KENNEDY-NIXON DEBATE/ CARTER-REAGEN DEBATE

Explore the Constitution

Dive Deeper

- Constitution 101 Course

- The Drafting Table

- Supreme Court Cases Library

- Founders’ Library

- Constitutional Rights: Origins & Travels

Constitution 101 Course

Start your constitutional learning journey

- News & Debate Overview

- Constitution Daily Blog

- Podcasts

- America’s Town Hall Programs

- Special Projects

- Media Library

America’s Town Hall

Watch videos of recent programs

- Education Overview

- Constitution 101 Curriculum

- Classroom Resources by Topic

- Classroom Resources Library

- Live Online Events

- Professional Learning Opportunities

- Constitution Day Resources

- Election Teaching Resources

Constitution 101 With Khan Academy

Explore our new course that empowers students to learn the Constitution at their own pace.

- Explore the Museum

- Plan Your Visit

- Exhibits & Programs

- Field Trips & Group Visits

- Host Your Event

- Buy Tickets

Address

525 Arch Street

Philadelphia, PA 19106

215.409.6600

Get Directions

Hours

Wednesday – Sunday, 10 a.m. – 5 p.m.

New exhibit

The First Amendment

Blog Post

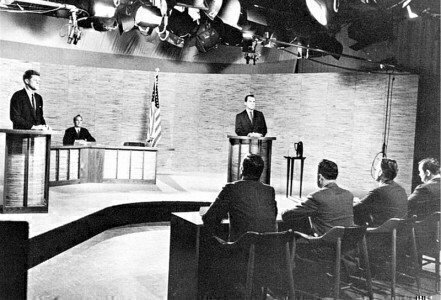

How the Kennedy-Nixon debate changed the world of politics

September 26, 2017 | by NCC Staff More in Constitution Daily Blog

September 26, 1960 is the day that changed part of the modern political landscape, when a Vice President and a Senator took part in the first nationally televised presidential debate.

The Vice President was Richard M. Nixon and the U.S. Senator was John F. Kennedy. Their first televised debate shifted how presidential campaigns were conducted, as the power of television took elections into American’s living rooms.

The debate was watched live by 70 million Americans and it made politics an electronic spectator sport. It also gave many potential voters their first chance to see actual presidential candidates in a live environment, as potential leaders.

The importance of the event can’t be underestimated. Before 1960, there were candidates who debated (Abraham Lincoln and Stephen Douglas were 19th century examples) and there were candidates who appeared on television. And there were candidates who went out on the trail and “stumped” for votes, appearing in public at pre-arranged events or at whistle-stop tours on trains.

But most voters never had a chance to see candidates in a close, personal way, giving them the opportunity to form an opinion about the next president based on their looks, their voice and their opinions.

Going into the debate, Nixon was the favorite to win the election. He had been President Dwight Eisenhower’s vice president for eight years. Nixon had shown his mastery of television in his 1952 “Checkers” speech, where he used a televised address to debunk slush-fund allegations, and secure his vice presidential slot by talking about his pet dog, Checkers. Nixon had also bested Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev in the famous Kitchen Debate.

Kennedy was the photogenic and energetic young senator from Massachusetts who ran a calculated primary campaign to best his chief rival, Senator Lyndon Johnson. But Kennedy had debate experience in the primaries and said, “Nixon may have debated Khrushchev, but I had to debate Hubert Humphrey.”

The debate took place in Chicago and CBS assigned a 38-year-old producer named Don Hewitt to manage the event. Hewitt went on to create “60 Minutes” for CBS. The highly promoted event would pre-empt “The Andy Griffith Show” and run for an hour. Hewitt had invited both candidates to a pre-production meeting, but only Kennedy took up the offer.

When Nixon arrived for the debate, he looked ill, having been recently hospitalized because of a knee injury. The vice president then re-injured his knee as he entered the TV station, and refused to call off the debate.

Nixon also refused to wear stage makeup, when Hewitt offered it. Kennedy had turned down the makeup offer first: He had spent weeks tanning on the campaign trail, but he had his own team do his makeup just before the cameras went live. The result was that Kennedy looked and sounded good on television, while Nixon looked pale and tired, with a five o’clock shadow beard.

The next day, polls showed Kennedy had become the slight favorite in the general election, and he defeated Nixon by one of the narrowest margins in history that November. Before the debate, Nixon led by six percentage points in the national polls.

There were three other debates between Nixon and Kennedy that fall, and a healthier Nixon was judged to have won two of them, with the final debate a draw. However, the last three debates were watched by 20 million fewer people than the September 26th event.

In the aftermath of the first debate, Nixon’s running mate, Henry Cabot Lodge, had a few choice words for the GOP presidential candidate. “That son-of-a-bitch just lost us the election,” Lodge reportedly said. Johnson, who was Kennedy’s running mate, thought his running mate had lost the debate. Lodge saw the debate on TV, while Johnson listened to the debate on the radio.

The event’s aura of being a game changer was so strong that in the following three campaigns, the sitting president refused to debate any challenger. It was Gerald Ford in 1976 who established the current tradition of televised presidential debates in every general election.

Ford became the first sitting president to take part in a televised debate. During his second debate with Jimmy Carter in San Francisco, President Ford said, “There is no Soviet domination of Eastern Europe.” The gaffe was seen as a key factor in Carter’s win over Ford.

Presidential debates became a fixture in 1980, after the GOP challenger, Ronald Reagan, used a strong debate performance just a week before the election to win by a comfortable margin over Carter.

Explore Further

Podcast

Brnovich v. DNC, the Supreme Court, and Voting Rights

Experts discuss the recent major Supreme Court ruling about Arizona’s voting laws.

Jul 8

Town Hall Video

The Past Four Years: What Have We Learned?

Journalists and scholars from across the spectrum discuss the impact and legacy of the past four years on American law and…

Nov 11

Blog Post

On this day, the Republican Party names its first candidates

On July 6, 1854, disgruntled voters in a new political party named its first candidates to contest the Democrats over the issue of…

Jul 6

Podcast

Constitutional Issues in Voting Rights Today

Two election law experts explore various voting laws proposed in the wake of the 2020 election.

May 20

More from the National Constitution Center

Constitution 101

Explore our new 15-unit core curriculum with educational videos, primary texts, and more.

Media Library

Search and browse videos, podcasts, and blog posts on constitutional topics.

Founders’ Library

Discover primary texts and historical documents that span American history and have shaped the American constitutional tradition.

525 Arch Street

Philadelphia, PA 19106

Sign up for our email newsletter

© 2024 National Constitution Center. All Rights Reserved.

Constitution Daily Blog

Text Area for Copy