JOHN LENNON

Main menu

Personal tools

Contents

hide

- (Top)

- Early years: 1940–1956

- The Quarrymen to the Beatles: 1956–1970Toggle The Quarrymen to the Beatles: 1956–1970 subsection

- Solo career: 1970–1980Toggle Solo career: 1970–1980 subsection

- Murder

- Personal relationshipsToggle Personal relationships subsection

- Political activismToggle Political activism subsection

- Writing

- Art

- MusicianshipToggle Musicianship subsection

- LegacyToggle Legacy subsection

- DiscographyToggle Discography subsection

- FilmographyToggle Filmography subsection

- Bibliography

- See also

- Notes

- ReferencesToggle References subsection

- Further reading

- External links

John Lennon

137 languages

Tools

Appearancehide

Text

- SmallStandardLarge

Width

- StandardWide

Color (beta)

- AutomaticLightDark

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

“Lennon” redirects here. For other uses, see Lennon (disambiguation) and John Lennon (disambiguation).

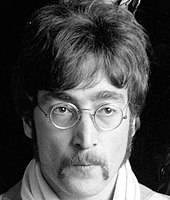

| John Lennon | |

|---|---|

| Lennon in 1974 | |

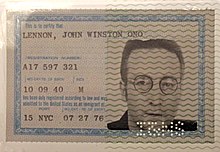

| Born | John Winston Lennon 9 October 1940 Liverpool, England |

| Died | 8 December 1980 (aged 40) New York City, US |

| Cause of death | Murder by shooting |

| Resting place | Cremated; ashes scattered in Central Park, New York City |

| Other names | John Winston Ono Lennon |

| Occupations | Singersongwritermusicianauthorartist[1]peace activist |

| Years active | 1956–1980 |

| Spouses | Cynthia Powell(m.1962; div.1968)Yoko Ono (m.1969) |

| Partner | May Pang (1973–1975) |

| Children | JulianSean |

| Parents | Alfred Lennon (father)Julia Stanley (mother) |

| Relatives | Julia Baird (half-sister)Mimi Smith (aunt) |

| Musical career | |

| Genres | Rockpopexperimental |

| Instruments | Vocalsguitarkeyboardsharmonica |

| Labels | ParlophoneCapitolAppleGeffenPolydor |

| Formerly of | The QuarrymenThe BeatlesThe Dirty MacPlastic Ono Band |

| Website | johnlennon.com |

| Signature | |

John Winston Ono Lennon[nb 1] (born John Winston Lennon; 9 October 1940 – 8 December 1980) was an English singer, songwriter and musician. He gained worldwide fame as the founder, co-lead vocalist and rhythm guitarist of the Beatles. His work included music, writing, drawings and film. His songwriting partnership with Paul McCartney remains the most successful in history as the primary songwriters in the Beatles.[3]

Born in Liverpool, Lennon became involved in the skiffle craze as a teenager. In 1956, he formed the Quarrymen, which evolved into the Beatles in 1960. Sometimes called “the smart Beatle”, Lennon initially was the group’s de facto leader, a role he gradually seemed to cede to McCartney. Through his songwriting in the Beatles, he embraced myriad musical influences, initially writing and co-writing rock and pop-oriented hit songs in the band’s early years, then later incorporating experimental elements into his compositions in the latter half of the Beatles’ career as his songs became known for their increasing innovation. Lennon soon expanded his work into other media by participating in numerous films, including How I Won the War, and authoring In His Own Write and A Spaniard in the Works, both collections of nonsense writings and line drawings. Starting with “All You Need Is Love“, his songs were adopted as anthems by the anti-war movement and the larger counterculture of the 1960s. In 1969, he started the Plastic Ono Band with his second wife, multimedia artist Yoko Ono, held the two-week-long anti-war demonstration bed-in for peace, and left the Beatles to embark on a solo career.

Lennon and Ono collaborated on many works, including a trilogy of avant-garde albums and several more films. After the Beatles disbanded, Lennon released his solo debut John Lennon/Plastic Ono Band and the international top-10 singles “Give Peace a Chance“, “Instant Karma!“, “Imagine“, and “Happy Xmas (War Is Over)“. Moving to New York City in 1971, his criticism of the Vietnam War resulted in a three-year deportation attempt by the Nixon administration. Lennon and Ono separated from 1973 to 1975, during which time he produced Harry Nilsson‘s album Pussy Cats. He also had chart-topping collaborations with Elton John (“Whatever Gets You thru the Night“) and David Bowie (“Fame“). Following a five-year hiatus, Lennon returned to music in 1980 with the Ono collaboration Double Fantasy. He was murdered by a Beatles fan, Mark David Chapman, three weeks after the album’s release.

As a performer, writer or co-writer, Lennon had 25 number-one singles in the Billboard Hot 100 chart. Double Fantasy, his second-best-selling non-Beatles album, won the 1981 Grammy Award for Album of the Year.[4] That year, he won the Brit Award for Outstanding Contribution to Music. In 2002, Lennon was voted eighth in a BBC history poll of the 100 Greatest Britons. Rolling Stone ranked him the fifth-greatest singer and 38th greatest artist of all time. He was inducted into the Songwriters Hall of Fame (in 1997) and the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame (twice, as a member of the Beatles in 1988 and as a solo artist in 1994).

Early years: 1940–1956

John Winston Lennon was born on 9 October 1940 at Liverpool Maternity Hospital, the only child of Julia (née Stanley) (1914–1958) and Alfred Lennon (1912–1976). Alfred was a merchant seaman of Irish descent who was away at the time of his son’s birth.[5] His parents named him John Winston Lennon after his paternal grandfather, John “Jack” Lennon, and Prime Minister Winston Churchill.[6] His father was often away from home but sent regular pay cheques to 9 Newcastle Road, Liverpool, where Lennon lived with his mother;[7] the cheques stopped when he went absent without leave in February 1944.[8][9] When he eventually came home six months later, he offered to look after the family, but Julia, by then pregnant with another man’s child, rejected the idea.[10] After her sister Mimi complained to Liverpool’s Social Services twice, Julia gave her custody of Lennon.

In July 1946, Lennon’s father visited her and took his son to Blackpool, secretly intending to emigrate to New Zealand with him.[11] Julia followed them – with her partner at the time, Bobby Dykins – and after a heated argument, his father forced the five-year-old to choose between them. In one account of this incident, Lennon twice chose his father, but as his mother walked away, he began to cry and followed her.[12] According to author Mark Lewisohn, however, Lennon’s parents agreed that Julia should take him and give him a home. Billy Hall, who witnessed the incident, has said that the dramatic portrayal of a young John Lennon being forced to make a decision between his parents is inaccurate.[13] Lennon had no further contact with Alf for close to 20 years.[14]

Throughout the rest of his childhood and adolescence, Lennon lived at Mendips, 251 Menlove Avenue, Woolton, with Mimi and her husband George Toogood Smith, who had no children of their own.[15] His aunt purchased volumes of short stories for him, and his uncle, a dairyman at his family’s farm, bought him a mouth organ and engaged him in solving crossword puzzles.[16] Julia visited Mendips on a regular basis, and John often visited her at 1 Blomfield Road, Liverpool, where she played him Elvis Presley records, taught him the banjo, and showed him how to play “Ain’t That a Shame” by Fats Domino.[17] In September 1980, Lennon commented about his family and his rebellious nature:

A part of me would like to be accepted by all facets of society and not be this loudmouthed lunatic poet/musician. But I cannot be what I am not … I was the one who all the other boys’ parents – including Paul’s father – would say, “Keep away from him” … The parents instinctively recognised I was a troublemaker, meaning I did not conform and I would influence their children, which I did. I did my best to disrupt every friend’s home … Partly out of envy that I didn’t have this so-called home … but I did … There were five women that were my family. Five strong, intelligent, beautiful women, five sisters. One happened to be my mother. [She] just couldn’t deal with life. She was the youngest and she had a husband who ran away to sea and the war was on and she couldn’t cope with me, and I ended up living with her elder sister. Now those women were fantastic … And that was my first feminist education … I would infiltrate the other boys’ minds. I could say, “Parents are not gods because I don’t live with mine and, therefore, I know.”[18]

He regularly visited his cousin Stanley Parkes, who lived in Fleetwood and took him on trips to local cinemas.[19] During the school holidays Parkes often visited Lennon with Leila Harvey, another cousin, and the three often travelled to Blackpool two or three times a week to watch shows. They would visit the Blackpool Tower Circus and see artists such as Dickie Valentine, Arthur Askey, Max Bygraves and Joe Loss, with Parkes recalling that Lennon particularly liked George Formby.[20] After Parkes’s family moved to Scotland, the three cousins often spent their school holidays together there. Parkes recalled, “John, cousin Leila and I were very close. From Edinburgh we would drive up to the family croft at Durness, which was from about the time John was nine years old until he was about 16.”[21] Lennon’s uncle George died of a liver haemorrhage on 5 June 1955, aged 52.[22]

Lennon was raised as an Anglican and attended Dovedale Primary School.[23] After passing his eleven-plus exam, he attended Quarry Bank High School in Liverpool from September 1952 to 1957, and was described by Harvey at the time as a “happy-go-lucky, good-humoured, easy going, lively lad”.[24] However, he was also known to frequently engage in fights, bully and disrupt classes.[25] Despite this, he quickly built a reputation as the class clown[26] and often drew comical cartoons that appeared in his self-made school magazine, the Daily Howl.[27][nb 2]

In 1956, Julia bought John his first guitar. The instrument was an inexpensive Gallotone Champion acoustic for which she lent her son five pounds and ten shillings on the condition that the guitar be delivered to her own house and not Mimi’s, knowing well that her sister was not supportive of her son’s musical aspirations.[29] Mimi was sceptical of his claim that he would be famous one day, and she hoped that he would grow bored with music, often telling him, “The guitar’s all very well, John, but you’ll never make a living out of it.”[30]

Lennon’s senior school years were marked by a shift in his behaviour. Teachers at Quarry Bank High School described him thus: “He has too many wrong ambitions and his energy is often misplaced”, and “His work always lacks effort. He is content to ‘drift’ instead of using his abilities.”[31] Lennon’s misbehaviour created a rift in his relationship with his aunt.

On 15 July 1958, at the age of 44, Julia Lennon was struck and killed by a car while she was walking home after visiting the Smiths’ house.[32] His mother’s death traumatised the teenage Lennon, who, for the next two years, drank heavily and frequently got into fights, consumed by a “blind rage”.[33] Julia’s memory would later serve as a major creative inspiration for Lennon, inspiring songs such as the 1968 Beatles song “Julia“.[34]

Lennon failed his O-level examinations, and was accepted into the Liverpool College of Art after his aunt and headmaster intervened.[35] At the college he began to wear Teddy Boy clothes and was threatened with expulsion for his behaviour.[36] In the description of Cynthia Powell, Lennon’s fellow student and subsequently his wife, he was “thrown out of the college before his final year”.[37]

The Quarrymen to the Beatles: 1956–1970

Further information: The Quarrymen, Lennon–McCartney, The Beatles, Beatlemania, British Invasion, and More popular than Jesus

Formation, fame and touring: 1956–1966

At the age of 15, Lennon formed a skiffle group, the Quarrymen. Named after Quarry Bank High School, the group was established by Lennon in September 1956.[38] By the summer of 1957, the Quarrymen played a “spirited set of songs” made up of half skiffle and half rock and roll.[39] Lennon first met Paul McCartney at the Quarrymen’s second performance, which was held in Woolton on 6 July at the St Peter’s Church garden fête. Lennon then asked McCartney to join the band.[40]

McCartney said that Aunt Mimi “was very aware that John’s friends were lower class”, and would often patronise him when he arrived to visit Lennon.[41] According to McCartney’s brother Mike, their father similarly disapproved of Lennon, declaring that Lennon would get his son “into trouble”.[42] McCartney’s father nevertheless allowed the fledgling band to rehearse in the family’s front room at 20 Forthlin Road.[43][44] During this time Lennon wrote his first song, “Hello Little Girl“, which became a UK top 10 hit for the Fourmost in 1963.[45]

McCartney recommended that his friend George Harrison become the lead guitarist.[46] Lennon thought that Harrison, then 14 years old, was too young. McCartney engineered an audition on the upper deck of a Liverpool bus, where Harrison played “Raunchy” for Lennon and was asked to join.[47] Stuart Sutcliffe, Lennon’s friend from art school, later joined as bassist.[48] Lennon, McCartney, Harrison and Sutcliffe became “The Beatles” in early 1960. In August that year, the Beatles were engaged for a 48-night residency in Hamburg, in West Germany, and were desperately in need of a drummer. They asked Pete Best to join them.[49] Lennon’s aunt, horrified when he told her about the trip, pleaded with Lennon to continue his art studies instead.[50] After the first Hamburg residency, the band accepted another in April 1961, and a third in April 1962. As with the other band members, Lennon was introduced to Preludin while in Hamburg,[51] and regularly took the drug as a stimulant during their long, overnight performances.[52]

Brian Epstein managed the Beatles from 1962 until his death in 1967. He had no previous experience managing artists, but he had a strong influence on the group’s dress code and attitude on stage.[53] Lennon initially resisted his attempts to encourage the band to present a professional appearance, but eventually complied, saying “I’ll wear a bloody balloon if somebody’s going to pay me.”[54] McCartney took over on bass after Sutcliffe decided to stay in Hamburg, and Best was replaced with drummer Ringo Starr; this completed the four-piece line-up that would remain until the group’s break-up in 1970. The band’s first single, “Love Me Do“, was released in October 1962 and reached No. 17 on the British charts. They recorded their debut album, Please Please Me, in under 10 hours on 11 February 1963,[55] a day when Lennon was suffering the effects of a cold,[56] which is evident in the vocal on the last song to be recorded that day, “Twist and Shout“.[57] The Lennon–McCartney songwriting partnership yielded eight of its fourteen tracks. With a few exceptions, one being the album title itself, Lennon had yet to bring his love of wordplay to bear on his song lyrics, saying: “We were just writing songs … pop songs with no more thought of them than that – to create a sound. And the words were almost irrelevant”.[55] In a 1987 interview, McCartney said that the other Beatles idolised Lennon: “He was like our own little Elvis … We all looked up to John. He was older and he was very much the leader; he was the quickest wit and the smartest.”[58]

The Beatles achieved mainstream success in the UK early in 1963. Lennon was on tour when his first son, Julian, was born in April. During their Royal Variety Show performance, which was attended by the Queen Mother and other British royalty, Lennon poked fun at the audience: “For our next song, I’d like to ask for your help. For the people in the cheaper seats, clap your hands … and the rest of you, if you’ll just rattle your jewellery.”[59] After a year of Beatlemania in the UK, the group’s historic February 1964 US debut appearance on The Ed Sullivan Show marked their breakthrough to international stardom. A two-year period of constant touring, filmmaking, and songwriting followed, during which Lennon wrote two books, In His Own Write and A Spaniard in the Works.[60] The Beatles received recognition from the British establishment when they were appointed Members of the Order of the British Empire (MBE) in the 1965 Queen’s Birthday Honours.[61]

Lennon grew concerned that fans who attended Beatles concerts were unable to hear the music above the screaming of fans, and that the band’s musicianship was beginning to suffer as a result.[62] Lennon’s “Help!” expressed his own feelings in 1965: “I meant it … It was me singing ‘help'”.[63] He had put on weight (he would later refer to this as his “Fat Elvis” period),[64] and felt he was subconsciously seeking change.[65] In March that year he and Harrison were unknowingly introduced to LSD when a dentist, hosting a dinner party attended by the two musicians and their wives, spiked the guests’ coffee with the drug.[66] When they wanted to leave, their host revealed what they had taken, and strongly advised them not to leave the house because of the likely effects. Later, in a lift at a nightclub, they all believed it was on fire; Lennon recalled: “We were all screaming … hot and hysterical.”[67]

In March 1966, during an interview with Evening Standard reporter Maureen Cleave, Lennon remarked, “Christianity will go. It will vanish and shrink … We’re more popular than Jesus now – I don’t know which will go first, rock and roll or Christianity.”[68] The comment went virtually unnoticed in England but caused great offence in the US when quoted by a magazine there five months later. The furore that followed, which included the burning of Beatles records, Ku Klux Klan activity and threats against Lennon, contributed to the band’s decision to stop touring.[69]

Studio years, break-up and solo work: 1966–1970

After the band’s final concert on 29 August 1966, Lennon filmed the anti-war black comedy How I Won the War – his only appearance in a non-Beatles feature film – before rejoining his bandmates for an extended period of recording, beginning in November.[70] Lennon had increased his use of LSD[71] and, according to author Ian MacDonald, his continuous use of the drug in 1967 brought him “close to erasing his identity“.[72] The year 1967 saw the release of “Strawberry Fields Forever“, hailed by Time magazine for its “astonishing inventiveness”,[73] and the group’s landmark album Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, which revealed lyrics by Lennon that contrasted strongly with the simple love songs of the group’s early years.[74]

In late June, the Beatles performed Lennon’s “All You Need Is Love” as Britain’s contribution to the Our World satellite broadcast, before an international audience estimated at up to 400 million.[75] Intentionally simplistic in its message,[76] the song formalised his pacifist stance and provided an anthem for the Summer of Love.[77] After the Beatles were introduced to the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, the group attended an August weekend of personal instruction at his Transcendental Meditation seminar in Bangor, Wales.[78] During the seminar, they were informed of Epstein’s death. “I knew we were in trouble then”, Lennon said later. “I didn’t have any misconceptions about our ability to do anything other than play music. I was scared – I thought, ‘We’ve fucking had it now.'”[79] McCartney organised the group’s first post-Epstein project,[80] the self-written, -produced and -directed television film Magical Mystery Tour, which was released in December that year. While the film itself proved to be their first critical flop, its soundtrack release, featuring Lennon’s Lewis Carroll–inspired “I Am the Walrus“, was a success.[81][82]

Led by Harrison and Lennon’s interest, the Beatles travelled to the Maharishi’s ashram in India in February 1968 for further guidance.[83] While there, they composed most of the songs for their double album The Beatles,[84] but the band members’ mixed experience with Transcendental Meditation signalled a sharp divergence in the group’s camaraderie.[85] On their return to London, they became increasingly involved in business activities with the formation of Apple Corps, a multimedia corporation composed of Apple Records and several other subsidiary companies. Lennon described the venture as an attempt to achieve “artistic freedom within a business structure”.[86] Released amid the Protests of 1968, the band’s debut single for the Apple label included Lennon’s B-side “Revolution“, in which he called for a “plan” rather than committing to Maoist revolution. The song’s pacifist message led to ridicule from political radicals in the New Left press.[87] Adding to the tensions at the Beatles’ recording sessions that year, Lennon insisted on having his new girlfriend, the Japanese artist Yoko Ono, beside him, thereby contravening the band’s policy regarding wives and girlfriends in the studio. He was especially pleased with his songwriting contributions to the double album and identified it as a superior work to Sgt. Pepper.[88] At the end of 1968, Lennon participated in The Rolling Stones Rock and Roll Circus, a television special that was not broadcast. Lennon performed with the Dirty Mac, a supergroup composed of Lennon, Eric Clapton, Keith Richards and Mitch Mitchell. The group also backed a vocal performance by Ono. A film version was released in 1996.[89]

By late 1968, Lennon’s increased drug use and growing preoccupation with Ono, combined with the Beatles’ inability to agree on how the company should be run, left Apple in need of professional management. Lennon asked Lord Beeching to take on the role but he declined, advising Lennon to go back to making records. Lennon was approached by Allen Klein, who had managed the Rolling Stones and other bands during the British Invasion. In early 1969, Klein was appointed as Apple’s chief executive by Lennon, Harrison and Starr[90] but McCartney never signed the management contract.[91]

Lennon and Ono were married on 20 March 1969 and soon released a series of 14 lithographs called “Bag One” depicting scenes from their honeymoon,[92] eight of which were deemed indecent and most of which were banned and confiscated.[93] Lennon’s creative focus continued to move beyond the Beatles, and between 1968 and 1969 he and Ono recorded three albums of experimental music together: Unfinished Music No. 1: Two Virgins[94] (known more for its cover than for its music), Unfinished Music No. 2: Life with the Lions and Wedding Album. In 1969, they formed the Plastic Ono Band, releasing Live Peace in Toronto 1969. Between 1969 and 1970, Lennon released the singles “Give Peace a Chance”, which was widely adopted as an anti-Vietnam War anthem,[95] “Cold Turkey“, which documented his withdrawal symptoms after he became addicted to heroin,[96] and “Instant Karma!“.

Sample of “Give Peace a Chance“, recorded in Montreal in 1969 during Lennon and Ono’s second bed-in. As described by biographer Bill Harry, Lennon wanted to “write a peace anthem that would take over from the song ‘We Shall Overcome‘ – and he succeeded … it became the main anti-Vietnam protest song.”[97]

Problems playing this file? See media help.

In protest at Britain’s involvement in “the Nigeria-Biafra thing”[98] (namely, the Nigerian Civil War),[99] its support of America in the Vietnam War and (perhaps jokingly) against “Cold Turkey” slipping down the charts,[100] Lennon returned his MBE medal to the Queen. This gesture had no effect on his MBE status, which could be renounced but ultimately only the Sovereign has the power to annul the original award.[101][102] The medal, together with Lennon’s letter, is held at the Central Chancery of the Orders of Knighthood.[103]

Lennon left the Beatles on 20 September 1969,[104] but agreed not to inform the media while the group renegotiated their recording contract. He was outraged that McCartney publicised his own departure on releasing his debut solo album in April 1970. Lennon’s reaction was, “Jesus Christ! He gets all the credit for it!”[105] He later wrote, “I started the band. I disbanded it. It’s as simple as that.”[106] In a December 1970 interview with Jann Wenner of Rolling Stone magazine, he revealed his bitterness towards McCartney, saying, “I was a fool not to do what Paul did, which was use it to sell a record.”[107] Lennon also spoke of the hostility he perceived the other members had towards Ono, and of how he, Harrison and Starr “got fed up with being sidemen for Paul … After Brian Epstein died we collapsed. Paul took over and supposedly led us. But what is leading us when we went round in circles?”[108]

Solo career: 1970–1980

Initial solo success and activism: 1970–1972

When it gets down to having to use violence, then you are playing the system’s game. The establishment will irritate you – pull your beard, flick your face – to make you fight. Because once they’ve got you violent, then they know how to handle you. The only thing they don’t know how to handle is non-violence and humor.

Between 1 April and 15 September 1970, Lennon and Ono went through primal therapy with Arthur Janov at Tittenhurst, in London and at Janov’s clinic in Los Angeles, California. Designed to release emotional pain from early childhood, the therapy entailed two half-days a week with Janov for six months; he had wanted to treat the couple for longer, but their American visa ran out and they had to return to the UK.[111] Lennon’s debut solo album, John Lennon/Plastic Ono Band (1970), was received with praise by many music critics, but its highly personal lyrics and stark sound limited its commercial performance.[112] The album featured the song “Mother“, in which Lennon confronted his feelings of childhood rejection,[113] and the Dylanesque “Working Class Hero“, a bitter attack against the bourgeois social system which, due to the lyric “you’re still fucking peasants”, fell foul of broadcasters.[114][115]

In January 1971, Tariq Ali expressed his revolutionary political views when he interviewed Lennon, who immediately responded by writing “Power to the People“. In his lyrics to the song, Lennon reversed the non-confrontational approach he had espoused in “Revolution”, although he later disowned “Power to the People”, saying that it was borne out of guilt and a desire for approval from radicals such as Ali.[116] Lennon became involved in a protest against the prosecution of Oz magazine for alleged obscenity. Lennon denounced the proceedings as “disgusting fascism”, and he and Ono (as Elastic Oz Band) released the single “God Save Us/Do the Oz” and joined marches in support of the magazine.[117]

Sample of “Imagine“, Lennon’s most widely known post-Beatles song.[118] Like “Give Peace a Chance”, the song became an anti-war anthem, but its lyrics offended religious groups. Lennon’s explanation was: “If you can imagine a world at peace, with no denominations of religion – not without religion, but without this ‘my god is bigger than your god’ thing – then it can be true.”[119]

Problems playing this file? See media help.

Eager for a major commercial success, Lennon adopted a more accessible sound for his next album, Imagine (1971).[120] Rolling Stone reported that “it contains a substantial portion of good music” but warned of the possibility that “his posturings will soon seem not merely dull but irrelevant”.[121] The album’s title track later became an anthem for anti-war movements,[122] while the song “How Do You Sleep?” was a musical attack on McCartney in response to lyrics on Ram that Lennon felt, and McCartney later confirmed,[123] were directed at him and Ono.[124][nb 3] In “Jealous Guy“, Lennon addressed his demeaning treatment of women, acknowledging that his past behaviour was the result of long-held insecurity.[126]

In gratitude for his guitar contributions to Imagine, Lennon initially agreed to perform at Harrison’s Concert for Bangladesh benefit shows in New York.[127] Harrison refused to allow Ono to participate at the concerts, however, which resulted in the couple having a heated argument and Lennon pulling out of the event.[128]

Lennon and Ono moved to New York in August 1971 and immediately embraced US radical left politics. The couple released their “Happy Xmas (War Is Over)” single in December.[129] During the new year, the Nixon administration took what it called a “strategic counter-measure” against Lennon’s anti-war and anti-Nixon propaganda. The administration embarked on what would be a four-year attempt to deport him.[130][131] Lennon was embroiled in a continuing legal battle with the immigration authorities, and he was denied permanent residency in the US; the issue would not be resolved until 1976.[132]

Some Time in New York City was recorded as a collaboration with Ono and was released in 1972 with backing from the New York band Elephant’s Memory. A double LP, it contained songs about women’s rights, race relations, Britain’s role in Northern Ireland and Lennon’s difficulties in obtaining a green card.[133] The album was a commercial failure and was maligned by critics, who found its political sloganeering heavy-handed and relentless.[134] The NME‘s review took the form of an open letter in which Tony Tyler derided Lennon as a “pathetic, ageing revolutionary”.[135] In the US, “Woman Is the Nigger of the World” was released as a single from the album and was televised on 11 May, on The Dick Cavett Show. Many radio stations refused to broadcast the song because of the word “nigger“.[136]

Lennon and Ono gave two benefit concerts with Elephant’s Memory and guests in New York in aid of patients at the Willowbrook State School mental facility.[137] Staged at Madison Square Garden on 30 August 1972, they were his last full-length concert appearances.[138] After George McGovern lost the 1972 presidential election to Richard Nixon, Lennon and Ono attended a post-election wake held in the New York home of activist Jerry Rubin.[130] Lennon was depressed and got intoxicated; he left Ono embarrassed after he had sex with a female guest. Ono’s song “Death of Samantha” was inspired by the incident.[139]

“Lost weekend”: 1973–1975

As Lennon was about to record Mind Games in 1973, he and Ono decided to separate. The ensuing 18-month period apart, which he later called his “lost weekend” in reference to the film of the same name,[140][141] was spent in Los Angeles and New York City in the company of May Pang.[142] Mind Games, credited to the “Plastic U.F.Ono Band”, was released in November 1973. Lennon also contributed “I’m the Greatest” to Starr’s album Ringo (1973), released the same month. With Harrison joining Starr and Lennon at the recording session for the song, it marked the only occasion when three former Beatles recorded together between the band’s break-up and Lennon’s death.[143][nb 4]

In early 1974, Lennon was drinking heavily and his alcohol-fuelled antics with Harry Nilsson made headlines. In March, two widely publicised incidents occurred at The Troubadour club. In the first incident, Lennon stuck an unused menstrual pad on his forehead and scuffled with a waitress. The second incident occurred two weeks later, when Lennon and Nilsson were ejected from the same club after heckling the Smothers Brothers.[145] Lennon decided to produce Nilsson’s album Pussy Cats, and Pang rented a Los Angeles beach house for all the musicians.[146] After a month of further debauchery, the recording sessions were in chaos, and Lennon returned to New York with Pang to finish work on the album. In April, Lennon had produced the Mick Jagger song “Too Many Cooks (Spoil the Soup)” which was, for contractual reasons, to remain unreleased for more than 30 years. Pang supplied the recording for its eventual inclusion on The Very Best of Mick Jagger (2007).[147]

Lennon had settled back in New York when he recorded the album Walls and Bridges. Released in October 1974, it included “Whatever Gets You thru the Night“, which featured Elton John on backing vocals and piano, and became Lennon’s only single as a solo artist to top the US Billboard Hot 100 chart during his lifetime.[148][nb 5] A second single from the album, “#9 Dream“, followed before the end of the year. Starr’s Goodnight Vienna (1974) again saw assistance from Lennon, who wrote the title track and played piano.[150] On 28 November, Lennon made a surprise guest appearance at Elton John’s Thanksgiving concert at Madison Square Garden, in fulfilment of his promise to join the singer in a live show if “Whatever Gets You thru the Night”, a song whose commercial potential Lennon had doubted, reached number one. Lennon performed the song along with “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds” and “I Saw Her Standing There“, which he introduced as “a song by an old estranged fiancé of mine called Paul”.[151]

In the first two weeks of January 1975, Elton John topped the US Billboard Hot 100 singles chart with his cover of “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds“, featuring Lennon on guitar and backing vocals – Lennon is credited on the single under the moniker of “Dr. Winston O’Boogie”. As January became February, Lennon and Ono reunited as Lennon and Bowie completed recording of their co-composition “Fame“,[111][152][153][154] which became David Bowie‘s first US number one, featuring guitar and backing vocals by Lennon. In February, Lennon released Rock ‘n’ Roll (1975), an album of cover songs. “Stand by Me“, taken from the album and a US and UK hit, became his last single for five years.[155] He made what would be his final stage appearance in the ATV special A Salute to Lew Grade, recorded on 18 April and televised in June.[156] Playing acoustic guitar and backed by an eight-piece band, Lennon performed two songs from Rock ‘n’ Roll (“Stand by Me”, which was not broadcast, and “Slippin’ and Slidin'”) followed by “Imagine”.[156] The band, known as Etc., wore masks behind their heads, a dig by Lennon, who thought Grade was two-faced.[157]

Hiatus and return: 1975–1980

Sean was Lennon’s only child with Ono. Sean was born on 9 October 1975 (Lennon’s thirty-fifth birthday), and John took on the role of househusband. Lennon began what would be a five-year hiatus from the music industry, during which time, he later said, he “baked bread” and “looked after the baby”.[158] He devoted himself to Sean, rising at 6 am daily to plan and prepare his meals and to spend time with him.[159] He wrote “Cookin’ (In the Kitchen of Love)” for Starr’s Ringo’s Rotogravure (1976), performing on the track in June in what would be his last recording session until 1980.[160] He formally announced his break from music in Tokyo in 1977, saying, “we have basically decided, without any great decision, to be with our baby as much as we can until we feel we can take time off to indulge ourselves in creating things outside of the family.”[161] During his career break he created several series of drawings, and drafted a book containing a mix of autobiographical material and what he termed “mad stuff”,[162] all of which would be published posthumously.

Lennon emerged from his hiatus in October 1980, when he released the single “(Just Like) Starting Over“. In November, he and Ono released the album Double Fantasy, which included songs Lennon had written in Bermuda. In June, Lennon chartered a 43-foot sailboat and embarked on a sailing trip to Bermuda. En route, he and the crew encountered a storm, rendering everyone on board seasick, except Lennon, who took control and sailed the boat through the storm. This experience re-invigorated him and his creative muse. He spent three weeks in Bermuda in a home called Fairylands writing and refining the tracks for the upcoming album.[163][164][165][166]

The music reflected Lennon’s fulfilment in his new-found stable family life.[167] Sufficient additional material was recorded for a planned follow-up album Milk and Honey, which was issued posthumously, in 1984.[168] Double Fantasy was not well received initially and drew comments such as Melody Maker‘s “indulgent sterility … a godawful yawn”.[169]

Murder

Main article: Murder of John Lennon

In New York, at approximately 5:00 p.m. on 8 December 1980, Lennon autographed a copy of Double Fantasy for Mark David Chapman before leaving The Dakota with Ono for a recording session at the Record Plant.[170] After the session, Lennon and Ono returned to the Dakota in a limousine at around 10:50 p.m. (EST). They left the vehicle and walked through the archway of the building. Chapman then shot Lennon twice in the back and twice in the shoulder[171] at close range. Lennon was rushed in a police cruiser to the emergency room of Roosevelt Hospital, where he was pronounced dead on arrival at 11:15 p.m. (EST).[172][173]

Ono issued a statement the next day, saying “There is no funeral for John”, ending it with the words, “John loved and prayed for the human race. Please do the same for him.”[174] His remains were cremated at Ferncliff Cemetery in Hartsdale, New York. Ono scattered his ashes in New York’s Central Park, where the Strawberry Fields memorial was later created.[175] Chapman avoided going to trial when he ignored his lawyer’s advice and pleaded guilty to second-degree murder and was sentenced to 20-years-to-life.[176][nb 6]

In the weeks following the murder, “(Just Like) Starting Over” and Double Fantasy topped the charts in the UK and the US.[178] “Imagine” hit number one in the UK in January 1981 and “Happy Xmas” peaked at number two.[179] “Imagine” was succeeded at the top of the UK chart by “Woman“, the second single from Double Fantasy.[180] Later that year, Roxy Music‘s cover version of “Jealous Guy“, recorded as a tribute to Lennon, was also a UK number-one.[23]

Personal relationships

Cynthia Lennon

Lennon met Cynthia Powell (1939–2015) in 1957, when they were fellow students at the Liverpool College of Art.[181] Although Powell was intimidated by Lennon’s attitude and appearance, she heard that he was obsessed with the French actress Brigitte Bardot, so she dyed her hair blonde. Lennon asked her out, but when she said that she was engaged, he shouted, “I didn’t ask you to fuckin’ marry me, did I?”[182] She often accompanied him to Quarrymen gigs and travelled to Hamburg with McCartney’s girlfriend to visit him.[183]

Lennon was jealous by nature and eventually grew possessive, often terrifying Powell with his anger.[184] In her 2005 memoir John, Powell recalled that, when they were dating, Lennon once struck her after he observed her dancing with Stuart Sutcliffe.[185] She ended their relationship as a result, until three months later, when Lennon apologised and asked to reunite.[186] She took him back and later noted that he was never again physically abusive towards her, although he could still be “verbally cutting and unkind”.[187] Lennon later said that until he met Ono, he had never questioned his chauvinistic attitude towards women. He said that the Beatles song “Getting Better” told his (or his peers’) own story. “I used to be cruel to my woman, and physically – any woman. I was a hitter. I couldn’t express myself and I hit. I fought men and I hit women. That is why I am always on about peace”.[188]

Recalling his July 1962 reaction when he learned that Cynthia was pregnant, Lennon said, “There’s only one thing for it Cyn. We’ll have to get married.”[189] The couple wed on 23 August at the Mount Pleasant Register Office in Liverpool, with Brian Epstein serving as best man. His marriage began just as Beatlemania was taking off across the UK. He performed on the evening of his wedding day and would continue to do so almost daily from then on.[190] Epstein feared that fans would be alienated by the idea of a married Beatle, and he asked the Lennons to keep their marriage secret. Julian was born on 8 April 1963; Lennon was on tour at the time and did not see his infant son until three days later.[191]

Cynthia attributed the start of the marriage breakdown to Lennon’s use of LSD, and she felt that he slowly lost interest in her as a result of his use of the drug.[192] When the group travelled by train to Bangor, Wales in 1967 for the Maharishi Yogi‘s Transcendental Meditation seminar, a policeman did not recognise her and stopped her from boarding. She later recalled how the incident seemed to symbolise the end of their marriage.[193] After spending a holiday in Greece,[194] Cynthia arrived home at Kenwood to find Lennon sitting on the floor with Ono in terrycloth robes[195] and left the house to stay with friends, feeling shocked and humiliated.[196] A few weeks later, Alexis Mardas informed Powell that Lennon was seeking a divorce and custody of Julian.[197] She received a letter stating that Lennon was doing so on the grounds of her adultery with Italian hotelier Roberto Bassanini, an accusation which Powell denied.[198] After negotiations, Lennon capitulated and agreed to let her divorce him on the same grounds.[199] The case was settled out of court in November 1968, with Lennon giving her £100,000, a small annual payment, and custody of Julian.[200]

Brian Epstein

The Beatles were performing at Liverpool’s Cavern Club in November 1961 when they were introduced to Brian Epstein after a midday concert. Epstein was homosexual and closeted, and according to biographer Philip Norman, one of Epstein’s reasons for wanting to manage the group was that he was attracted to Lennon. Almost as soon as Julian was born, Lennon went on holiday to Spain with Epstein, which led to speculation about their relationship. When he was later questioned about it, Lennon said, “Well, it was almost a love affair, but not quite. It was never consummated. But it was a pretty intense relationship. It was my first experience with a homosexual that I was conscious was homosexual. We used to sit in a café in Torremolinos looking at all the boys and I’d say, ‘Do you like that one? Do you like this one?’ I was rather enjoying the experience, thinking like a writer all the time: I am experiencing this.”[201] Soon after their return from Spain, at McCartney’s twenty-first birthday party in June 1963, Lennon physically attacked Cavern Club master of ceremonies Bob Wooler for saying “How was your honeymoon, John?” The MC, known for his wordplay and affectionate but cutting remarks, was making a joke,[202] but ten months had passed since Lennon’s marriage, and the deferred honeymoon was still two months in the future.[203] Lennon was drunk at the time and the matter was simple: “He called me a queer so I battered his bloody ribs in.”[204]

Lennon delighted in mocking Epstein for his homosexuality and for the fact that he was Jewish.[205] When Epstein invited suggestions for the title of his autobiography, Lennon offered Queer Jew; on learning of the eventual title, A Cellarful of Noise, he parodied, “More like A Cellarful of Boys“.[206] He demanded of a visitor to Epstein’s flat, “Have you come to blackmail him? If not, you’re the only bugger in London who hasn’t.”[205] During the recording of “Baby, You’re a Rich Man“, he sang altered choruses of “Baby, you’re a rich fag Jew”.[207][208]

Julian Lennon

During his marriage to Cynthia, Lennon’s first son Julian was born at the same time that his commitments with the Beatles were intensifying at the height of Beatlemania. Lennon was touring with the Beatles when Julian was born on 8 April 1963. Julian’s birth, like his mother Cynthia’s marriage to Lennon, was kept secret because Epstein was convinced that public knowledge of such things would threaten the Beatles’ commercial success. Julian recalled that as a small child in Weybridge some four years later, “I was trundled home from school and came walking up with one of my watercolour paintings. It was just a bunch of stars and this blonde girl I knew at school. And Dad said, ‘What’s this?’ I said, ‘It’s Lucy in the sky with diamonds.'”[209] Lennon used it as the title of a Beatles song, and though it was later reported to have been derived from the initials LSD, Lennon insisted, “It’s not an acid song.”[210] Lennon was distant from Julian, who felt closer to McCartney than to his father. During a car journey to visit Cynthia and Julian during Lennon’s divorce, McCartney composed a song, “Hey Jules”, to comfort him. It would evolve into the Beatles song “Hey Jude“. Lennon later said, “That’s his best song. It started off as a song about my son Julian … he turned it into ‘Hey Jude’. I always thought it was about me and Yoko but he said it wasn’t.”[211]

Lennon’s relationship with Julian was already strained, and after Lennon and Ono moved to New York in 1971, Julian did not see his father again until 1973.[212] With Pang’s encouragement, arrangements were made for Julian and his mother to visit Lennon in Los Angeles, where they went to Disneyland.[213] Julian started to see his father regularly, and Lennon gave him a drumming part on a Walls and Bridges track.[214] He bought Julian a Gibson Les Paul guitar and other instruments, and encouraged his interest in music by demonstrating guitar chord techniques.[214] Julian recalls that he and his father “got on a great deal better” during the time he spent in New York: “We had a lot of fun, laughed a lot and had a great time in general.”[215]

In a Playboy interview with David Sheff shortly before his death, Lennon said, “Sean is a planned child, and therein lies the difference. I don’t love Julian any less as a child. He’s still my son, whether he came from a bottle of whiskey or because they didn’t have pills in those days. He’s here, he belongs to me, and he always will.”[216] He said he was trying to reestablish a connection with the then 17-year-old, and confidently predicted, “Julian and I will have a relationship in the future.”[216] After his death it was revealed that he had left Julian very little in his will.[217]

Yoko Ono

“John and Yoko” redirects here. For other uses, see John and Yoko (disambiguation).

Lennon first met Yoko Ono on 9 November 1966 at the Indica Gallery in London, where Ono was preparing her conceptual art exhibit. They were introduced by gallery owner John Dunbar.[218] Lennon was intrigued by Ono’s “Hammer A Nail”: patrons hammered a nail into a wooden board, creating the art piece. Although the exhibition had not yet begun, Lennon wanted to hammer a nail into the clean board, but Ono stopped him. Dunbar asked her, “Don’t you know who this is? He’s a millionaire! He might buy it.” According to Lennon’s recollection in 1980, Ono had not heard of the Beatles, but she relented on condition that Lennon pay her five shillings, to which Lennon said he replied, “I’ll give you an imaginary five shillings and hammer an imaginary nail in.”[219] Ono subsequently related that Lennon had taken a bite out of the apple on display in her work Apple, much to her fury.[220][nb 7]

Ono began to telephone and visit Lennon at his home. When Cynthia asked him for an explanation, Lennon explained that Ono was only trying to obtain money for her “avant-garde bullshit”.[223] While his wife was on holiday in Greece in May 1968, Lennon invited Ono to visit. They spent the night recording what would become the Two Virgins album, after which, he said, they “made love at dawn”.[224] When Lennon’s wife returned home she found Ono wearing her bathrobe and drinking tea with Lennon who simply said, “Oh, hi.”[225] Ono became pregnant in 1968 and miscarried a male child on 21 November 1968,[175] a few weeks after Lennon’s divorce from Cynthia was granted.[226]

Two years before the Beatles disbanded, Lennon and Ono began public protests against the Vietnam War. They were married in Gibraltar on 20 March 1969,[227] and spent their honeymoon at the Hilton Amsterdam, campaigning with a week-long bed-in. They planned another bed-in in the United States, but were denied entry,[228] so held one instead at the Queen Elizabeth Hotel in Montreal, where they recorded “Give Peace a Chance“.[229] They often combined advocacy with performance art, as in their “Bagism“, first introduced during a Vienna press conference. Lennon detailed this period in the Beatles song “The Ballad of John and Yoko“.[230] Lennon changed his name by deed poll on 22 April 1969, adding “Ono” as a middle name. The brief ceremony took place on the roof of the Apple Corps building, where the Beatles had performed their rooftop concert three months earlier. Although he used the name John Ono Lennon thereafter, some official documents referred to him as John Winston Ono Lennon.[2] The couple settled at Tittenhurst Park at Sunninghill in Berkshire.[231] After Ono was injured in a car accident, Lennon arranged for a king-size bed to be brought to the recording studio as he worked on the Beatles’ album, Abbey Road.[232]

Ono and Lennon moved to New York, to a flat on Bank Street, Greenwich Village. Looking for somewhere with better security, they relocated in 1973 to the more secure Dakota overlooking Central Park at 1 West 72nd Street.[233]

May Pang

ABKCO Industries was formed in 1968 by Allen Klein as an umbrella company to ABKCO Records. Klein hired May Pang as a receptionist in 1969. Through involvement in a project with ABKCO, Lennon and Ono met her the following year. She became their personal assistant. In 1973, after she had been working with the couple for three years, Ono confided that she and Lennon were becoming estranged. She went on to suggest that Pang should begin a physical relationship with Lennon, telling her, “He likes you a lot.” Astounded by Ono’s proposition, Pang nevertheless agreed to become Lennon’s companion. The pair soon left for Los Angeles, beginning an 18-month period he later called his “lost weekend“.[140] In Los Angeles, Pang encouraged Lennon to develop regular contact with Julian, whom he had not seen for two years. He also rekindled friendships with Starr, McCartney, Beatles roadie Mal Evans, and Harry Nilsson.

In June, Lennon and Pang returned to Manhattan in their newly rented penthouse apartment where they prepared a spare room for Julian when he visited them.[234] Lennon, who had been inhibited by Ono in this regard, began to reestablish contact with other relatives and friends. By December, he and Pang were considering a house purchase, and he refused to accept Ono’s telephone calls. In February 1975, he agreed to meet Ono, who claimed to have found a cure for smoking. After the meeting, he failed to return home or call Pang. When Pang telephoned the next day, Ono told her that Lennon was unavailable because he was exhausted after a hypnotherapy session. Two days later, Lennon reappeared at a joint dental appointment; he was stupefied and confused to such an extent that Pang believed he had been brainwashed. Lennon told Pang that his separation from Ono was now over, although Ono would allow him to continue seeing her as his mistress.[235]

Sean Lennon

Ono had previously suffered three miscarriages in her attempt to have a child with Lennon. When Ono and Lennon were reunited, she became pregnant again. She initially said that she wanted to have an abortion but changed her mind and agreed to allow the pregnancy to continue on the condition that Lennon adopt the role of househusband, which he agreed to do.[236]

Following Sean’s birth, Lennon’s subsequent hiatus from the music industry would span five years. He had a photographer take pictures of Sean every day of his first year and created numerous drawings for him, which were posthumously published as Real Love: The Drawings for Sean. Lennon later proudly declared, “He didn’t come out of my belly but, by God, I made his bones, because I’ve attended to every meal, and to how he sleeps, and to the fact that he swims like a fish.”[237]

Former Beatles

Further information: Collaborations between ex-Beatles, Paul McCartney, George Harrison, and Ringo Starr

While Lennon remained consistently friendly with Starr during the years that followed the Beatles’ break-up in 1970, his relationships with McCartney and Harrison varied. He was initially close to Harrison, but the two drifted apart after Lennon moved to the US in 1971. When Harrison was in New York for his December 1974 Dark Horse tour, Lennon agreed to join him on stage but failed to appear after an argument over Lennon’s refusal to sign an agreement that would finally dissolve the Beatles’ legal partnership.[238][nb 8] Harrison later said that when he visited Lennon during his five years away from music, he sensed that Lennon was trying to communicate, but his bond with Ono prevented him.[239][240] Harrison offended Lennon in 1980 when he published I, Me, Mine, an autobiography that Lennon felt made little mention of him.[241] Lennon told Playboy, “I was hurt by it. By glaring omission … my influence on his life is absolutely zilch … he remembers every two-bit sax player or guitarist he met in subsequent years. I’m not in the book.”[242]

Lennon’s most intense feelings were reserved for McCartney. In addition to attacking him with the lyrics of “How Do You Sleep?“, Lennon argued with him through the press for three years after the group split. The two later began to reestablish something of the close friendship they had once known, and in 1974, they even played music together again before eventually growing apart once more. During McCartney’s final visit in April 1976, Lennon said that they watched the episode of Saturday Night Live in which Lorne Michaels made a $3,000 offer to get the Beatles to reunite on the show.[243] According to Lennon, the pair considered going to the studio to make a joke appearance, attempting to claim their share of the money, but they were too tired.[244] Lennon summarised his feelings towards McCartney in an interview three days before his death: “Throughout my career, I’ve selected to work with … only two people: Paul McCartney and Yoko Ono … That ain’t bad picking.”[245]

Along with his estrangement from McCartney, Lennon always felt a musical competitiveness with him and kept an ear on his music. During his career break from 1975 until shortly before his death, according to Fred Seaman, Lennon and Ono’s assistant at the time, Lennon was content to sit back as long as McCartney was producing what Lennon saw as mediocre material.[246] Lennon took notice when McCartney released “Coming Up” in 1980, which was the year Lennon returned to the studio. “It’s driving me crackers!” he jokingly complained, because he could not get the tune out of his head.[246] That same year, Lennon was asked whether the group were dreaded enemies or the best of friends, and he replied that they were neither, and that he had not seen any of them in a long time. But he also said, “I still love those guys. The Beatles are over, but John, Paul, George and Ringo go on.”[247]

Political activism

Further information: Bed-in and Bagism

Lennon and Ono used their honeymoon as a bed-in at the Amsterdam Hilton Hotel; the March 1969 event attracted worldwide media ridicule.[248][249] During a second bed-in three months later at the Queen Elizabeth Hotel in Montreal,[250] Lennon wrote and recorded “Give Peace a Chance”. Released as a single, the song was quickly interpreted as an anti-war anthem and sung by a quarter of a million demonstrators against the Vietnam War in Washington, DC, on 15 November, the second Vietnam Moratorium Day.[95][251] In December, they paid for billboards in 10 cities around the world which declared, in the national language, “War Is Over! If You Want It”.[252]

During the year, Lennon and Ono began to support efforts by the family of James Hanratty to prove his innocence.[253] Hanratty had been hanged in 1962. According to Lennon, those who had condemned Hanratty were “the same people who are running guns to South Africa and killing blacks in the streets … The same bastards are in control, the same people are running everything, it’s the whole bullshit bourgeois scene.”[254] In London, Lennon and Ono staged a “Britain Murdered Hanratty” banner march and a “Silent Protest For James Hanratty”,[255] and produced a 40-minute documentary on the case. At an appeal hearing more than thirty years later, Hanratty’s conviction was upheld after DNA evidence was found to match, validating those who condemned him.[256]

Lennon and Ono showed their solidarity with the Clydeside UCS workers’ work-in of 1971 by sending a bouquet of red roses and a cheque for £5,000.[257] On moving to New York City in August that year, they befriended two of the Chicago Seven, Yippie peace activists Jerry Rubin and Abbie Hoffman.[258] Another political activist, John Sinclair, poet and co-founder of the White Panther Party, was serving ten years in prison for selling two joints of marijuana after previous convictions for possession of the drug.[259] In December 1971 at Ann Arbor, Michigan, 15,000 people attended the “John Sinclair Freedom Rally“, a protest and benefit concert with contributions from Lennon, Stevie Wonder, Bob Seger, Bobby Seale of the Black Panther Party, and others.[260] Lennon and Ono, backed by David Peel and Jerry Rubin, performed an acoustic set of four songs from their forthcoming Some Time in New York City album including “John Sinclair”, whose lyrics called for his release. The day before the rally, the Michigan Senate passed a bill that significantly reduced the penalties for possession of marijuana and four days later Sinclair was released on an appeal bond.[131] The performance was recorded and two of the tracks later appeared on John Lennon Anthology (1998).[261]

Following the Bloody Sunday incident in Northern Ireland in 1972, Lennon said that given the choice between the British army and the IRA he would side with the latter. Lennon and Ono wrote two songs protesting British presence and actions in Ireland for their Some Time in New York City album: “The Luck of the Irish” and “Sunday Bloody Sunday“. In 2000, David Shayler, a former member of Britain’s domestic security service MI5, suggested that Lennon had given money to the IRA, though this was swiftly denied by Ono.[262] Biographer Bill Harry records that following Bloody Sunday, Lennon and Ono financially supported the production of the film The Irish Tapes, a political documentary with an Irish Republican slant.[263] In February 2000 Lennon’s cousin Stanley Parkes stated that the singer had given money to the IRA during the 1970s.[264] After the events of Bloody Sunday Lennon and Ono attended a protest in London while displaying a Red Mole newspaper with the headline “For the IRA, Against British Imperialism”.[265]

Our society is run by insane people for insane objectives. I think we’re being run by maniacs for maniacal ends and I think I’m liable to be put away as insane for expressing that. That’s what’s insane about it.

—John Lennon[266]

According to FBI surveillance reports, and confirmed by Tariq Ali in 2006, Lennon was sympathetic to the International Marxist Group, a Trotskyist group formed in Britain in 1968.[267] However, the FBI considered Lennon to have limited effectiveness as a revolutionary, as he was “constantly under the influence of narcotics”.[268]

In 1972, Lennon contributed a drawing and limerick titled “Why Make It Sad to Be Gay?” to Len Richmond and Gary Noguera’s The Gay Liberation Book.[269][270] Lennon’s last act of political activism was a statement in support of the striking minority sanitation workers in San Francisco on 5 December 1980. He and Ono planned to join the workers’ protest on 14 December.[271]

Deportation attempt

Following the impact of “Give Peace a Chance” and “Happy Xmas (War Is Over)” on the anti-war movement, the Nixon administration heard rumours of Lennon’s involvement in a concert to be held in San Diego at the same time as the Republican National Convention[272] and tried to have him deported. Nixon believed that Lennon’s anti-war activities could cost him his reelection;[273] Republican Senator Strom Thurmond suggested in a February 1972 memo that “deportation would be a strategic counter-measure” against Lennon.[274] The next month the United States Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) began deportation proceedings, arguing that his 1968 misdemeanour conviction for cannabis possession in London had made him ineligible for admission to the United States. Lennon spent the next 3+1⁄2 years in and out of deportation hearings until 8 October 1975, when a court of appeals barred the deportation attempt, stating “the courts will not condone selective deportation based upon secret political grounds”.[275][133] While the legal battle continued, Lennon attended rallies and made television appearances. He and Ono co-hosted The Mike Douglas Show for a week in February 1972, introducing guests such as Jerry Rubin and Bobby Seale to mid-America.[276] In 1972, Bob Dylan wrote a letter to the INS defending Lennon, stating:

John and Yoko add a great voice and drive to the country’s so-called art institution. They inspire and transcend and stimulate and by doing so, only help others to see pure light and in doing that, put an end to this dull taste of petty commercialism which is being passed off as Artist Art by the overpowering mass media. Hurray for John and Yoko. Let them stay and live here and breathe. The country’s got plenty of room and space. Let John and Yoko stay![277][278]

On 23 March 1973, Lennon was ordered to leave the US within 60 days.[279] Ono, meanwhile, was granted permanent residence. In response, Lennon and Ono held a press conference on 1 April 1973 at the New York City Bar Association, where they announced the formation of the state of Nutopia; a place with “no land, no boundaries, no passports, only people”.[280] Waving the white flag of Nutopia (two handkerchiefs), they asked for political asylum in the US. The press conference was filmed, and appeared in a 2006 documentary, The U.S. vs. John Lennon.[281][nb 9] Soon after the press conference, Nixon’s involvement in a political scandal came to light, and in June the Watergate hearings began in Washington, D.C.. They led to the president’s resignation 14 months later.[283] In December 1974, when he and members of his tour entourage visited the White House, Harrison asked Gerald Ford, Nixon’s successor, to intercede in the matter.[284] Ford’s administration showed little interest in continuing the battle against Lennon, and the deportation order was overturned in 1975. The following year, Lennon received his green card certifying his permanent residency, and when Jimmy Carter was inaugurated as president in January 1977, Lennon and Ono attended the Inaugural Ball.[283]

FBI surveillance and declassified documents

Further information: Jon Wiener § Wiener and the Lennon FBI files

After Lennon’s death, historian Jon Wiener filed a Freedom of Information Act request for FBI files that documented the Bureau’s role in the deportation attempt.[285] The FBI admitted it had 281 pages of files on Lennon, but refused to release most of them on the grounds that they contained national security information. In 1983, Wiener sued the FBI with the help of the American Civil Liberties Union of Southern California. It took 14 years of litigation to force the FBI to release the withheld pages.[286] The ACLU, representing Wiener, won a favourable decision in their suit against the FBI in the Ninth Circuit in 1991.[287][288] The Justice Department appealed the decision to the Supreme Court in April 1992, but the court declined to review the case.[289] In 1997, respecting President Bill Clinton‘s newly instigated rule that documents should be withheld only if releasing them would involve “foreseeable harm”, the Justice Department settled most of the outstanding issues outside court by releasing all but 10 of the contested documents.[289]

Wiener published the results of his 14-year campaign in January 2000. Gimme Some Truth: The John Lennon FBI Files contained facsimiles of the documents, including “lengthy reports by confidential informants detailing the daily lives of anti-war activists, memos to the White House, transcripts of TV shows on which Lennon appeared, and a proposal that Lennon be arrested by local police on drug charges”.[290] The story is told in the documentary The US vs. John Lennon. The final 10 documents in Lennon’s FBI file, which reported on his ties with London anti-war activists in 1971 and had been withheld as containing “national security information provided by a foreign government under an explicit promise of confidentiality”, were released in December 2006. They contained no indication that the British government had regarded Lennon as a serious threat; one example of the released material was a report that two prominent British leftists had hoped Lennon would finance a left-wing bookshop and reading room.[291]

Writing

Beatles biographer Bill Harry wrote that Lennon began drawing and writing creatively at an early age with the encouragement of his uncle. He collected his stories, poetry, cartoons and caricatures in a Quarry Bank High School exercise book that he called the Daily Howl. The drawings were often of crippled people, and the writings satirical, and throughout the book was an abundance of wordplay. According to classmate Bill Turner, Lennon created the Daily Howl to amuse his best friend and later Quarrymen bandmate Pete Shotton, to whom he would show his work before he let anyone else see it. Turner said that Lennon “had an obsession for Wigan Pier. It kept cropping up”, and in Lennon’s story A Carrot in a Potato Mine, “the mine was at the end of Wigan Pier.” Turner described how one of Lennon’s cartoons depicted a bus stop sign annotated with the question, “Why?” Above was a flying pancake, and below, “a blind man wearing glasses leading along a blind dog – also wearing glasses”.[292]

Lennon’s love of wordplay and nonsense with a twist found a wider audience when he was 24. Harry writes that In His Own Write (1964) was published after “Some journalist who was hanging around the Beatles came to me and I ended up showing him the stuff. They said, ‘Write a book’ and that’s how the first one came about”. Like the Daily Howl it contained a mix of formats including short stories, poetry, plays and drawings. One story, “Good Dog Nigel”, tells the tale of “a happy dog, urinating on a lamp post, barking, wagging his tail – until he suddenly hears a message that he will be killed at three o’clock”. The Times Literary Supplement considered the poems and stories “remarkable … also very funny … the nonsense runs on, words and images prompting one another in a chain of pure fantasy”. Book Week reported, “This is nonsense writing, but one has only to review the literature of nonsense to see how well Lennon has brought it off. While some of his homonyms are gratuitous word play, many others have not only double meaning but a double edge.” Lennon was not only surprised by the positive reception, but that the book was reviewed at all, and suggested that readers “took the book more seriously than I did myself. It just began as a laugh for me”.[293]

In combination with A Spaniard in the Works (1965), In His Own Write formed the basis of the stage play The Lennon Play: In His Own Write,[294] co-adapted by Victor Spinetti and Adrienne Kennedy.[295] After negotiations between Lennon, Spinetti and the artistic director of the National Theatre, Sir Laurence Olivier, the play opened at The Old Vic in 1968. Lennon and Ono attended the opening night performance, their second public appearance together.[295] In 1969, Lennon wrote “Four in Hand”, a skit based on his teenage experiences of group masturbation, for Kenneth Tynan‘s play Oh! Calcutta![296] After Lennon’s death, further works were published, including Skywriting by Word of Mouth (1986), Ai: Japan Through John Lennon’s Eyes: A Personal Sketchbook (1992), with Lennon’s illustrations of the definitions of Japanese words, and Real Love: The Drawings for Sean (1999). The Beatles Anthology (2000) also presented examples of his writings and drawings.

Art

In 1967, Lennon, who had attended art school, funded and anonymously participated in Ono’s art exhibition Half-A-Room that was held at Lisson Gallery. Following his collaborating with Ono in the form of The Plastic Ono Band that began in 1968, Lennon became involved with the Fluxus art movement. In the summer of 1968, Lennon began showing his painting and conceptual art at his You Are Here art exhibition held at Robert Fraser Gallery in London.[297] The show, that was dedicated to Ono, included a six foot in diameter round white monochrome painting called You Are Here (1968). Besides the white monochrome paint, its surface contained only the tiny hand written inscription “you are here”. This painting, and the show in general, was conceived as a response to Ono’s conceptual art piece This is Not Here (1966) that was part of her Fluxus installation of wall text pieces called Blue Room Event (1966). Blue Room Event consisted of sentences that Ono wrote directly on her white New York apartment walls and ceiling. Lennon’s You Are Here show also included sixty charity collection boxes, a pair of Lennon’s shoes with a sign that read “I take my shoes off to you”, a ready made black bike (an apparent homage to Marcel Duchamp and his 1917 Bicycle Wheel), an overturned white hat labeled For The Artist, and a large glass jar full of free-to-take you are here white pin badges.[298] A hidden camera secretly filmed the public reaction to the show.[299] For the 1 July opening, Lennon, dressed all in white (as was Ono), released 365 white balloons into the city sky. Each ballon had attached to it a small paper card to be mailed back to Lennon at the Robert Fraser Gallery at 69 Duke Street, with the finder’s comments.[300]

After moving to New York City, from 18 April to 12 June 1970, Lennon and Ono presented a series of Fluxus conceptual art events and concerts at Joe Jones‘s Tone Deaf Music Store called GRAPEFRUIT FLUXBANQUET. Performances included Come Impersonating John Lennon & Yoko Ono, Grapefruit Banquet and Portrait of John Lennon as a Young Cloud by Yoko + Everybody.[301] That same year, Lennon also made The Complete Yoko Ono Word Poem Game (1970): a conceptual art poem collage that utilized the cut-up (or découpé) aleatory technique typical of the work of John Cage and many Fluxus artists. The cut-up technique can be traced to at least the Dadaists of the 1920s, but was popularized in the early 1960s by writer William S. Burroughs. For The Complete Yoko Ono Word Poem Game, Lennon took the portrait photo of himself that was included in the packaging of the 1968 The Beatles LP (aka The White Album) and cut it into 134 small rectangles. A single word was written on the back of each fragment, to be read in any order. The portrait image was meant to be reassembled in any order. The Complete Yoko Ono Word Poem Game was presented by Lennon to Ono on 28 July in an inscribed envelope for her to randomly assemble and reassemble at will.[302]

Lennon made whimsical drawings and fine art prints on occasion until the end of his life.[303] For example, Lennon exhibited at Eugene Schuster’s London Arts Gallery his Bag One lithographs in an exhibition that included several depicting erotic imagery. The show opened on 15 January 1970 and 24 hours later it was raided by police officers who confiscated 8 of the 14 lithos on the grounds of indecency. The lithographs had been drawn by Lennon in 1969 chronicling his wedding and honeymoon with Yoko Ono and one of their bed-ins staged in the interests of world peace.[304]

In 1969, Lennon appeared in the Yoko Ono Fluxus art film Self-Portrait, which consisted of a single forty-minute shot of Lennon’s penis.[305] The film was premiered at the Institute of Contemporary Arts.[306][307] In 1971, Lennon made an experimental art film called Erection that was edited on 16 mm film[308] by George Maciunas, founder of the Fluxus art movement and avant-garde contemporary of Ono.[309] The film uses the songs “Airmale” and “You” from Ono’s 1971 album Fly, as its soundtrack.[310]

Musicianship

Instruments played

Further information: John Lennon’s musical instruments and List of the Beatles’ instruments

Lennon played a mouth organ during a bus journey to visit his cousin in Scotland; the music caught the driver’s ear. Impressed, the driver told Lennon of a harmonica he could have if he came to Edinburgh the following day, where one had been stored in the bus depot since a passenger had left it on a bus.[311] The professional instrument quickly replaced Lennon’s toy. He would continue to play the harmonica, often using the instrument during the Beatles’ Hamburg years, and it became a signature sound in the group’s early recordings. His mother taught him how to play the banjo, later buying him an acoustic guitar. At 16, he played rhythm guitar with the Quarrymen.[312]

As his career progressed, he played a variety of electric guitars, predominantly the Rickenbacker 325, Epiphone Casino and Gibson J-160E, and, from the start of his solo career, the Gibson Les Paul Junior.[313][314] Double Fantasy producer Jack Douglas claimed that since his Beatle days Lennon habitually tuned his D-string slightly flat, so his Aunt Mimi could tell which guitar was his on recordings.[315] Occasionally he played a six-string bass guitar, the Fender Bass VI, providing bass on some Beatles numbers (“Back in the U.S.S.R.“, “The Long and Winding Road“, “Helter Skelter”) that occupied McCartney with another instrument.[316] His other instrument of choice was the piano, on which he composed many songs, including “Imagine”, described as his best-known solo work.[317] His jamming on a piano with McCartney in 1963 led to the creation of the Beatles’ first US number one, “I Want to Hold Your Hand“.[318] In 1964, he became one of the first British musicians to acquire a Mellotron keyboard, though it was not heard on a Beatles recording until “Strawberry Fields Forever” in 1967.[319]

In 2024, a guitar of John Lennon’s that was thought to have been lost, was found in the attic of a 90-year-old man who was the manager of the pop duo Peter and Gordon in the 60s. The duo had friendly relations with members of the Beatles, and Gordon Waller, one of the duo’s members, had received the guitar from Lennon in 1965 and then gave it to his manager. The 12-string acoustic musical instrument had been used to record songs on the Beatles’ 1965 studio album “Help!”. It was auctioned at Julien’s Auctions for $2.9 million (2.68 million euros), breaking a record. In 2015, Lennon’s previous acoustic guitar, a Gibson J160E, sold for a then-record $2.4 million (€2.2 million).[320]

Vocal style

The British critic Nik Cohn observed of Lennon, “He owned one of the best pop voices ever, rasped and smashed and brooding, always fierce.” Cohn wrote that Lennon, performing “Twist and Shout“, would “rant his way into total incoherence, half rupture himself.”[321] When the Beatles recorded the song, the final track during the mammoth one-day session that produced the band’s 1963 debut album, Please Please Me, Lennon’s voice, already compromised by a cold, came close to giving out. Lennon said, “I couldn’t sing the damn thing, I was just screaming.”[322] In the words of biographer Barry Miles, “Lennon simply shredded his vocal cords in the interests of rock ‘n’ roll.”[323] The Beatles’ producer, George Martin, tells how Lennon “had an inborn dislike of his own voice which I could never understand. He was always saying to me: ‘DO something with my voice! … put something on it … Make it different.'”[324] Martin obliged, often using double-tracking and other techniques.[325][326]

As his Beatles era segued into his solo career, his singing voice found a widening range of expression. Biographer Chris Gregory writes of Lennon “tentatively beginning to expose his insecurities in a number of acoustic-led ‘confessional’ ballads, so beginning the process of ‘public therapy’ that will eventually culminate in the primal screams of ‘Cold Turkey‘ and the cathartic John Lennon/Plastic Ono Band.”[327] Music critic Robert Christgau called this Lennon’s “greatest vocal performance … from scream to whine, is modulated electronically … echoed, filtered, and double tracked.”[328] David Stuart Ryan described Lennon’s vocal delivery as ranging from “extreme vulnerability, sensitivity and even naivety” to a hard “rasping” style.[329] Wiener too described contrasts, saying the singer’s voice can be “at first subdued; soon it almost cracks with despair”.[330] Music historian Ben Urish recalled hearing the Beatles’ Ed Sullivan Show performance of “This Boy” played on the radio a few days after Lennon’s murder: “As Lennon’s vocals reached their peak … it hurt too much to hear him scream with such anguish and emotion. But it was my emotions I heard in his voice. Just like I always had.”[331]

Legacy

Music historians Schinder and Schwartz wrote of the transformation in popular music styles that took place between the 1950s and the 1960s. They said that the Beatles’ influence cannot be overstated: having “revolutionised the sound, style, and attitude of popular music and opened rock and roll’s doors to a tidal wave of British rock acts”, the group then “spent the rest of the 1960s expanding rock’s stylistic frontiers”.[332] On National Poetry Day in 1999, the BBC conducted a poll to identify the UK’s favourite song lyric and announced “Imagine” as the winner.[119]

Two home recording demos by Lennon, “Free as a Bird” and “Real Love“, were finished by the three surviving members of the Beatles when they reunited in 1994 and 1995.[333] Both songs were released as Beatles singles in conjunction with The Beatles Anthology compilations. A third song, “Now and Then“, was also worked on but not released until 2023 whereupon it was dubbed “the last Beatles song”, topping the UK charts.[333][334]

In 1997, Yoko Ono and the BMI Foundation established an annual music competition programme for songwriters of contemporary musical genres to honour John Lennon’s memory and his large creative legacy.[335] Over $400,000 have been given through BMI Foundation’s John Lennon Scholarships to talented young musicians in the United States.[335]

In a 2006 Guardian article, Jon Wiener wrote: “For young people in 1972, it was thrilling to see Lennon’s courage in standing up to [US President] Nixon. That willingness to take risks with his career, and his life, is one reason why people still admire him today.”[336] For music historians Urish and Bielen, Lennon’s most significant effort was “the self-portraits … in his songs [which] spoke to, for, and about, the human condition.”[337] Writing for El País in 2024, Amaia Odriozola described Lennon’s Windsor glasses as being “known all over the world” and credited him with pioneering glasses as a “style statement” for musicians.[338]