,[6] the band was not performing live during this period, and their finances were rapidly diminishing.[7] That same month, the group stopped wearing their longtime striped-shirt stage uniforms in favor of matching white, polyester suits that were similar to a Las Vegas show band.[8][nb 1]

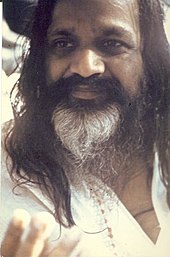

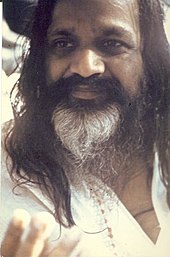

Dennis Wilson, Al Jardine, and Mike Love were among the many rock musicians who discovered the teachings of Maharishi Mahesh Yogi following the Beatles‘ public endorsement of his Transcendental Meditation technique in August 1967.[10] In December, the touring group attended a lecture by the Maharishi at a UNICEF Variety Gala in Paris[10] and were moved by the simplicity and effectiveness of his meditation process as a means to obtaining inner peace.[11] They were invited to meet the Maharishi in his hotel room the same day, and according to Brian, “they came back and [Carl was] just floating. … it got to me through him.”[12][nb 2] He recalled that he had “already been initiated” beforehand, but “for some ridiculous reason I hadn’t followed through with it, and when you don’t follow through with something you can get all clogged up. … we’re all meditating together now.”[12]

In a January 1968 interview, Brian stated that the group was unsure what their next production would be, but that “it won’t be very long now until I come up with a song about meditation. It shouldn’t be more than a month.”[12] He also expressed an interest in “pull[ing] out of conventional sound making and get[ting] into sounds that have never been made before ever.”[12] In early February, the group performed scattered gigs in the U.S. with Buffalo Springfield.[13] The Beach Boys attended the Maharishi’s public appearances in New York[14] and Cambridge, Massachusetts, after which he invited Love to join the Beatles at his training seminar in Rishikesh in northern India.[15] Love stayed there from February 28 to March 15.[14] In his absence, the rest of the group began recording the album that would become Friends.[16]

Recording history

[edit]

Friends was recorded primarily at the Beach Boys’ private studio, located within Brian’s Bel Air home, from late February to early April 1968.[17] It was written, performed, or produced mainly by the Wilson brothers with what Stebbins terms “a strong assist” from Al Jardine.[18] Jardine remembered how he still “felt that [Brian] had a lot to offer. … We wrote [most of the Friends music] at his house right under that beautiful stained glass Wild Honey cover window.”[19] He added: “We’d get together in the morning. A lot of activity took place in the kitchen. … We were in there as much as in the studio. God, we ate well.”[20]

It was the first Beach Boys album not to have Brian consistently as primary composer,[9] and the first to feature significant songwriting contributions from other group members.[21] Asked as to the level of Wilson’s input, band archivists Mark Linett and Alan Boyd said that Wilson led the entire project, even on the songs that he did not compose.[22] In a 1976 interview, Wilson referred to Friends as his second “solo album”, the first being Pet Sounds.[23] Stephen Desper was recruited as the band’s recording engineer, a role he would keep until 1972.[24] He had been recently contacted to convert Brian’s semi-portable home recording set-up to a more permanent “full-fledged recording studio with the capacity of any other”.[25] Session musicians were used more than on Smiley Smile and Wild Honey, but in smaller configurations than on the Beach Boys’ records from 1962 through 1966.[26]

From February 20 or 27 to March 15, the band tracked “Little Bird“, “Be Here in the Mornin'”, and “Friends”. After Love returned from his retreat, they began recording “When a Man Needs a Woman”, “Passing By”, “Busy Doin’ Nothin’“, “Wake the World“, “Meant for You”, “Anna Lee, the Healer”, and “Be Still”.[27][nb 3] By the spring of 1968, the Beach Boys were overdue to submit an album to Capitol, and so Brian rushed to finish the Friends album while his bandmates were on tour.[22] Sessions concluded with “Diamond Head” on April 12.[27] Desper mixed the album for stereo.[29] It was the band’s first album to be mixed and released exclusively in true stereo, as the band’s releases since The Beach Boys Today! (1965) had only been available in mono or Duophonic.[9]

Music and lyrics

[edit]

The LP has a relatively short length; only two of its 12 tracks last longer than three minutes, and five run short of two minutes.[24] In author Jon Stebbins‘ description, the album “reflects the peaceful and quietly centered aura” that the band had gained from their introduction to Transcendental Meditation.[18] Bruce Johnston described the album as a conscious attempt to make something “really subtle … that wasn’t concerned with radio”.[30] Retrospectively, the album may be viewed as the final installment in a consecutive three-part series of lo-fi Beach Boys albums.[2] Columnist Joel Goldenburg believes that the lightly produced album was the closest the group ever came to sunshine pop, a genre they had influenced but never fully embraced.[31]

For the album’s 1990 CD liner notes, Brian recalled that he “had a good thing rollin’ in my head. The bad things that had happened to me had taken their toll and I was free to find out just how much I had grown through the emotional pain that had come my way. … I think that the Beach Boys’ sound was evolving right along.”[21][nb 4] The few tracks where he served as primary author contained his usual composing trademarks, such as unexpected harmonic changes, descending stepwise progressions, and unusually structured musical phrases.[24] As on much of his compositions of the period, there was a heavy influence drawn from Burt Bacharach.[22]

Subject matter ranges from Transcendental Meditation to bearing children and “doin’ nothin'”.[32] Rolling Stone‘s Jim Miller characterized Friends as a “return to Smiley‘s dryness, minus the weirdness”. Musicologist Daniel Harrison said Miller’s observation was only true of “Meant for You”, and that the remaining songs “have few of the formal or harmonic quirks of the earlier album, though there is no lack of clever and interesting effects, such as the bass harmonica line in ‘Passing By’ or the repetitive monophonic organ line in the break of ‘Be Here in the Morning.'”[33] The group’s influences, according to rock critic Gene Sculatti, seemed to derive “primarily from Pet Sounds, Smiley Smile, Wild Honey, and little else. The characteristic innocence and somewhat childlike visions imparted to their music are applied directly to the theme of the album: friendships. As usual, the lyrics tend to be basic, yet as expressive as they need to be; words, like individual voices or instruments, are all part of the larger whole of music”.[34]

Johnston was unhappy with the group’s “wimpy” songs and opined that the new material—with the sole exception of the title track—did not represent Brian “at full strength”.[35] When asked why the band did not pursue harder rock styles, Jardine responded that “for Carl and me, we were painting a canvas. Jimi [Hendrix] was one of the best in the world, but they were more of a performance phenomenon, representing an era. … We didn’t have that need, because I think it’s a need.”[36] Brian similarly felt no pressure to make “heavy” music: “We never needed to. It’s already been done.”[37]

Content

[edit]

Side one

[edit]

“Meant for You” is a 38-second introduction to the album and the shortest song in the group’s catalog.[38] It was originally conceived as “You’ll Find it Too”,[39] with a longer runtime of about two minutes, and featured additional lyrics about a pony and a puppy.[40][nb 5]

The album’s title track was arranged in 3/4 time after Brian realized that waltzes were uncommon on the radio.[41]

Problems playing this file? See media help.

“Friends” is a waltz that was originally composed in 4/4 time.[41] The song was arranged and co-written by Brian,[21] who described it as his favorite on the album.[42] “Wake the World” was the first original songwriting collaboration between Brian and Jardine. It was another song that Brian said was “my favorite cut [on the album]. It was so descriptive to how I felt about the dramatic change over from day to night.”[21] The song is the first on the album that demonstrates his then-recent “a-day-in-a-life-of” songwriting habit.[43][nb 6]

“Be Here in the Mornin”” and “When a Man Needs a Woman” were written about some particular comforts of Brian’s daily life.[24] The former is another waltz[24] and features the Wilsons’ father Murry contributing a bass vocal.[45] The song makes a passing lyrical reference to the Wilsons’ cousin Steve Korthof, road manager Jon Parks, and Beach Boys manager Nick Grillo.[21] Parks and Korthof themselves shared a writing credit on “When a Man Needs a Woman”.[19] The song was inspired by Marilyn Wilson‘s pregnancy with her and Brian’s first child Carnie, although the lyric suggests that Brian thought it would be a boy.[13]

“Passing By” is wordless, with the melody hummed by Brian.[46] The piece had discarded lyrics written for it: “While walking down the avenue / I stopped to have a look at you / And then I saw / You were just passing by”.[21]

Side two

[edit]

“Anna Lee, the Healer” is about a masseuse Mike Love encountered in Rishikesh.[47] The arrangement consists only of vocals, piano, bass, and hand drumming.[48]

“Little Bird” was composed by Dennis Wilson with poet Stephen Kalinich, which Brian said “blew my mind because it was so full of spiritualness. He was a late bloomer as a music maker. He lived hard and rough but his music was as sensitive as anyone’s.”[21] The bridge section incorporates elements of “Child Is Father of the Man“, a then-unreleased song from Smile.[2] According to Kalinich, Brian composed virtually the entirety of “Little Bird”, but chose not to receive an official writing credit.[49]

“Be Still”, another Dennis/Kalinich song, only features Dennis’ singing[50] and Brian playing organ.[2] Biographer Peter Ames Carlin compared the song to a “Unitarian hymn” and interpreted the lyrics to be a description of “the sacred essence of life and the human potential to interact with God.”[51]

The lyrics of “Busy Doin’ Nothin’” reflect the minutiae of Wilson’s daily social and business life, while the music, he said, was inspired by “bossa nova in general”.[52]

Problems playing this file? See media help.

The final three tracks are genre experiments[48] that break stylistically from the rest of the album.[47] “Busy Doin’ Nothin’” is a flirtation with bossa nova, one of several autobiographic slice-of-life songs written by Brian during this era, and one of the only tracks on the album where he exclusively used session musicians.[21] The lyrics contain step-by-step instructions on how to find his house, albeit without mentioning where to start: “Drive for a couple miles / You’ll see a sign and turn left / For a couple blocks … “[53]

“Diamond Head” is an instrumental exotica lounge jam[47] that echoed the use of extended forms from Smile,[46] and is the album’s longest piece at 3 minutes and 39 seconds.[47] Biographer Mark Dillon surmised that it was likely inspired by the group’s visit to Hawaii during the previous year.[46]

“Transcendental Meditation” contrasts all that comes before it with its raucous tone.[47] Asked about the song, Dennis explained that the group “wanted to get away from anything that sounded too pompous, too religious. It would have been easy to do something peaceful, very Eastern, but we were trying to reach listeners on all levels.”[54] Jardine viewed it as a weak effort.[20]

Leftover

[edit]

Leftover tracks from the sessions include “Untitled #1”, “Away”, “Our New Home” (or “Our Happy Home”), “New Song” (unofficially known as “Spanish Guitar”), “You’re As Cool As Can Be”, covers of Burt Bacharach and Hal David‘s “My Little Red Book” and Buffalo Springfield’s “Rock & Roll Woman“, a demo for “Time to Get Alone“, and an early version of “All I Wanna Do“.[27] “Our Happy Home” was described by music journalist Brian Chidester as “a short, bouncy riff that maintains the gentle air of the Friends sessions”.[2] It was later reworked as “Our Sweet Love” for their 1970 album Sunflower, along with “All I Wanna Do”.[55] “New Song” contains a melody that was recycled for “Transcendental Meditation”. “You’re As Cool As Can Be” is an instrumental of unknown authorship that features an upbeat piano melody played by Brian.[2] “Away” was a song Dennis wrote with touring musician Billy Hinsche in December 1967.[56]

Maharishi tour

[edit]

Main article: The Beach Boys’ 1968 US tour with Maharishi Mahesh Yogi

On April 5, 1968,[27] the band began “the Million Dollar Tour”, a series of self-financed concerts across the American south.[57] Featuring Buffalo Springfield and Strawberry Alarm Clock as supporting acts,[27][58] these shows were poorly attended due in part to the political mood following the assassination of Martin Luther King that April.[16] Six of the 35 dates were canceled, while two were rescheduled.[27] They lost $350,000 in expected revenue (equivalent to $3.07 million in 2023).[59] Mike Love arranged that the group tour the U.S. with the Maharishi in May. According to Nick Grillo, the band hoped that touring with the Maharishi would recuperate some of their financial losses.[60] The Beatles also became disenchanted with the Maharishi and the Spiritual Regeneration Movement and publicly expressed their concerns around this time, which had a detrimental effect on the guru’s standing among music fans. In Stebbins’ description, the Maharishi became a pariah.[61]

The shows with the Maharishi were advertised as “The Most Exciting Event of the Decade!” and comprised a set of songs by the Beach Boys followed by the Maharishi’s lecture on the benefits of meditation.[62] The tour started on May 3 and ended abruptly after five shows. A performance at the Singer Bowl in Queens, New York was canceled twenty minutes before the group were scheduled to perform when only 800 people showed up to the 16,000-capacity venue.[63] Writing in New York magazine, Loraine Alterman reported on the hostile audience reaction to the Maharishi but said that the songs the band included from Friends worked well beside the group’s previous hits “because they were happy and full of love”. She added that, unlike the Maharishi’s lecture, the song “Transcendental Meditation” “did not tax anyone’s brain. It just repeated how transcendental meditation ‘makes you feel grand’ against a moving beat.”[64]

Because of the disappointing audience numbers and the Maharishi’s subsequent withdrawal to fulfill film contracts, the remaining 24 tour dates were canceled at a cost estimated at $250,000 for the band (equivalent to $2.19 million in 2023).[7] Afterward, Love and Carl told journalists that the racial violence following King’s assassination was to blame for the tour’s demise. Carl said: “A lot of people just would not let their children out. Nobody wants to get hurt.” He added that the group’s goal was to appeal mainly to young people, “but not the teeny-boppers“, while Love commented that the shows were “not put together for commercial purposes”.[65] In his 2016 autobiography, Love wrote: “I take responsibility for an idea that didn’t work. But I don’t regret it. I thought I could do some good for people who were lost, confused, or troubled, particularly those who were young and idealistic but also vulnerable, and I thought that was true for a whole bunch of us.”[66][nb 7]

Sleeve design

[edit]

Friends was packaged with a cover artwork, designed by David McMacken, that depicted the band members in a psychedelic visual style.[68] Love remembered that the group lacked “savvy marketing and design”, and that while in Rishikesh, Paul McCartney had urged him “to take more care of what you put on your album covers”.[69] Johnston opined that the Friends cover ultimately ranked second to Pet Sounds for being the worst “in the history of the music business”.[35] Matijas-Mecca said the artwork “did nothing to convince anyone that the Beach Boys were in touch with anything in particular”.[17]

Release

[edit]

Friends came out just after Hendrix and Cream. The whole country had discovered drugs, discovered words, discovered Marshall amplifiers, and here comes this feather floating through a wall of noise.

—Bruce Johnston, 2007[30]

Lead single “Friends” was issued on April 8 and reached number 47 on the Billboard Hot 100,[18] making it their lowest-charting single in six years.[30] On June 4, the Beach Boys appeared on The Les Crane Show and discussed their support of the Maharishi.[70][nb 8] The Friends album followed on June 24.[50]

On July 2, the group embarked on a three-week U.S. tour with further dates continuing throughout August, including some stops in Canada.[71] Their setlists included “Friends”, “Little Bird”, and “Wake the World”. Several supporting musicians accompanied the group (keyboardist Daryl Dragon, bassist Ed Carter, percussionist Mike Kowalski, and a brass section).[72] Johnston remembered that performing the Friends songs caused him to “wince”, and that it was difficult to maintain the “subtle” nature of the songs in a live setting.[35]

On July 6, Friends debuted on the Billboard Top LPs chart at number 179[73] and subsequently peaked at number 126 while artists such as the Doors and Cream occupied the top positions.[50] On July 8, the band released “Do It Again” as a standalone single backed with “Wake the World”. “Do It Again” was recorded within the prior two months as a self-conscious throwback to the group’s early surf songs, and the first time they had embraced the subject matter since 1964.[74][nb 9] It reached the top twenty in the U.S. and was a number one hit in the UK. When Friends was issued in Japan, the song was included in the album’s track list.[19]

Love recalled that the album’s commercial failure caused Capitol to “panic”.[75] On August 5, the label issued the greatest hits album Best of the Beach Boys Vol. 3 to recuperate from the LP’s poor sales. Matijas-Mecca wrote that this was a sign that the label had “given up” on the group, repeating a tactic they used after the release of Pet Sounds and again with Smiley Smile.[76] While the first two volumes were quickly certified as gold records, biographer David Leaf said that the label was “more than a little horrified to watch [the third volume] sink like a stone, unable to even outperform Friends.”[21] A collection of Beach Boys backing tracks, Stack-o-Tracks, was issued by Capitol on August 19. The album became the first Beach Boys LP that failed to chart in the U.S. and UK.[77] Friends ended its 10-week stay on the Billboard charts on September 7.[21] Ultimately, the album’s record sales in the U.S. (estimated at 18,000 units)[78] were the group’s worst to date.[21] In the UK, the album fared better, reaching number 13 on the UK Albums Chart.[21]

Critical reception

[edit]

Contemporary

[edit]

Friends received a number of positive reviews, but according to historian Keith Badman, most were published “too late to influence sales”.[79] According to a Mojo retrospective, the band’s remaining fanbase reacted to the album with the abandonment of “any hope that Brian Wilson would deliver a true successor to his 1966 masterwork”, Pet Sounds.[30] Stebbins noted that its “quirky gentleness in the context of political protests, race riots, and the war-torn social landscape of 1968 [made] it about as square a peg as one can imagine”.[50] Music critic Richie Unterberger said that the group lost most of their audience by being “less experimental” with their music.[80]

Upon release, a Billboard reviewer predicted that “the group should score high on the charts” with the album and highlighted “Anna Lee, the Healer” and “Transcendental Meditation” as “catchy numbers”.[1] Rolling Stone‘s Arthur Schmidt wrote in his review of the album: “Everything on the first side is great. … Listen once and you might think this album is nowhere. But it’s really just at a very special place, and after a half-dozen listenings, you can be there.”[81] Jazz & Pop‘s Gene Sculatti reported that there were detractors of the Beach Boys who most frequently took issue with the band’s “apparently excessive immersion in and identification with mass culture and ‘commercialism'”. In spite of such criticisms, he deemed Friends “[perhaps] their best” work yet, calling it “the culmination of the efforts and the results of their last three LPs. … It is another showcase for what is the most original and perhaps the most consistently satisfying rock music being created today.”[34]

In his review for NME, Allen Evans commented on the brevity of several of the tracks and described “Transcendental Meditation” as “a weirdo piece” and “Passing By” as “quite delightful” in its use of “voices … as instruments”. He concluded: “Varied and interesting, though maybe not their best LP.”[82] Writing in the same publication’s annual for 1968, Keith Altham reported that “Do It Again” “seemed like two steps backwards” but had nevertheless re-established the Beach Boys as hit-makers, while Friends received “considerable criticism from critics who complained that one entire side of the album lasted just a few minutes longer than the hit single ‘MacArthur Park‘”.[83] In Disc & Music Echo, Penny Valentine wrote of the “Friends” single, “Whither the progressive Beach Boys? … If The Beach Boys are as bored as they sound, they should stop bothering … They are no longer the brilliant Beach Boys. They are grey and they are making sad little grey records.”[84] Record Mirror‘s David Griffiths referred to “Transcendental Meditation” as “the most disappointing Beach Boys track of the year”.[54]

Retrospective

[edit]

| Review scores | |

|---|---|

| Source | Rating |

| AllMusic | |

| Blender | |

| Encyclopedia of Popular Music | |

| MusicHound | 3/5[87] |

| Q | |

| The Rolling Stone Album Guide | |

In its 1990 liner notes, David Leaf wrote that Friends was since reevaluated as “one of the Beach Boys’ finest artistic efforts,”[21] whereas critic Will Hermes wrote in 2019: “The music from this period has generally been considered subpar by the impossible-to-match standards set by Pet Sounds“.[22] AllMusic‘s Donald A. Guarisco described the album as a “cult favorite” among hardcore fans and highlighted the title track as “mellow”, “lovely”, and “a good example of the Beach Boys’ late-’60s output: it is far less musically complex than ‘California Girls‘ or ‘Wouldn’t It Be Nice‘ but possesses a homespun charm all its own.”[3]

An uncredited writer for Mojo opined that “Given distance and hindsight … Friends is a uniquely rewarding Beach Boys album that, excepting Pet Sounds, is the group’s most sonically and thematically unified.”[30] The A.V. Club contributor Noel Murray said the album was “lovely” and one of the group’s “warmest and most spiritual records”.[32] Brooklyn Vegan‘s Andrew Sacher characterized it as “the most underrated Beach Boys album”, “prettier and less quirky” than Smiley Smile and Wild Honey, and lamented that it is not as widely praised as the Byrds‘ contemporary effort The Notorious Byrd Brothers.[48]

Jason Fine wrote in the 2004 edition of The Rolling Stone Album Guide: “If you can get past sappy wannabe-hippie tracks such as ‘Wake the World’ and ‘Transcendental Meditation’, the album is gorgeous, with standout moments including ‘Meant for You’, one of Mike Love’s finest vocals, and Brian’s ‘Busy Doin’ Nothin””.[89] In his review for AllMusic, Richie Unterberger said that, relative to its unveiling in 1968, “Today [the album] sounds better, but it’s certainly one of the group’s more minor efforts”, adding that the production and harmonies “remained pleasantly idiosyncratic, but there was little substance at the heart of most of the songs.”[80] In 1971, Robert Christgau dismissed Friends as the band’s “worstever” work.[90] Biographer Steven Gaines described the LP as “boring” and “emotionless”.[91]

Among other musicians, journalist and Saint Etienne co-founder Bob Stanley called the album a “lost gem” with a “timeless quality in its simplicity, underlined by the basic instrumentation”.[78] Paul Weller named it as one of his favorite albums of all time.[92] It was voted number 662 in the third edition of Colin Larkin‘s All Time Top 1000 Albums (2000).[93]

Legacy

[edit]

In his book Turn Off Your Mind: The Mystic Sixties and the Dark Side of the Age of Aquarius, Gary Lachman describes Friends as “the Beach Boys TM album” and considers their public association with the Maharishi to have been a “disastrous flirtation” that, for Dennis Wilson, was soon superseded by a more damaging personal association with the Manson Family cult.[94] Despite the ignominy of the tour, the Beach Boys remained ardent supporters of the Maharishi and Transcendental Meditation.[95] They continued to record songs inspired by the Maharishi or his teachings, including both “He Come Down” and “All This Is That” on 1972’s Carl and the Passions,[96] and both “Everyone’s in Love with You” and “T M Song” on 1976’s 15 Big Ones.[97][nb 10] Subsequent albums would also see Dennis contribute more songs, eventually culminating in a solo record, 1977’s Pacific Ocean Blue.[21]

Stebbins recognizes Friends as marking “the true beginning of the Beach Boys as a group of six relatively equal creative partners”.[18] It was the last Beach Boys album where Brian held most of the writing or co-writing credits until 1977’s The Beach Boys Love You.[99] The band’s following album 20/20 was released in February 1969, with a substantial portion of the LP consisting of leftover singles recorded in 1968 and outtakes from earlier albums. Brian produced virtually none of the post-Friends recordings.[100]

In the summer of 1969, Brian worked with Stephen Kalinich to produce a spoken-word LP, A World of Peace Must Come, which included an extended run-through of “Be Still”. The album was not released until 2008.[2] Shortly after the sale of Sea of Tunes, friend Stanley Shapiro persuaded Brian to rewrite and rerecord a number of Beach Boys songs to restore his public and industry reputation. After contacting fellow songwriter Tandyn Almer for support, the trio spent a month reworking cuts from Friends,[101] including “Passing By”, “Wake the World”, “Be Still”, and the album’s title track.[2] As Shapiro handed demo tapes to A&M Records executives, they found the product favorable before they learned of Wilson and Almer’s involvement, and refused to support the project. Most of these recordings remain unreleased.[101]

In November 1974, a double album reissue that paired Friends and Smiley Smile hit number 125 on the Billboard 200.[102] Brian cited Friends as his favorite Beach Boys album,[103][30] and said that while Smile “had potential … Friends has been good listening no matter what mood I’m in.”[24] He rerecorded “Meant for You” for his 1995 solo album I Just Wasn’t Made for These Times[46] and performed songs from the Friends album live with Jardine in 2019.[104] Among cover versions of the Friends tracks: Pizzicato Five recorded “Passing By” for their album Sister Freedom Tapes (1996),[105] and the High Llamas contributed a version of “Anna Lee, the Healer” to the tribute album Caroline Now!: The Songs of Brian Wilson and the Beach Boys (2000).[106] Noel Murray remarked that without Friends, “the High Llamas probably wouldn’t exist.”[32][nb 11] Lo-fi musician R. Stevie Moore based his 1975 song “Wayne Wayne (Go Away)” on Friends.[109]

Track listing

[edit]

Original release

[edit]

| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Lead vocal(s) | Length |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | “Meant for You” | Brian WilsonMike Love | Love | 0:38 |

| 2. | “Friends“ | B. WilsonCarl WilsonDennis WilsonAl Jardine | C. Wilson with B. Wilson | 2:32 |

| 3. | “Wake the World“ | B. WilsonJardine | B. Wilson with C. Wilson | 1:29 |

| 4. | “Be Here in the Mornin'” | B. WilsonC. WilsonD. WilsonLoveJardine | Jardine and C. Wilson[110] | 2:17 |

| 5. | “When a Man Needs a Woman” | B. WilsonD. WilsonC. WilsonJardineSteve KorthofJon Parks | B. Wilson | 2:07 |

| 6. | “Passing By” | B. Wilson | B. Wilson, C. Wilson, and Al Jardine | 2:24 |

| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Lead vocal(s) | Length |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | “Anna Lee, the Healer” | B. WilsonLove | Love | 1:51 |

| 2. | “Little Bird“ | D. WilsonSteve Kalinich | D. Wilson and B. Wilson | 2:02 |

| 3. | “Be Still” | D. WilsonKalinich | D. Wilson | 1:24 |

| 4. | “Busy Doin’ Nothin’“ | B. Wilson | B. Wilson | 3:05 |

| 5. | “Diamond Head” | Al VescovoLyle RitzJim AckleyB. Wilson | instrumental | 3:39 |

| 6. | “Transcendental Meditation” | B. WilsonLoveJardine | B. Wilson | 1:51 |

| Total length: | 25:32 | |||

Track information per David Leaf.[21]

Friends / 20/20 1990/2001 CD reissue bonus tracks

[edit]

| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Lead vocal(s) | Length |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 13. | “Break Away“ | B. Wilson, Murry Wilson | C. Wilson, Jardine with B. Wilson | 2:57 |

| 14. | “Celebrate the News” | D. Wilson, Gregg Jakobson | D. Wilson | 3:05 |

| 15. | “We’re Together Again” | Ron Wilson | B. Wilson | 1:49 |

| 16. | “Walk On By“ | Burt Bacharach, Hal David | B. Wilson with D. Wilson | 0:55 |

| 17. | “Old Folks at Home/Ol’ Man River“ | Stephen Foster, Jerome Kern, Oscar Hammerstein II | B. Wilson with Love | 2:52 |

Wake the World

[edit]

| Wake the World: The Friends Sessions | |

|---|---|

| Compilation album by the Beach Boys | |

| Released | December 7, 2018 |

| Recorded | 1966–1971 |

| Length | 67:43 |

| Label | Capitol |

| Producer | The Beach Boys (original recordings)Mark LinettAlan Boyd |

| Compiler | Mark LinettAlan Boyd |

| The Beach Boys chronology | |

| The Beach Boys with the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra (2018)Wake the World: The Friends Sessions (2018)I Can Hear Music: The 20/20 Sessions (2018) | |

| Review scores | |

|---|---|

| Source | Rating |

| AllMusic | |

| Rolling Stone | |

On December 7, 2018, Capitol released Wake the World: The Friends Sessions, a digital-only compilation. Included are session highlights, outtakes, and alternate versions of Friends tracks, as well as some unreleased material by Dennis and Brian Wilson.[113] It is the successor to 1967 – Sunshine Tomorrow from the previous year.[22] Along with I Can Hear Music: The 20/20 Sessions, Wake the World was not issued on physical media due to the record company’s wish not to interfere with the release of The Beach Boys with the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra.[114]

| No. | Title | Writer(s) | Length |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | “Meant for You” (alternate version with session intro) | Brian WilsonMike Love | 2:17 |

| 2. | “Friends” (backing track) | B.WilsonCarl WilsonDennis WilsonAl Jardine | 2:38 |

| 3. | “Friends” (a cappella) | B. WilsonC. WilsonD. WilsonJardine | 2:20 |

| 4. | “Wake the World” (alternate version) | B. WilsonJardine | 2:12 |

| 5. | “Be Here in the Morning” (backing track) | B. WilsonC. WilsonD. WilsonMike LoveJardine | 2:20 |

| 6. | “When a Man Needs a Woman” (early take) | B. WilsonD. WilsonJardineSteve KorthofJon Parks | 0:50 |

| 7. | “When a Man Needs a Woman” (alternate version) | B. WilsonD. WilsonJardineKorthofParks | 2:08 |

| 8. | “Passing By” (alternate version) | B. Wilson | 1:44 |

| 9. | “Anna Lee the Healer” (session excerpt) | B. WilsonLove | 1:22 |

| 10. | “Anna Lee the Healer” (a cappella) | B. WilsonLove | 1:54 |

| 11. | “Little Bird” (backing track) | D. WilsonStephen Kalinich | 2:00 |

| 12. | “Little Bird” (a cappella) | D. WilsonKalinich | 2:04 |

| 13. | “Be Still” (alternate take with session excerpt) | D. WilsonKalinich | 2:09 |

| 14. | “Even Steven” (early version of “Busy Doin’ Nothin’”) | B. Wilson | 2:52 |

| 15. | “Diamond Head” (alternate version with session excerpt) | Al VescovoLyle RitzJim AckleyB.Wilson | 4:33 |

| 16. | “New Song (Transcendental Meditation)” (backing track with partial vocals) | B. Wilson | 1:51 |

| 17. | “Transcendental Meditation” (backing track with session excerpt) | B. WilsonLoveJardine | 2:22 |

| 18. | “Transcendental Meditation” (a cappella) | B. WilsonLoveJardine | 1:52 |

| 19. | “My Little Red Book“ | Burt BacharachHal David | 2:48 |

| 20. | “Away” | D. WilsonBilly Hinsche | 0:57 |

| 21. | “I’m Confessin'” (demo) | B. Wilson | 2:17 |

| 22. | “I’m Confessin'”/”You’re as Cool as Can Be” (take 1) | B. Wilson | 1:38 |

| 23. | “You’re as Cool as Can Be” (take 2) | B. Wilson | 1:14 |

| 24. | “Be Here In The Morning Darling” | B. Wilson | 3:29 |

| 25. | “Our New Home” | B. Wilson | 2:02 |

| 26. | “New Song” | B. Wilson | 1:26 |

| 27. | “Be Still” (alternate track) | D. WilsonKalinich | 1:03 |

| 28. | “Rock and Roll Woman“ | Stephen Stills | 2:19 |

| 29. | “Time to Get Alone” (alternate version demo) | B. Wilson | 2:04 |

| 30. | “Untitled 1/25/68” | D. Wilson | 1:07 |

| 31. | “Passing By” (demo) | B. WilsonStanley ShapiroTandyn Almer | 2:34 |

| 32. | “Child Is Father of the Man” (original 1966 track mix) | B. Wilson | 3:36 |

| Total length: | 67:43 | ||

Personnel

[edit]

Per band archivist Craig Slowinski.[115]

The Beach Boys

- Al Jardine – vocals, electric bass (on “Passing By” [uncertain credit])

- Bruce Johnston – vocals, keyboard (on “Passing By”), piano (on “Meant for You”)

- Mike Love – vocals

- Brian Wilson – vocals, organ (on “Meant for You”, “When a Man Needs a Woman”, “Passing By”, “Be Here in the Mornin'”, and “Be Still”), piano (on “Wake the World” and “Anna Lee the Healer”), percussion (on “Diamond Head” [uncertain credit])

- Carl Wilson – vocals, guitar (on “Friends”, “When a Man Needs a Woman”, and “Passing By”), bass (on “Anna Lee the Healer”)

- Dennis Wilson – vocals, harmonium (on “Little Bird”), congas (on “Anna Lee the Healer” [uncertain credit])

Guests

- Marilyn Wilson – vocals (on “Busy Doin’ Nothin'” and “Be Here in the Mornin’), wordless vocals (on “Passing By” [uncertain credit])

- Murry Wilson – vocals (on “Be Here in the Mornin'”)

Session musicians

- Jim Ackley – keyboard, guitar

- Arnold Belnick – violin

- Jimmy Bond – upright bass

- Norman Botnick – viola

- David Burk – viola

- David Cohen – guitar

- Roy Caton – trumpet

- John DeVoogt – violin

- Bonnie Douglas – violin

- Don Englert – clarinet, saxophone

- Alan Estes – vibraphone, woodblocks, chimes

- Dick Forrest – trumpet

- Jim Gordon – drums, woodblocks, bell, congas, timbales

- Bill Green – saxophone

- Jim Horn – saxophone, clarinet

- Dick Hyde – tuba, flugelhorn

- Norm Jeffries – drums

- Robert T. Jung – saxophone

- Meyer Hirsch J. Kenneth Jensen – saxophone

- Raymond Kelley – cello

- William Kurasch – violin

- Jacqueline Lustgarden – cello

- Tommy Morgan – harmonica, bass harmonica

- Leonard Malarsky – violin

- Jay Migliori – saxophone, clarinet, bass clarinet

- Ollie Mitchell – trumpet

- Gene Pello – drums

- Bill Perkins – saxophone

- Lyle Ritz – electric bass, upright bass, ukulele

- Jay Rosen – violin

- Ralph Schaeffer – violin

- Tom Scott – bass flute, saxophone

- David Sherr – oboe, saxophone

- Paul Shure – violin

- Tony Terran – trumpet

- Al Vescovo – banjo, guitar, lap steel guitar

Technical staff

- Jim Lockert – engineer

Charts

[edit]

| Chart (1968) | Peak position |

|---|---|

| US Billboard 200[116] | 126 |

Notes

[edit]

- ^ From 1968 onward, Brian’s songwriting output declined substantially, but the public narrative of “Brian-as-leader” continued. In the belief of Wilson biographer Christian Matijas Mecca, “it is here that the ‘Brian-is-the-Beach-Boys’ era comes to a close. … After Wild Honey, the Beach Boys were no longer Brian’s creative vehicle, in spite of what the band might have preferred that their fans, the press, or their successive record companies, to believe.”[9]

- ^ He felt that religion and meditation were the same and that “for the first time in, God, I don’t know how many millions of years, or thousands or hundreds, everybody has got a personal path to God”.[12]

- ^ Love only appears on four songs (“Meant for You”, “Wake the World”, “Anna Lee, the Healer”, and “Be Here in the Morning”).[28]

- ^ Jardine supported, “He [Brian] was feeling a little bit better about himself. I remember him being pretty stable and happy then because we were obviously working together and he was still being very creative.”[20]

- ^ This version was released in 2013 for the compilation Made in California

- ^ Preceded by “I’d Love Just Once to See You” and “Time to Get Alone” from the Wild Honey sessions.[44]

- ^ Jon Stebbins lists the Maharishi tour—specifically, that the band “toured with the Maharishi after the Beatles had rejected him”—among the Beach Boys’ major “artistic missteps” that also included their cancellation of the Smile album and their refusal to perform at the 1967 Monterey Pop Festival.[67]

- ^ The program was aired on the ABC network on June 13.[70]

- ^ Love thought that while the group’s democratic approach “allow[ed] the rest of us to grow musically, [we] would never replicate our past success”, and to that end, he engaged Brian in co-writing “Do It Again”.[75]

- ^ 1978’s M.I.U. Album was named so because it was recorded at the Maharishi International University in Iowa.[98]

- ^ When they released their 1994 album Gideon Gaye, it was dubbed “the best Beach Boys album since 1968’s Friends“.[107][108]

References

[edit]

- ^ Jump up to:a b “Album Reviews”. Billboard. Vol. 80, no. 25. June 22, 1968. p. 85. ISSN 0006-2510.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f g h Chidester, Brian (March 7, 2014). “Busy Doin’ Somethin’: Uncovering Brian Wilson’s Lost Bedroom Tapes”. Paste. Archived from the original on December 11, 2014. Retrieved December 11, 2014.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Guarisco, Donald A. “Friends”. AllMusic. Retrieved May 26, 2018.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Leaf, David (1990). Smiley Smile/Wild Honey (CD Liner). The Beach Boys. Capitol Records.

- ^ Hart, Ron (July 20, 2017). “5 Treasures on the Beach Boys’ New ‘1967—Sunshine Tomorrow'”. New York Observer. Retrieved May 27, 2018.

- ^ Doe, Andrew G. “Sessions 1967”. Bellagio 10452. Endless Summer Quarterly. Retrieved May 27, 2018.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Gaines 1986, pp. 195–197.

- ^ Matijas-Mecca 2017, pp. 83, 85.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Matijas-Mecca 2017, p. 83.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Love 2016, p. 176.

- ^ Badman 2004, p. 208.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e Highwater 1968.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Badman 2004, p. 214.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Badman 2004, p. 212.

- ^ Shumsky 2018, p. 225.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Carlin 2006, p. 135.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Matijas-Mecca 2017, p. 85.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d Stebbins 2011, p. 115.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Beard, David (July 2, 2008). “Cover Story: ‘Friends’ The Beach Boys’ Feel-Good Record”. Goldmine Magazine: Record Collector & Music Memorabilia. Retrieved May 27, 2018.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Sharp, Ken (July 28, 2000). “Alan Jardine: A Beach Boy Still Riding The Waves”. Goldmine.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Leaf, David (1990). Friends / 20/20 (CD Liner). The Beach Boys. Capitol Records.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e Hermes, Will (January 15, 2019). “How the Beach Boys’ Lost Late-Sixties Gems Got a Second Life”. Rolling Stone. Retrieved January 16, 2019.

- ^ Rensin, David (December 1976). “A Conversation With Brian Wilson”. Oui.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f Matijas-Mecca 2017, p. 86.

- ^ Gaines 1986, pp. 207–208.

- ^ Dillon 2014, p. 164.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f Doe, Andrew G. “Sessions 1968”. Bellagio 10452. Endless Summer Quarterly. Retrieved October 18, 2021.

- ^ “Friends”. smileysmile.net.

- ^ White 1996, p. 283.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f Mojo 2007, p. 132.

- ^ Goldenburg, Joel (February 27, 2016). “Joel Goldenberg: Sunshine pop offered some respite from ’60s strife”. The Suburban. Retrieved May 27, 2018.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Murray, Noel (October 16, 2014). “A beginner’s guide to the sweet, stinging nostalgia of The Beach Boys”. The A.V. Club.

- ^ Harrison 1997, p. 51.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Sculatti, Gene (September 1968). “Villains and Heroes: In Defense of the Beach Boys”. Jazz & Pop. Archived from the original on July 14, 2014.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Sharp, Ken (September 4, 2013). “Bruce Johnston On the Beach Boys’ Enduring Legacy (Interview)”. Rock Cellar Magazine. Archived from the original on September 19, 2018. Retrieved September 2, 2018.

- ^ Fanelli, Damian (May 14, 2015). “Al Jardine Dives Deep Into Beach Boys History, Working with the Wrecking Crew and Touring with Jeff Beck”. Guitar World. Retrieved October 23, 2018.

- ^ Coyne, Wayne (2000). “Playing Both Sides of the Coyne Part One”. Stop Smiling. No. 9.

- ^ Dillon 2014, p. 166.

- ^ Badman 2004, p. 215.

- ^ Atkins, Jamie (2013). “THE BEACH BOYS MADE IN CALIFORNIA”. Record Collector Mag. Retrieved June 25, 2018.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Benci, Jacopo (January 1995). “Brian Wilson interview”. Record Collector (185). UK.

- ^ Wilson, Brian (January 29, 2014). “Brian Answer’s Fans’ Questions In Live Q&A”. brianwilson.com. Archived from the original on February 24, 2021. Retrieved June 27, 2014.

- ^ Matijas-Mecca 2017, pp. xxii, 84, 86.

- ^ Matijas-Mecca 2017, p. xxii.

- ^ Wilson & Greenman 2016, p. 153.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d Dillon 2014, p. 167.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e Matijas-Mecca 2017, p. 87.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Sacher, Andrew (February 9, 2016). “Beach Boys Albums Ranked Worst to Best”. Brooklyn Vegan.

- ^ Dillon 2014, pp. 159–162.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d Stebbins 2011, p. 116.

- ^ Carlin 2006, p. 215.

- ^ “Brian Answer’s Fans’ Questions in Live Q&A”. January 29, 2014. Archived from the original on February 24, 2021. Retrieved June 27, 2014.

- ^ Planer, Lindsey. “Busy Doin’ Nothin'”. AllMusic. Retrieved May 26, 2018.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Griffiths, David (December 21, 1968). “Dennis Wilson: “I Live With 17 Girls””. Record Mirror.

- ^ Boyd, Alan (December 20, 2018). “Re: 1968 Copyright Extension Release Thread”. smileysmile.net. Retrieved December 23, 2018.

- ^ Badman 2004, p. 207.

- ^ Love 2016, pp. 197–198.

- ^ Mrfarmer (June 15, 2011). “On the road: Beach Boys, Buffalo Springfield”. strawberryalarmclock.com. Strawberry Alarm Clock. Retrieved June 22, 2018.

- ^ Badman 2004, p. 218.

- ^ Gaines 1986, p. 197.

- ^ Stebbins 2011, p. 254.

- ^ Carlin 2006, pp. 135–136.

- ^ Badman 2004, p. 219.

- ^ Alterman, Loraine (May 6, 1968). “The Maharishi, The Beach Boys and the Heathens”. New York.

- ^ “Beach Boys’ summer swing to hit 40-plus major spots”. Amusement Business. June 29, 1968.

- ^ Love 2016, p. 199.

- ^ Stebbins 2011, p. 150.

- ^ Morgan 2015, p. 152.

- ^ Love 2016, p. 186.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Badman 2004, p. 221.

- ^ Badman 2004, pp. 223–225.

- ^ Erlewine, Stephen Thomas (2019). “The Beach Boys On Tour: 1968”. AllMusic.

- ^ “Billboard 200 The Week of July 6, 1968”. Billboard. n.d. Retrieved November 22, 2018.

- ^ Badman 2004, pp. 221–223.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Love 2016, p. 200.

- ^ Matijas-Mecca 2017, pp. 51, 88.

- ^ Schinder 2007, pp. 120–121.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Stanley, Bob (n.d.). “The Beach Boys and Friends: Their Forgotten Gem”. BBC.co.uk. Retrieved June 15, 2018.

- ^ Badman 2004, p. 222.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Unterberger, Richie. “Friends”. AllMusic. Retrieved May 27, 2018.

- ^ Schmidt, Arthur (August 24, 1968). “Friends”. Rolling Stone. Retrieved January 13, 2018.

- ^ Evans, Allen (September 14, 1968). “LPs Page”. NME. p. 10.

- ^ Altham, Keith (December 1968). “Beach Boys Pulled Out Of Doldrums”. New Musical Express Annual.

- ^ Badman 2004, p. 220.

- ^ Wolk, Douglas (2004). “Friends/20/20”. Blender. Archived from the original on June 30, 2006.

- ^ Larkin 2006, p. 479.

- ^ Graff & Durchholz 1999, p. 83.

- ^ “The Beach Boys Friends; 20/20“. Q. June 2001. pp. 126–27.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Fine 2004, pp. 46, 48.

- ^ Christgau, Robert (October 14, 1971). “Consumer Guide (19)”. The Village Voice. New York. Retrieved April 14, 2013.

- ^ Gaines 1986, p. 198.

- ^ EW Staff (September 30, 2005). “Paul Weller lists 12 must-have CDs”. Entertainment Weekly.

- ^ Colin Larkin, ed. (2000). All Time Top 1000 Albums (3rd ed.). Virgin Books. p. 216. ISBN 0-7535-0493-6.

- ^ Lachman 2001, pp. 288, 318.

- ^ Shumsky 2018, pp. 161–162.

- ^ McCaughey, Scott (2000). Carl and the Passions – “So Tough” / Holland (CD Liner). The Beach Boys. Capitol Records.

- ^ Diken, Dennis; Buck, Peter (2000). 15 Big Ones/Love You (booklet). The Beach Boys. Capitol Records. p. 2.

- ^ Tamarkin, Jeff (2000). M.I.U./L.A. Light Album (booklet). The Beach Boys. California: Capitol Records.

- ^ Schinder 2007, pp. 120, 124.

- ^ Gaines 1986, p. 213.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Carlin 2006, pp. 172–173.

- ^ “Friends & Smiley Smile”. Billboard. Retrieved November 26, 2018.

- ^ Dillon 2014, pp. 159–168.

- ^ Lewis, Randy (13 September 2019). “Brian Wilson shakes off concerns with confident, star-studded show at the Greek”. Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 27 March 2021.

- ^ Mills, Ted. “Sister Freedom Tapes”. AllMusic. Retrieved May 25, 2018.

- ^ Ankeny, Jason. “Caroline Now!: The Songs of Brian Wilson and the Beach Boys”. AllMusic. Retrieved August 2, 2014.

- ^ Harrington, Richard (February 20, 2004). “High Llamas Keeping It Simple”. The Washington Post.

- ^ Lester, Paul (June 1998). “The High Llamas: Hump Up the Volume”. Uncut. (subscription required)

- ^ Mason, Stewart. “Stevie Moore Often/Pica Elite”. AllMusic. Retrieved May 25, 2018.

- ^ Slowinski, Craig (July 6, 2018). “Re: Be Here In The Mornin’ Question”. Smiley Smile. Retrieved July 26, 2018.

- ^ Erlewine, Stephen Thomas (2019). “Wake the World: The Friends Sessions”. AllMusic.

- ^ Hermes, Will (January 18, 2019). “Review: Beach Boys Plumb Vaults for Post-‘Pet Sounds’ Gems”. Rolling Stone.

- ^ “Happy New Music Friday! ‘Wake the World: The Friends Sessions’ Is Out Now!”. thebeachboys.com. December 7, 2018. Archived from the original on December 10, 2018. Retrieved December 9, 2018.

- ^ Willman, Chris (August 31, 2021). “Beach Boys’ Archivists on the ‘Feel Flows’ Boxed Set, and How the Group Was Peaking — Again — While the World Wasn’t Looking”. Variety. Retrieved August 31, 2021.

- ^ Endless Summer Quarterly, Spring 2018 Edition[full citation needed]

- ^ “The Beach Boys Chart History (Billboard 200)”. Billboard. Retrieved September 26, 2017.

Bibliography

[edit]

- Badman, Keith (2004). The Beach Boys: The Definitive Diary of America’s Greatest Band, on Stage and in the Studio. Backbeat Books. ISBN 978-0-87930-818-6.

- Carlin, Peter Ames (2006). Catch a Wave: The Rise, Fall, and Redemption of the Beach Boys’ Brian Wilson. Rodale. ISBN 978-1-59486-320-2.

- Dillon, Mark (2014). Fifty Sides of the Beach Boys: The Songs That Tell Their Story. ECW Press. ISBN 978-1-77090-198-8.

- Fine, Jason (2004). “The Beach Boys”. In Brackett, Nathan; Hoard, Christian (eds.). The New Rolling Stone Album Guide (4th ed.). New York City: Fireside/Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-7432-0169-8.

- Harrison, Daniel (1997). “After Sundown: The Beach Boys’ Experimental Music” (PDF). In Covach, John; Boone, Graeme M. (eds.). Understanding Rock: Essays in Musical Analysis. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-988012-6.

- Gaines, Steven (1986). Heroes and Villains: The True Story of The Beach Boys. New York: Da Capo Press. ISBN 0306806479.

- Graff, Gary; Durchholz, Daniel, eds. (1999). MusicHound Rock: The Essential Album Guide. Visible Ink Press. ISBN 1-57859-061-2.

- Highwater, Jamake (1968). Rock and Other Four Letter Words: Music of the Electric Generation. Bantam Books. ISBN 0-552-04334-6.

- Lachman, Gary (2001). Turn Off Your Mind: The Mystic Sixties and the Dark Side of the Age of Aquarius. New York City: The Disinformation Company. ISBN 0-9713942-3-7.

- Larkin, Colin, ed. (2006). The Encyclopedia of Popular Music (4th ed.). London: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-531373-4.

- Love, Mike (2016). Good Vibrations: My Life as a Beach Boy. Penguin Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-698-40886-9.

- Matijas-Mecca, Christian (2017). The Words and Music of Brian Wilson. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-4408-3899-6.

- Mojo, ed. (2007). “The Beach Boys: Friends”. The Mojo Collection: 4th Edition. Canongate Books. ISBN 978-1-84767-643-6.

- Morgan, Johnny (2015). The Beach Boys: America’s Band. New York, NY: Sterling. ISBN 978-1-4549-1709-0.

- Schinder, Scott (2007). “The Beach Boys”. In Schinder, Scott; Schwartz, Andy (eds.). Icons of Rock: An Encyclopedia of the Legends Who Changed Music Forever. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0313338458.

- Shumsky, Susan (2018). Maharishi & Me: Seeking Enlightenment with the Beatles’ Guru. Skyhorse. ISBN 978-1-5107-2268-2.

- Stebbins, Jon (2011). The Beach Boys FAQ: All That’s Left to Know About America’s Band. Backbeat Books. ISBN 978-1-4584-2914-8.

- White, Timothy (1996). The Nearest Faraway Place: Brian Wilson, the Beach Boys, and the Southern Californian Experience. Macmillan. ISBN 0333649370.

- Wilson, Brian; Greenman, Ben (2016). I Am Brian Wilson: A Memoir. Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-0-306-82307-7.

External links

[edit]

- The Beach Boys albums

- Capitol Records albums

- 1968 albums

- Lo-fi music albums

- Albums produced by the Beach Boys

- Albums recorded in a home studio

Main menu

Personal tools

Contents

hide

- (Top)

- Background

- Recording history

- Music and lyrics

- ContentToggle Content subsection

- Maharishi tour

- Sleeve design

- Release

- Critical receptionToggle Critical reception subsection

- Legacy

- Track listingToggle Track listing subsection

- Personnel

- Charts

- Notes

- References

- Bibliography

- External links

Friends (The Beach Boys album)

15 languages

Tools

Appearancehide

Text

- SmallStandardLarge

Width

- StandardWide

Color (beta)

- AutomaticLightDarkReport an issue with dark mode

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Friends | |

|---|---|

| Studio album by the Beach Boys | |

| Released | June 24, 1968 |

| Recorded | February – April 12, 1968 |

| Studio | Beach Boys and ID Sound, Los Angeles |

| Genre | Pop[1]lo-fi[2] |

| Length | 25:32 |

| Label | Capitol |

| Producer | The Beach Boys |

| The Beach Boys chronology | |

| Wild Honey (1967)Friends (1968)The Best of the Beach Boys Vol. 3 (1968) | |

| Singles from Friends | |

| “Friends” / “Little Bird“ Released: April 8, 1968 | |

Friends is the fourteenth studio album by the American rock band the Beach Boys, released on June 24, 1968, through Capitol Records. The album is characterized by its calm and peaceful atmosphere, which contrasted the prevailing music trends of the time, and by its brevity, with five of its 12 tracks running less than two minutes long. It sold poorly, peaking at number 126 on the Billboard charts, the group’s lowest U.S. chart performance to date, although it reached number 13 in the UK. Fans generally came to regard the album as one of the band’s finest.[3]

As with their two previous albums, Friends was recorded primarily at Brian Wilson’s home with a lo-fi production style. The album’s sessions lasted from February to April 1968 at a time when the band’s finances were rapidly diminishing. Despite crediting production to “the Beach Boys”, Wilson actively led the entire project, later referring to it as his second unofficial solo album (the first being 1966’s Pet Sounds). Some of the songs were inspired by the group’s recent involvement with Maharishi Mahesh Yogi and his Transcendental Meditation practice. It was the first album to feature songs from Dennis Wilson.

One single was issued from the album: “Friends“, a waltz that reached number 47 in the U.S. and number 25 in the UK. Its B-side was the Dennis co-write “Little Bird“. In May, the group scheduled a national tour with the Maharishi, but it was canceled after five shows due to low ticket sales and the Maharishi’s subsequent withdrawal. A standalone single, “Do It Again“, was released in July. It reached the U.S. top twenty, became their second number one hit in the UK, and was included in foreign pressings of Friends.

Friends received favorable reviews in the music press, but like their records since Smiley Smile (1967), the album’s simplicity divided critics and fans. Despite the failure of a collaborative tour with the Maharishi, the group remained supporters of him and his teachings. Dennis contributed more songs on later Beach Boys albums, eventually culminating in a solo record, 1977’s Pacific Ocean Blue. In 2018, session highlights, outtakes, and alternate takes were released for the compilation Wake the World: The Friends Sessions.

Background

[edit]

In September and December 1967, the Beach Boys released Smiley Smile and Wild Honey, respectively. Music fans were generally disappointed that the band twice failed to deliver on the hype surrounding their unreleased album Smile, which was advertised as the follow-up to the sophistication of Pet Sounds and “Good Vibrations” (both 1966). Instead, the group were making a deliberate choice to produce music that was simpler and less refined.[4] Commenting on Wild Honey, Mike Love said the band made a conscious decision to be “completely out of the mainstream for what was going on at that time, which was all hard rock/psychedelic music. [The album] just didn’t have anything to do with what was going on.”[5]

Although Wild Honey charted higher than Smiley Smile in the US, it was ultimately the group’s lowest-selling album to that point.[4] Apart from a two-week U.S. tour in November 1967,[6] the band was not performing live during this period, and their finances were rapidly diminishing.[7] That same month, the group stopped wearing their longtime striped-shirt stage uniforms in favor of matching white, polyester suits that were similar to a Las Vegas show band.[8][nb 1]

Dennis Wilson, Al Jardine, and Mike Love were among the many rock musicians who discovered the teachings of Maharishi Mahesh Yogi following the Beatles‘ public endorsement of his Transcendental Meditation technique in August 1967.[10] In December, the touring group attended a lecture by the Maharishi at a UNICEF Variety Gala in Paris[10] and were moved by the simplicity and effectiveness of his meditation process as a means to obtaining inner peace.[11] They were invited to meet the Maharishi in his hotel room the same day, and according to Brian, “they came back and [Carl was] just floating. … it got to me through him.”[12][nb 2] He recalled that he had “already been initiated” beforehand, but “for some ridiculous reason I hadn’t followed through with it, and when you don’t follow through with something you can get all clogged up. … we’re all meditating together now.”[12]

In a January 1968 interview, Brian stated that the group was unsure what their next production would be, but that “it won’t be very long now until I come up with a song about meditation. It shouldn’t be more than a month.”[12] He also expressed an interest in “pull[ing] out of conventional sound making and get[ting] into sounds that have never been made before ever.”[12] In early February, the group performed scattered gigs in the U.S. with Buffalo Springfield.[13] The Beach Boys attended the Maharishi’s public appearances in New York[14] and Cambridge, Massachusetts, after which he invited Love to join the Beatles at his training seminar in Rishikesh in northern India.[15] Love stayed there from February 28 to March 15.[14] In his absence, the rest of the group began recording the album that would become Friends.[16]

Recording history

[edit]

Friends was recorded primarily at the Beach Boys’ private studio, located within Brian’s Bel Air home, from late February to early April 1968.[17] It was written, performed, or produced mainly by the Wilson brothers with what Stebbins terms “a strong assist” from Al Jardine.[18] Jardine remembered how he still “felt that [Brian] had a lot to offer. … We wrote [most of the Friends music] at his house right under that beautiful stained glass Wild Honey cover window.”[19] He added: “We’d get together in the morning. A lot of activity took place in the kitchen. … We were in there as much as in the studio. God, we ate well.”[20]

It was the first Beach Boys album not to have Brian consistently as primary composer,[9] and the first to feature significant songwriting contributions from other group members.[21] Asked as to the level of Wilson’s input, band archivists Mark Linett and Alan Boyd said that Wilson led the entire project, even on the songs that he did not compose.[22] In a 1976 interview, Wilson referred to Friends as his second “solo album”, the first being Pet Sounds.[23] Stephen Desper was recruited as the band’s recording engineer, a role he would keep until 1972.[24] He had been recently contacted to convert Brian’s semi-portable home recording set-up to a more permanent “full-fledged recording studio with the capacity of any other”.[25] Session musicians were used more than on Smiley Smile and Wild Honey, but in smaller configurations than on the Beach Boys’ records from 1962 through 1966.[26]

From February 20 or 27 to March 15, the band tracked “Little Bird“, “Be Here in the Mornin'”, and “Friends”. After Love returned from his retreat, they began recording “When a Man Needs a Woman”, “Passing By”, “Busy Doin’ Nothin’“, “Wake the World“, “Meant for You”, “Anna Lee, the Healer”, and “Be Still”.[27][nb 3] By the spring of 1968, the Beach Boys were overdue to submit an album to Capitol, and so Brian rushed to finish the Friends album while his bandmates were on tour.[22] Sessions concluded with “Diamond Head” on April 12.[27] Desper mixed the album for stereo.[29] It was the band’s first album to be mixed and released exclusively in true stereo, as the band’s releases since The Beach Boys Today! (1965) had only been available in mono or Duophonic.[9]

Music and lyrics

[edit]

The LP has a relatively short length; only two of its 12 tracks last longer than three minutes, and five run short of two minutes.[24] In author Jon Stebbins‘ description, the album “reflects the peaceful and quietly centered aura” that the band had gained from their introduction to Transcendental Meditation.[18] Bruce Johnston described the album as a conscious attempt to make something “really subtle … that wasn’t concerned with radio”.[30] Retrospectively, the album may be viewed as the final installment in a consecutive three-part series of lo-fi Beach Boys albums.[2] Columnist Joel Goldenburg believes that the lightly produced album was the closest the group ever came to sunshine pop, a genre they had influenced but never fully embraced.[31]

For the album’s 1990 CD liner notes, Brian recalled that he “had a good thing rollin’ in my head. The bad things that had happened to me had taken their toll and I was free to find out just how much I had grown through the emotional pain that had come my way. … I think that the Beach Boys’ sound was evolving right along.”[21][nb 4] The few tracks where he served as primary author contained his usual composing trademarks, such as unexpected harmonic changes, descending stepwise progressions, and unusually structured musical phrases.[24] As on much of his compositions of the period, there was a heavy influence drawn from Burt Bacharach.[22]

Subject matter ranges from Transcendental Meditation to bearing children and “doin’ nothin'”.[32] Rolling Stone‘s Jim Miller characterized Friends as a “return to Smiley‘s dryness, minus the weirdness”. Musicologist Daniel Harrison said Miller’s observation was only true of “Meant for You”, and that the remaining songs “have few of the formal or harmonic quirks of the earlier album, though there is no lack of clever and interesting effects, such as the bass harmonica line in ‘Passing By’ or the repetitive monophonic organ line in the break of ‘Be Here in the Morning.'”[33] The group’s influences, according to rock critic Gene Sculatti, seemed to derive “primarily from Pet Sounds, Smiley Smile, Wild Honey, and little else. The characteristic innocence and somewhat childlike visions imparted to their music are applied directly to the theme of the album: friendships. As usual, the lyrics tend to be basic, yet as expressive as they need to be; words, like individual voices or instruments, are all part of the larger whole of music”.[34]

Johnston was unhappy with the group’s “wimpy” songs and opined that the new material—with the sole exception of the title track—did not represent Brian “at full strength”.[35] When asked why the band did not pursue harder rock styles, Jardine responded that “for Carl and me, we were painting a canvas. Jimi [Hendrix] was one of the best in the world, but they were more of a performance phenomenon, representing an era. … We didn’t have that need, because I think it’s a need.”[36] Brian similarly felt no pressure to make “heavy” music: “We never needed to. It’s already been done.”[37]

Content

[edit]

Side one

[edit]

“Meant for You” is a 38-second introduction to the album and the shortest song in the group’s catalog.[38] It was originally conceived as “You’ll Find it Too”,[39] with a longer runtime of about two minutes, and featured additional lyrics about a pony and a puppy.[40][nb 5]

The album’s title track was arranged in 3/4 time after Brian realized that waltzes were uncommon on the radio.[41]

Problems playing this file? See media help.

“Friends” is a waltz that was originally composed in 4/4 time.[41] The song was arranged and co-written by Brian,[21] who described it as his favorite on the album.[42] “Wake the World” was the first original songwriting collaboration between Brian and Jardine. It was another song that Brian said was “my favorite cut [on the album]. It was so descriptive to how I felt about the dramatic change over from day to night.”[21] The song is the first on the album that demonstrates his then-recent “a-day-in-a-life-of” songwriting habit.[43][nb 6]

“Be Here in the Mornin”” and “When a Man Needs a Woman” were written about some particular comforts of Brian’s daily life.[24] The former is another waltz[24] and features the Wilsons’ father Murry contributing a bass vocal.[45] The song makes a passing lyrical reference to the Wilsons’ cousin Steve Korthof, road manager Jon Parks, and Beach Boys manager Nick Grillo.[21] Parks and Korthof themselves shared a writing credit on “When a Man Needs a Woman”.[19] The song was inspired by Marilyn Wilson‘s pregnancy with her and Brian’s first child Carnie, although the lyric suggests that Brian thought it would be a boy.[13]

“Passing By” is wordless, with the melody hummed by Brian.[46] The piece had discarded lyrics written for it: “While walking down the avenue / I stopped to have a look at you / And then I saw / You were just passing by”.[21]

Side two

[edit]

“Anna Lee, the Healer” is about a masseuse Mike Love encountered in Rishikesh.[47] The arrangement consists only of vocals, piano, bass, and hand drumming.[48]

“Little Bird” was composed by Dennis Wilson with poet Stephen Kalinich, which Brian said “blew my mind because it was so full of spiritualness. He was a late bloomer as a music maker. He lived hard and rough but his music was as sensitive as anyone’s.”[21] The bridge section incorporates elements of “Child Is Father of the Man“, a then-unreleased song from Smile.[2] According to Kalinich, Brian composed virtually the entirety of “Little Bird”, but chose not to receive an official writing credit.[49]

“Be Still”, another Dennis/Kalinich song, only features Dennis’ singing[50] and Brian playing organ.[2] Biographer Peter Ames Carlin compared the song to a “Unitarian hymn” and interpreted the lyrics to be a description of “the sacred essence of life and the human potential to interact with God.”[51]

The lyrics of “Busy Doin’ Nothin’” reflect the minutiae of Wilson’s daily social and business life, while the music, he said, was inspired by “bossa nova in general”.[52]

Problems playing this file? See media help.

The final three tracks are genre experiments[48] that break stylistically from the rest of the album.[47] “Busy Doin’ Nothin’” is a flirtation with bossa nova, one of several autobiographic slice-of-life songs written by Brian during this era, and one of the only tracks on the album where he exclusively used session musicians.[21] The lyrics contain step-by-step instructions on how to find his house, albeit without mentioning where to start: “Drive for a couple miles / You’ll see a sign and turn left / For a couple blocks … “[53]

“Diamond Head” is an instrumental exotica lounge jam[47] that echoed the use of extended forms from Smile,[46] and is the album’s longest piece at 3 minutes and 39 seconds.[47] Biographer Mark Dillon surmised that it was likely inspired by the group’s visit to Hawaii during the previous year.[46]

“Transcendental Meditation” contrasts all that comes before it with its raucous tone.[47] Asked about the song, Dennis explained that the group “wanted to get away from anything that sounded too pompous, too religious. It would have been easy to do something peaceful, very Eastern, but we were trying to reach listeners on all levels.”[54] Jardine viewed it as a weak effort.[20]

Leftover

[edit]

Leftover tracks from the sessions include “Untitled #1”, “Away”, “Our New Home” (or “Our Happy Home”), “New Song” (unofficially known as “Spanish Guitar”), “You’re As Cool As Can Be”, covers of Burt Bacharach and Hal David‘s “My Little Red Book” and Buffalo Springfield’s “Rock & Roll Woman“, a demo for “Time to Get Alone“, and an early version of “All I Wanna Do“.[27] “Our Happy Home” was described by music journalist Brian Chidester as “a short, bouncy riff that maintains the gentle air of the Friends sessions”.[2] It was later reworked as “Our Sweet Love” for their 1970 album Sunflower, along with “All I Wanna Do”.[55] “New Song” contains a melody that was recycled for “Transcendental Meditation”. “You’re As Cool As Can Be” is an instrumental of unknown authorship that features an upbeat piano melody played by Brian.[2] “Away” was a song Dennis wrote with touring musician Billy Hinsche in December 1967.[56]

Maharishi tour

[edit]

Main article: The Beach Boys’ 1968 US tour with Maharishi Mahesh Yogi

On April 5, 1968,[27] the band began “the Million Dollar Tour”, a series of self-financed concerts across the American south.[57] Featuring Buffalo Springfield and Strawberry Alarm Clock as supporting acts,[27][58] these shows were poorly attended due in part to the political mood following the assassination of Martin Luther King that April.[16] Six of the 35 dates were canceled, while two were rescheduled.[27] They lost $350,000 in expected revenue (equivalent to $3.07 million in 2023).[59] Mike Love arranged that the group tour the U.S. with the Maharishi in May. According to Nick Grillo, the band hoped that touring with the Maharishi would recuperate some of their financial losses.[60] The Beatles also became disenchanted with the Maharishi and the Spiritual Regeneration Movement and publicly expressed their concerns around this time, which had a detrimental effect on the guru’s standing among music fans. In Stebbins’ description, the Maharishi became a pariah.[61]

The shows with the Maharishi were advertised as “The Most Exciting Event of the Decade!” and comprised a set of songs by the Beach Boys followed by the Maharishi’s lecture on the benefits of meditation.[62] The tour started on May 3 and ended abruptly after five shows. A performance at the Singer Bowl in Queens, New York was canceled twenty minutes before the group were scheduled to perform when only 800 people showed up to the 16,000-capacity venue.[63] Writing in New York magazine, Loraine Alterman reported on the hostile audience reaction to the Maharishi but said that the songs the band included from Friends worked well beside the group’s previous hits “because they were happy and full of love”. She added that, unlike the Maharishi’s lecture, the song “Transcendental Meditation” “did not tax anyone’s brain. It just repeated how transcendental meditation ‘makes you feel grand’ against a moving beat.”[64]

Because of the disappointing audience numbers and the Maharishi’s subsequent withdrawal to fulfill film contracts, the remaining 24 tour dates were canceled at a cost estimated at $250,000 for the band (equivalent to $2.19 million in 2023).[7] Afterward, Love and Carl told journalists that the racial violence following King’s assassination was to blame for the tour’s demise. Carl said: “A lot of people just would not let their children out. Nobody wants to get hurt.” He added that the group’s goal was to appeal mainly to young people, “but not the teeny-boppers“, while Love commented that the shows were “not put together for commercial purposes”.[65] In his 2016 autobiography, Love wrote: “I take responsibility for an idea that didn’t work. But I don’t regret it. I thought I could do some good for people who were lost, confused, or troubled, particularly those who were young and idealistic but also vulnerable, and I thought that was true for a whole bunch of us.”[66][nb 7]

Sleeve design

[edit]

Friends was packaged with a cover artwork, designed by David McMacken, that depicted the band members in a psychedelic visual style.[68] Love remembered that the group lacked “savvy marketing and design”, and that while in Rishikesh, Paul McCartney had urged him “to take more care of what you put on your album covers”.[69] Johnston opined that the Friends cover ultimately ranked second to Pet Sounds for being the worst “in the history of the music business”.[35] Matijas-Mecca said the artwork “did nothing to convince anyone that the Beach Boys were in touch with anything in particular”.[17]

Release

[edit]

Friends came out just after Hendrix and Cream. The whole country had discovered drugs, discovered words, discovered Marshall amplifiers, and here comes this feather floating through a wall of noise.

—Bruce Johnston, 2007[30]

Lead single “Friends” was issued on April 8 and reached number 47 on the Billboard Hot 100,[18] making it their lowest-charting single in six years.[30] On June 4, the Beach Boys appeared on The Les Crane Show and discussed their support of the Maharishi.[70][nb 8] The Friends album followed on June 24.[50]

On July 2, the group embarked on a three-week U.S. tour with further dates continuing throughout August, including some stops in Canada.[71] Their setlists included “Friends”, “Little Bird”, and “Wake the World”. Several supporting musicians accompanied the group (keyboardist Daryl Dragon, bassist Ed Carter, percussionist Mike Kowalski, and a brass section).[72] Johnston remembered that performing the Friends songs caused him to “wince”, and that it was difficult to maintain the “subtle” nature of the songs in a live setting.[35]

On July 6, Friends debuted on the Billboard Top LPs chart at number 179[73] and subsequently peaked at number 126 while artists such as the Doors and Cream occupied the top positions.[50] On July 8, the band released “Do It Again” as a standalone single backed with “Wake the World”. “Do It Again” was recorded within the prior two months as a self-conscious throwback to the group’s early surf songs, and the first time they had embraced the subject matter since 1964.[74][nb 9] It reached the top twenty in the U.S. and was a number one hit in the UK. When Friends was issued in Japan, the song was included in the album’s track list.[19]

Love recalled that the album’s commercial failure caused Capitol to “panic”.[75] On August 5, the label issued the greatest hits album Best of the Beach Boys Vol. 3 to recuperate from the LP’s poor sales. Matijas-Mecca wrote that this was a sign that the label had “given up” on the group, repeating a tactic they used after the release of Pet Sounds and again with Smiley Smile.[76] While the first two volumes were quickly certified as gold records, biographer David Leaf said that the label was “more than a little horrified to watch [the third volume] sink like a stone, unable to even outperform Friends.”[21] A collection of Beach Boys backing tracks, Stack-o-Tracks, was issued by Capitol on August 19. The album became the first Beach Boys LP that failed to chart in the U.S. and UK.[77] Friends ended its 10-week stay on the Billboard charts on September 7.[21] Ultimately, the album’s record sales in the U.S. (estimated at 18,000 units)[78] were the group’s worst to date.[21] In the UK, the album fared better, reaching number 13 on the UK Albums Chart.[21]

Critical reception

[edit]

Contemporary

[edit]