MALES AGRESSION TOWARD FEMALES

An official website of the United States governmentHere’s how you know

Search in PMC

As a library, NLM provides access to scientific literature. Inclusion in an NLM database does not imply endorsement of, or agreement with, the contents by NLM or the National Institutes of Health.

Learn more: PMC Disclaimer | PMC Copyright Notice J Marriage Fam

J Marriage Fam

. Author manuscript; available in PMC: 2009 Jan 2.

Published in final edited form as: J Marriage Fam. 2008 Dec;70(5):1169–1187. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2008.00558.x

Men’s Aggression Toward Women

A 10-Year Panel Study

Hyoun K Kim 1, Heidemarie K Laurent 1,*, Deborah M Capaldi 1, Alan Feingold 1

- Author information

- Copyright and License information

PMCID: PMC2613333 NIHMSID: NIHMS73245 PMID: 19122790

The publisher’s version of this article is available at J Marriage Fam

Abstract

The present study examined the longitudinal course of men’s physical and psychological aggression toward a partner across 10 years, using a community sample of young couples (N = 194) from at-risk backgrounds. Findings indicated that men’s aggression decreased over time and that women’s antisocial behavior and depressive symptoms predicted changes in men’s aggression. This suggests the importance of studying social processes within the dyad to have a better understanding of men’s aggression toward a partner.

Keywords: Aggression, depressive symptoms, antisocial behavior, longitudinal

Aggression toward a partner in both physically and verbally or emotionally abusive forms has very negative outcomes for adults, including injury (Archer, 2000) and relationship breakdown (Lawrence & Bradbury, 2001). Understanding intraindividual changes in partner aggression would be highly informative for prevention and treatment programs and thus is a key research priority. Several studies on nationally representative and community samples have indicated that the prevalence rates of aggression toward a partner tend to be highest at young ages and to decrease with age (Archer; Gelles, & Straus, 1988). On the basis of cross-sectional data, O’Leary (1999) estimated that the prevalence of physical aggression by men would show a sharp rise from ages 15 – 25 years, a peak prevalence at around age 25 years, and a sharp decline to about age 35 years. Studies of partner aggression, however, have mainly been confined to either cross-sectional or short-term longitudinal data and are primarily descriptive; thus, little is known about the important issues of desistance and persistence in men’s aggression toward a partner, especially across the ages of the early 20s through early 30s, and how these intraindividual changes unfold over time.

Evidence from other areas of couples’ research, such as clinical and social psychological research on interpersonal processes in couples relationships (see Robins, Caspi, & Moffitt, 2000, for further discussion), have all indicated that characteristics of both men and women play a crucial role in the adjustment of male-female romantic dyads. Such dyadic perspectives have remained relatively unattended in the partner aggression field, however, despite findings from recent developmental research in the past 10 years on the dyadic nature of aggression in couples (e.g., Andrews, Foster, Capaldi, & Hops, 2000; Capaldi & Clark, 1998; Magdol, Moffitt, Capsi, & Silva, 1998; Woodward, Fergusson, & Horwood, 2002). Men’s aggression has been routinely viewed as a result of men’s own characteristics, whereas possible partner effects or relational aspects within the dyad have been less considered (Capaldi & Kim, 2007). Partly because of failure to recognize partner effects and relational aspects, partner aggression has been viewed as a static phenomenon rather than an evolving process. Consequently, both the longer-term course of partner aggression and the processes underlying intraindividual change over time are not well understood. The major goals of the present study were to increase understanding of the long-term course of partner aggression for men, including both physical and psychological aggression, and of the individual and relationship factors that predicted increases or decreases in aggression over time. To address these goals, trajectories of men’s physical and psychological aggression were each examined over 10 years in early adulthood (early 20s through early 30s). Predictors examined include both men’s and their partners’ psychopathology (antisocial behavior and depressive symptoms), as well as relationship satisfaction and characteristics of the relationship.

Persistence and Desistance of Physical Aggression by Men

Studies on samples of young adults, such as cohabiting or newlywed couples (Aldarondo, 1996; Mihalic, Elliott, & Menard, 1994) and the National Family Violence Survey (Feld & Straus, 1990), have been consistent in finding desistance rates of around 50% over a 1-year period for men who had shown any violence (suggesting that persistence rates were also around 50%). In a community sample of newlywed couples in which, 1 month prior to marriage, men were identified as physically aggressive toward a partner, Lorber and O’Leary (2004) found that about 41% of the men remained consistently physically aggressive toward a partner across the first 30 months of marriage, and about 23% of the men reported desistence after marriage. Quigley and Leonard (1996) reported similar desistance rates of 24% over the first 3 years of marriage. Overall, therefore, the trend to desistance from partner aggression over time for men seems substantial, but desistance is not universal.

There have been only a few studies that have examined changes in severity or levels of partner aggression over time. Jacobson, Gottman, Gortner, Berns, and Shortt (1996) found that 46% of severely violent men remained so 2 years later, but of those who showed decreases in frequency, only 7% completely desisted in physical aggression toward a partner. Furthermore, emotional abuse did not decrease over 2 years for the sample. Fritz and O’Leary (2004) found that, on average, men’s physical aggression tended to decrease across time, regardless of severity, whereas Lawrence and Bradbury (2007) found no evidence of systematic increase or decrease in physical aggression. They found also that the stability of physical aggression tended to vary as a function of initial level of severity; those who were severely aggressive at the beginning of marriage showed a significant decrease over time, whereas mean levels of aggression remained relatively stable for those who were nonaggressive or moderately aggressive early in marriage.

Although findings from these studies provide some information about prevalence rates of partner aggression and rates of persistence and desistance, mechanisms associated with intraindividual change over time have been little considered. In addition, previous studies frequently have involved only married couples who remain intact over time (Rhule-Louie & McMahon, 2007). Given that individuals from more deprived and risky backgrounds are especially less likely to marry (White & Rogers, 2000) and their relationships tend to be less stable (Rhule-Louie & McMahon), studies on married couples only provide limited information. Further clarification of intraindividual changes among young couples who are in early adulthood and in less committed relationships and mechanisms for such changes in men’s aggression toward a partner will allow us to identify those who are at higher risk for partner aggression and, consequently, to develop more targeted and effective programs.

Psychological Aggression

Psychological aggression, sometimes termed “emotional abuse,” is closely associated with physical aggression and has been reported by many physically abused women to have a more severe impact than the physical abuse (Follingstad, Rutledge, Berg, Hause, & Polek, 1990). O’Leary, Malone, and Tyree (1994) argued that psychological aggression may be very detrimental to one’s well-being and tend to predict later physical aggression. Similarly, Schumacher and Leonard (2005) found that both husbands’ and wives’ verbal aggression longitudinally predicted their own physical aggression. In particular, young couples who do not have positive interaction and problem-solving skills are known to be at greater risk for both psychological and physical aggression (Capaldi & Clark, 1998). Studies on longitudinal trajectories of psychological aggression, however, are even more scarce (Fritz & O’Leary, 2004) and have shown inconsistent findings in terms of longitudinal patterns of such aggression. Aldarondo (1996) found that psychological aggression tended to decrease over a 2-year period among men in a community sample, and the men showed decreases in physical aggression during the same period of time. On the other hand, Fritz and O’Leary found no significant pattern of change in psychological aggression across the first 120 months of marriage. Further knowledge of long-term trajectories and differential mechanisms involved in psychological aggression, as well as physical aggression, is much needed.

A Dynamic Developmental Systems Perspective and Both Partners’ Risk Characteristics

Unlike many studies on men’s aggression toward a partner from traditional feminist theories, the Dynamic Developmental Systems (DDS) approach focuses on the intimate dyad as key to understanding men’s aggression toward a partner, rather than focusing only on men’s characteristics. The DDS model was developed on the basis of recent developmental research on young men’s and women’s aggression perpetration that indicated the importance of developmental risk of both partners (such as antisocial behavior) and the dyadic nature of partner aggression (e.g., Andrews et al., 2000; Capaldi, Shortt, & Crosby, 2003; Kim & Capaldi, 2004; Woodward et al., 2002). Other researchers in the area have also developed models with a similar dyadic focus (Riggs & O’Leary, 1989), but we find the DDS model is particularly useful for conceptualizing the developmental mechanisms of partner aggression, the course of such aggression over time, and bidirectional influences on the behavior and course. Partner aggression is hypothesized to be influenced by characteristics of both members of the couple as they enter and then move through the relationship, including personality, psychopathology, ongoing social influences, and individual developmental stage. In addition, the DDS model emphasizes the nature of the relationship itself, primarily the interaction patterns and proximal contextual factors within the dyad as they are initially established and as they change over time (Capaldi, Shortt, & Kim, 2005). A key feature of the DDS approach is that it includes influences of biological systems. Although not directly tested in this study, neurological maturity, with completion of major brain development (Casey, Tottenham, Liston, & Durston, 2005) and thus the maturity of inhibitory control systems (Welsh, Pennington, & Groisser, 1991), is posited to be related to decreases in aggressive and violent behavior with age (Capaldi, Kim, & Owen, 2008).

Adolescents and young adults with a history of conduct problems or antisocial behavior tend to have higher levels of impulsive and aggressive behaviors and more conflictual interpersonal relationships, and evidence of risk for perpetration of partner aggression from antisocial behavior in men and women has been relatively well documented as aforementioned (Keenan-Miller, Hammen, & Brennan, 2007). Perhaps less widely recognized is the fact that depressive symptoms are also associated with aggression toward a partner in young women (e.g.,Kim & Capaldi, 2004; Marshall & Holtzworth-Munroe, 2002) and in men (Dutton, 1994; Holtzworth-Munroe & Stuart, 1994; Pan, Neidig, & O’Leary, 1994). According to a recent meta-analysis (Stith, Smith, Penn, Ward, & Tritt, 2003), concurrent depressive symptomatology is a risk factor for both men’s violence perpetration and women victimization. Overall, men who are aggressive toward a partner have higher levels of depressive symptoms than do nonagressive men (Pan et al.; Vivian & Malone, 1997). Pan et al. found depressive symptoms to be useful in identifying violent husbands; a 20% increase in depressive symptoms was associated with a 30% increase in the risk for perpetrating mild levels of aggression (e.g., grabbing) and a 74% increase in the use of severe violence (e.g., beating up). A few longitudinal studies, however, have indicated that women’s, but not men’s, depressive symptoms predicted men’s aggression toward a partner (Cleveland, Herrera, & Stuewig, 2003; Kim & Capaldi). Although the mechanisms are not yet clear, the negative affect and irritability that are symptomatic of depression may relate to more aggressive behavior by both women and by their partners.

In addition, romantic partners are likely to show similarity in their developmental risk for partner aggression, and such similarity may result in particularly high risk for violence. Recent developmental studies have consistently indicated significant associations across partners, or assortative partnering, for problem behaviors that are associated with risk for mutually violent relationships such as antisocial behavior and substance use (Kim & Capaldi, 2004; Moffitt, Caspi, Rutter, & Silva, 2001; Quinton, Pickles, Maughan, & Rutter, 1993). In a prior study with the present sample (using two time points in the early 20s), Kim and Capaldi found that antisocial behavior and depressive symptoms show significant associations across partners and that women’s depressive symptoms were found to be predictive of men’s psychological aggression over time, controlling for other factors. These studies suggest that concordance for individual risk characteristics across partners may result in mutually reinforcing social processes within the dyad. Although social influence processes by peers have drawn a great deal of attention, partner influence in close relationships has been less of a focus in the literature, especially in the partner violence literature. Romantic relationships are often considered as a positive force for at-risk men, serving as a turning point that facilitates men’s desistance from delinquency (e.g., Sampson & Laub, 2003). Given the evidence that individuals tend to actively select compatible partners who are supportive of their behavior, men’s problem behaviors are likely to be reinforced and maintained in some cases (Quinton et al.). Similar to the deviant peer training process (Dishion, Eddy, Haas, Li, & Spracklen, 1997), partners’ problem behavior and risk characteristics may operate to maintain or exacerbate problem behaviors in individuals (Capaldi et al., 2008; Moffitt et al., 2001; Rhule-Louie & McMahon, 2007). This suggests that considering both partners and their behaviors as a dynamic system is crucial in partner aggression prevention and intervention programs for at-risk populations.

The Present Study

The primary purpose of the present study was to examine the extent to which men persist or desist in aggression toward a partner (physical and psychological) over an extended period from their early 20s through early 30s. Following the findings from previous studies and the DDS model, we expected that men’s aggression would decrease, in general, over time, but that variations among men in patterns over time would be significantly influenced by their own and their partners’ antisocial behavior and depressive symptoms. Specifically, we hypothesized that men with higher levels of antisocial behavior or depressive symptoms would show less desistance of aggression over time and, thus, be less likely to follow the normative trend toward desistance. Also hypothesized was that similar risk factors for the women would contribute to the man’s aggression trajectory above and beyond the contribution of his own risk factors. Finally, when a man with higher levels of problem behaviors pairs off with a partner who also has higher levels of problem behaviors, the combination of the men’s and women’s risk and resulting negative interchanges could exacerbate the men’s aggression over and above additive effects. Conversely, a partner very low in risk behavior could dampen down men’s risk for aggression. Moderating or interactive effects, therefore, were also examined. Because of the sample size and power issues, the effects of men’s and women’s antisocial behavior on men’s physical and psychological aggression toward their partner were tested in separate models from those examining the effects of the men’s and women’s depressive symptoms on the same outcomes.

Hypotheses were tested on the Oregon Youth Study (OYS) couples sample, which is a community sample of young men and their partners with at-risk backgrounds. Such couples are seriously underrepresented in community studies of partner aggression. Prior findings regarding the etiology of partner aggression in the sample are comparable to those of other community studies with a similar age group. The OYS Couples Study is unique, however, in having longitudinal partner aggression data, regardless of relationship changes. The present study also overcomes limitations in the literature by (a) incorporating a multiagent and multimethod approach with self- and partner report on aggression toward a partner as well as observational data rather than using self-report only and (b) employing more sophisticated longitudinal modeling approach (i.e., multilevel growth curve analysis) to take into account the interdependence of men’s and women’s behavior in a dyadic relationship.

Method

Participants

The present study used data from the Couples Study of a community sample of young couples with at-risk backgrounds. The men in the study were originally recruited for the OYS through fourth-grade classes (ages 9 – 10 years) in randomly selected public schools in higher crime areas of a medium-size metropolitan region in the Pacific Northwest. The men (n = 206) and their parents have been annually assessed since then, with the retention rate of 93% or above, over 2 decades. One hundred ninety one men (94% of 203 living participants) still remained as part of the panel in the 21st year of assessment. The sample was predominantly White (90%) and lower and working class (75%). Approximately 50% of the men had juvenile arrest records. Only 52% graduated from high school with their class. At age 20 – 21 years, 23% had been unemployed in the past year. In addition, 53 babies had been fathered by 43 (21%) of these young men by ages 20 – 21 years. By ages 30 – 31 years, 129 (63%) of the OYS men had fathered 263 children. All of these characteristics indicate the low socioeconomic status (SES) and risk status of the sample.

When the men were ages 17 – 18 years, the Couples Study started to examine the OYS men and their intimate partners’ adjustment in young adulthood. The men and their partners were assessed six times so far: late adolescence (Time 0 [T0], ages 17 – 20 years), young adulthood (Time 1 [T1], ages 20- 23 years), and early adulthood (Time 2 [T2], ages 23 – 25 years; Time 3 [T3], ages 25 – 27 years; Time 4 [T4], ages 27 – 29 years; and Time 5 [T5], ages 29 – 31 years). One hundred and nineteen men participated at T0, 158 at T1, 148 at T2, 161 at T3, 158 at T4, and 162 at T5. A total of 194 men participated in the Couples Study at least once over the study period. Because many of the OYS men were not in a steady relationship and measures on aggression toward a partner were limited at T0, the present study included data from T1 through T5. Demographic information for the participants at each time point is presented in Table 1. Note that the sample size varies over the study period because the OYS men’s intimate relationships changed over time, and some men were not in a steady relationship at the time of a particular assessment wave. Proportions of the men who completed the Couples Study assessment with the same partner as the previous assessment are presented in the Table 1. A total of 43 men completed all five assessments with the same partner.

Table 1. Descriptive Information for Couples Time 1 – Time 5.

| Time 1 n = 158 | Time 2 n = 148 | Time 3 n = 161 | Time 4 n = 158 | Time 5 n = 162 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men’s Age (M, SD) | 21.28 ( .88) | 24.10 ( .65) | 26.15 ( .61) | 28.08 ( .61) | 30.03 ( .56) |

| Women’s Age (M, SD) | 20.79 (3.39) | 23.14 (3.84) | 24.89 (4.04) | 26.08 (4.19) | 27.98 (4.37) |

| Same partner as previous wave | 23% | 38% | 49% | 53% | 78% |

| Relationship status | |||||

| Dating | 45% | 28% | 20% | 21% | 18% |

| Living together | 37% | 37% | 38% | 33% | 30% |

| Married | 18% | 35% | 42% | 46% | 52% |

| Relationship length (Weeks) | 82.88 (73.71) | 148.38 (117.88) | 180.62 (147.18) | 215.91 (167.30) | 272.36 (197.95) |

| Children in home | 18% | 30% | 35% | 39% | 41% |

| Men’s Relationship Satisfaction | 107.90 (19.36) | 106.63 (19.18) | 111.98 (15.99) | 110.47 (18.52) | 110.38 (16.69) |

| Women’s Relationship Satisfaction | 107.85 (16.44) | 108.13 (19.24) | 114.10 (16.78) | 109.51 (19.82) | 111.99 (19.56) |

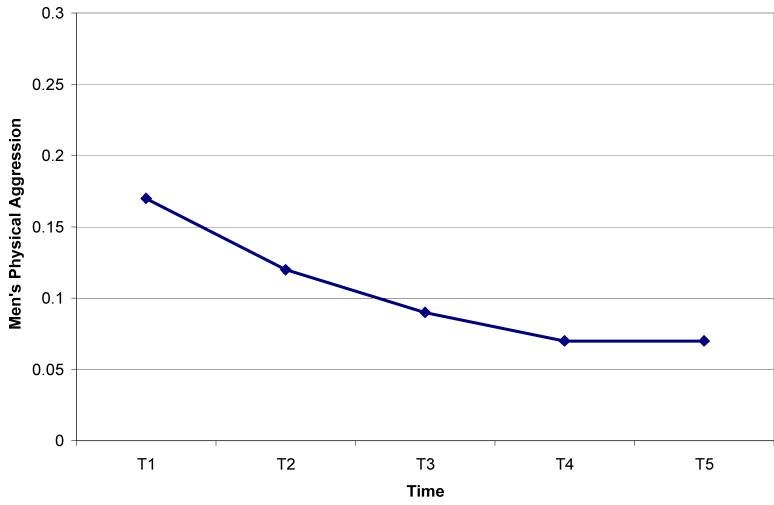

| Men’s Physical Aggression (0 – 3 scale) | 0.17 (.26) | 0.12 (.22) | 0.09 (.19) | 0.07 (.15) | 0.07 (.14) |

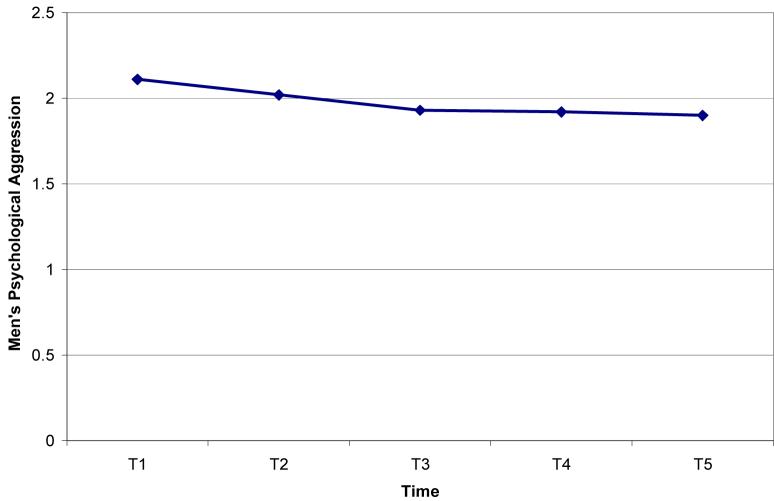

| Men’s Psychological Aggression (1 – 5 scale) | 2.11 (.66) | 2.02 (.67) | 1.93 (.60) | 1.92 (.64) | 1.90 (.60) |

| Men’s Depressive Symptoms | 7.44 (6.14) | 8.06 (7.97) | 7.66 (7.58) | 7.35 (7.25) | 8.62 (8.89) |

| Women’s Depressive Symptoms | 13.97 (10.12) | 13.36 (10.82) | 10.56 (8.24) | 11.78 (9.75) | 9.87 (9.98) |

Note: Values in the table represent means unless otherwise noted. Numbers in parentheses are standard deviations. Means and standard deviations of men’s and women’s antisocial behavior were not included in the table. This is because the antisocial behavior construct consisted of self-report and partner report, as well as observational data, and these indicators were standardized to be mean of 0 and standard deviation of 1 before they were combined to get the final construct score.

Procedures

Assessment for the OYS included separate interviews with parents and the young men; self-, parent-, and teacher-report questionnaires; interviewer and coder ratings; and court and Department of Motor Vehicle records; observed interaction tasks; telephone interviews; and peer-report data As the OYS men aged over time, teacher report was no longer collected after the ages of 17 – 18 years, and parent reports were confined to areas of adjustment of which they might have knowledge. Assessment for the Couples Study included a separate interview and questionnaires for the men and their partners and a series of videotaped discussion tasks. The entire Couples Study assessment lasted approximately 2 hr. For the present study, coding of five discussion tasks (excluding the warm-up task) was used, including party planning (5 min), partner’s issue (7 min for each partner’s issue), and goal discussion (5 min for each partner’s goal). For further information regarding the discussion tasks, see Capaldi and Crosby (1997) and Capaldi et al. (2003).

Measures

The constructs used in the present study included the OYS men’s and their partners’ physical and psychological aggression over time and both partners’ antisocial behavior and depressive symptoms from each time point. To maximize the advantage of the multiagent and multimethod approach, but to avoid the inflation of the Type I error rate secondary to multiple comparisons, constructs were developed with several indicators on the basis of the general construct-building strategy that has been used with the OYS (see Patterson & Bank, 1986). We first identified several variables a priori that were potential indicators of a given construct. Items within each scale were analyzed to check for internal consistency, and items included in the scale had to show an acceptable level of internal consistency (an item-to-total correlation greater than .20 and an alpha of .60 or higher). Then, each scale was examined for convergence with other scales designed to assess the same construct (i.e., the factor loading for a one-factor solution had to be .30 or higher, unless otherwise indicated). Once scales met these reliability criteria, they were combined to form a construct. Observational indicators for psychological and physical aggression tend to show slightly lower levels of internal consistency. Aggression during the observations was not necessarily expected to show significant association with self- and partner reports because of the limited time sampling of behavior (Kim & Capaldi, 2004) but met a priori definitions of aggression. All the indicators were retained, therefore, even if some of their intercorrelations were lower than our criteria. Another exception was the antisocial behavior construct for women. Because of relatively low frequencies for some items, internal consistencies for the women’s self-report indicator were somewhat lower than those of men’s at some time points. Sample items and internal reliability values for each indicator are described in Table 2. Data for the OYS men were taken from the corresponding year in which the couples’ assessment was collected (e.g., if the T1 Couples Study assessment was conducted in the OYS Year 12, the young men’s data were taken from the Year-12 assessment).

Table 2. Psychometric Properties of Measures.

| Construct and measure | No. of items | Sample items | Internal consistency |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physical aggression | |||

| Self-report | Men α = .62 – .83 Partner α = .72 – .81 | ||

| Adjustment with Partner (Kessler, 1990) | 2 | When disagree, how often do you push, grab, shove, throw something at partner, slap, or hit? | |

| Dyadic Social Skills Questionnaire (Capaldi, 1994) | 1 | You sometimes hurt your partner (e.g., hit partner or twist partner’s arm)? | |

| Conflict Tactics Scale (Straus, 1979) | 6 | Threw something at the partner. | |

| Partner report | Men α = .73 – .87 Partner α = .68 – .83 | ||

| Adjustment with Partner (Kessler, 1990) | 2 | When disagree, how often does partner push, grab, shove, throw something at you, slap, or hit? | |

| Interview | 1 | How many times has your partner hurt you? | |

| Dyadic Social Skills Questionnaire (Capaldi, 1994) | 1 | Your partner sometimes hurts you (e.g., hit or twist your arm)? | |

| Conflict Tactics Scale (Straus, 1979) | 6 | Threw something at you. | |

| Coder report | Men r = .14 – .52 Partner r = .41 – .59 | ||

| Coder impression rating | 4 | Displayed push, grab, or shove during task. | |

| Coded physical aggression (FPP Code; Stubbs et al., 1998) | NA | Rate per minute of aversive physical content during task. | |

| Psychological aggression | |||

| Self-report | Men α = .63 – .83 Partner α = .52 – .82 | ||

| Dyadic Social Skills Questionnaire (Capaldi, 1994) | 10 | Say mean things about your partner behind your partner’s back. | |

| Conflict Tactics Scale (Straus, 1979) | 6 | Yelled or insulted partner. | |

| Interview | 1 | Name calling, threats, sulking, or refusing to talk, screaming or cursing, throwing or breaking something [not at partner]? | |

| Adjustment with Partner (Kessler, 1990) | 1 | When disagree, how often do you insult or swear, sulk or refuse to talk, stomp out of the room, threaten to hit? | |

| Partner report | Men α = .61 – .87 Partner α = .67 – .89 | ||

| Adjustment with Partner (Kessler, 1990) | 4 | When disagree, how often does your partner insult or swear, sulk or refuse to talk, stomp out of the room, threaten to hit? | |

| Dyadic Social Skills Questionnaire (Capaldi, 1994) | 10 | Your partner blames you when something goes wrong. | |

| Partner Interaction Questionnaire (Capaldi, 1994) | 17 | Broken or damaged something of yours on purpose? | |

| Conflict Tactics Scale (Straus, 1979) | 6 | Yelled or insulted you. | |

| Interview | 1 | Name calling, threats, sulking or refusing to talk, screaming or cursing, throwing or breaking something [not at you]? | |

| Coder report | Men r = .52 – .62 Partner r = .53 – .60 | ||

| Coder impression rating | 11 | Was derogatory, sarcastic to partner in task, or called partner in task negative names (e.g., you jerk, dummy). | |

| Coded psychological aggression (FPP Code; Stubbs et al., 1998) | NA | Rate per minute of negative interpersonal, verbal attack, and coercive behavior. | |

| Antisocial behavior | |||

| Self-report | Men α = .70 – .75 Partner α = .43 – .75 | ||

| Elliott Behavior Checklist (Elliott, 1983) | 38 for men 16 for partner | How many times in the last 12 months have you bought or sold stolen goods? | |

| Self- or partner report (self-report by men; men’s report on partner) | Men α =.90 – .92 Partner α = .80 – .89 | ||

| Young Adult Behavior Checklist (Achenbach, 1997) | 29 for men 30 for partner | I don’t (partner doesn’t) feel guilty after doing things I (partner) shouldn’t. | |

| Coder report | Men α = .66 – .84 Partner α = .71 – .83 | ||

| Coder impressions | 3 | Seemed antisocial or delinquent. |

Note: Internal consistency and correlation ranges for aggression indicators are for Time 1 – Time 5. FPP = Family and Peer Process. NA = not applicable.

Coding of the interaction tasks

The Family and Peer Process Code (FPPC; Stubbs, Crosby, Forgatch, & Capaldi, 1998) was used to code the interaction tasks at each wave. A computer was used to record, in real time, the interpersonal behavioral and emotive content of each couple’s interaction. The 24 content codes included verbal, vocal, nonverbal, physical, and compliance behaviors that were judged a priori as having a positive, neutral, or negative impact. For physical behavior, affectionate touch and embrace were coded as positive, behaviors such as grooming and physical play were coded as neutral, and physical aggression was coded as negative. Six affective ratings described the participant’s emotional tone in terms of distinct types of emotional displays, namely, happy, caring, neutral, distress, aversive, and sad. An affect rating was assigned to each content code on the basis of tone and inflection of voice, body posture, nonverbal gestures, and facial expressions. Because content code and affect code definitions were independent of each other (i.e., any affect code could qualify any content code), playful teasing or joking behaviors might be coded with negative content and positive affect. To assess coder reliability at each time point, approximately 15% of the tasks were randomly selected to be coded independently by two coders. The overall content and affect kappas at each time point ranged from .73 to 85. All coders were professional research assistants. Initial coder training took approximately 3 months.

Men physical aggression

The physical aggression construct was composed of items from the interviews, questionnaires, discussion tasks, and coder impressions. Items from interviews and questionnaires included both self- and partner’s reports (Table 2). For the observed physical aggression indicator, the overall rate per minute of two content codes (physical aversive and physical aggression) in four affects (neutral, distress, aversive, and sad) was included from the FPPC coding of the interaction task. The same items were included for the indicators at T1 – T5. Self-reported physical aggression tended to be associated with partner reports, r = .31 – .60, across waves. Men’s self-reports of physical aggression were also significantly correlated with observed aggression, r = .18 – .60, across waves, except for T4, r = .05.

Men psychological aggression

The psychological aggression construct was developed with items from the interviews, questionnaires, discussion tasks, and coder impressions. Similar to physical aggression, the OYS men and their partners reported on men’s psychological aggression and the same items were included across T1 through T5 (Table 2). For the observed psychological aggression measure, the overall rate per minute of three content codes (negative interpersonal, verbal attack, and coerce) in four affects (neutral, distress, aversive, and sad) was used from the FPPC coding of the interaction task. Self-reported psychological aggression tended to be significantly associated with partner reports, r = .47 – .55, and with observed data, r = .23 – .55, across waves.

Men and women’s antisocial behavior

Three indicators were used to measure men’s antisocial behavior, including self-reports on the Elliott Behavior Checklist (Elliott, 1983) and Young Adult Behavior Checklist (Achenbach, 1997) and coder impressions. Women’s antisocial behavior construct included self-reports on the Elliott Behavior Checklist, partner reports on the Young Adult Behavior Checklist, and coder impressions. To avoid content overlap with the partner aggression constructs, items involving aggression toward a partner or family members were not included in this construct. The men’s two self-reports of antisocial behavior were significantly related, r = .36 – .43, across instruments and waves, and relationships between these and coder reports were variable, r = .10 – .40, across waves. Women’s self-reported antisocial behavior showed variable associations with partner reports of the women’s behavior, r = .08 – .34, and coder reports tended to relate to self-report, r = .24 – .45, and partner reports r = .26 – .38.

Men and women’s depressive symptoms

For the OYS men and their partners, a 20-item self-report scale of depressive symptoms (CES-D; Radloff, 1977) was used as an indicator of depressive symptoms. For each item, the participant indicated how often they had experienced the symptom in the past week from 0 (rarely or none) to 3 (most or all the time). Internal consistency was high for men (alpha = .81 – .92) and women (alpha = .88 – .93) across waves. As indicated in Table 1, women tended to show higher symptom levels than men across time.

Relationship control variables

Several characteristics of the men’s relationships at each time point were included in the model as time-varying control variables. These were on the basis of both partners’ reports from the Couples Study assessment at each of the Waves 1 – 5. For relationship stability, a dichotomous variable was computed to indicate whether the OYS man was participating with the same partner as at the previous time point (1) or not (0). For relationship status, an ordinal variable indicating greater commitment, ranging from dating (1), to living together (2), to married (3), was computed for each wave. A dichotomous variable indicating that the couple had children living in the home with them (1) or not (0) was assigned. Relationship satisfaction was computed with men’s and their partners’ scores on the Dyadic Adjustment Scale (Spanier, 1976). The Dyadic Adjustment Scale is a 32-item scale designed to measure satisfaction in intimate relationships and contains subscales for consensus, satisfaction, cohesion, and affection expression. The total scores for men and women were used separately in analyses. Note that in the preliminary analyses, the length of the relationship was not related to men’s aggression and thus was not considered in the further analyses. Means and standard deviations of men’s physical and psychological aggression and men’s and women’s depressive symptoms at each time point are presented in Table 1, along with summary statistics for relationship control variables.

Planned Analysis

Multilevel Growth Modeling with Hierarchical Linear Modeling was used to take into account the dependency of men’s aggression scores over time and also of partner characteristics within couples. At Level 1, within-couple variability in individual men’s aggression scores is modeled with an intercept (level at T1) and linear slope, as well as an error term reflecting variability not explained by the linear growth model. Level 2 models between-couple variability in men’s aggression intercept and slope terms. The focus of the present study was on the relationship between risk factors within the couple (men’s and women’s antisocial behavior and depressive symptoms) and men’s aggression over time; all prediction models, therefore, were tested at Level 1. The significant Level 1 time-varying covariates then would represent significant changes in men’s aggression associated with changes in men’s or women’s problem behavior. One of the advantages of focusing on this intracouple approach (i.e., Level 1 model) is that, by establishing within-couple variations between each partner’s problem behavior and men’s aggression toward a partner over time, the findings allow us to specify the dynamic nature of partner influence processes proposed in the DDS model.

In the following models, men’s and women’s antisocial or depressive symptom scores, as well as the interaction between their scores, were entered as time-varying covariates predicting men’s psychological or physical aggression from T1 – T5. Men’s and women’s antisocial behavior and depressive symptoms scores were centered prior to creating the interaction terms at each wave. Prior to entering these main study predictors, several characteristics of couples’ relationships at each time point were tested as possible controls (i.e., as time-varying covariates): relationship stability (same partner as previous wave: yes or no), relationship status (dating, living together, or married), children in the home (yes or no), and partners’ relationship satisfaction (men’s and women’s total scores on the Dyadic Adjustment Scale). For the sake of simplicity, only control variables that proved significant were included in the full models testing effects of partners’ antisocial behavior and depressive symptoms.

Results

On the basis of either partner’s report on the Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS), prevalence rates of any physical aggression by the men decreased substantially across time from 28% at T1 to 7% at T5. The prevalence of Conflict Tactics Scale psychological aggression, on the other hand, did not show a marked change over time, with the majority of men exhibiting some psychological aggression across the entire study period (72 – 76% of men from T1 – T5). Prevalence rates that are based on observations of couples’ interactions showed similar declines in men’s physical aggression – from 16% at T1 to 2% at T5 – alongside consistently high prevalence rates of psychological aggression – 71 – 84% from T1 to T5. Figure 1 and 2 represent the men’s mean levels of physical and psychological aggression over time on the basis of the construct scores, including reported and observational data. Overall, antisocial behavior and depressive symptoms of both members of the couple were significantly and positively related to men’s physical and psychological aggression (averaged over time). In addition, men’s and women’s antisocial behavior were associated across time points, r = .51 – .69, and men’s depressive symptoms were also significantly related to women’s symptoms at four of the five time points, r = .02 – .26. A full report on correlations among the study variables is available upon request.

For each of the two (continuous) aggression outcomes (i.e., physical and psychological aggression), the unconditional multilevel growth curve model (containing no predictors) was examined first; then the control variables were included in the model. The final models included antisocial behavior or depressive symptoms for both members of the couple, as well as interactions between the men’s and women’s problem behaviors and control variables that were significant in the previous step.

Men’s Physical Aggression Toward Women

The unconditional model established that men’s average level of physical aggression at T1 was relatively low (.15 on the 0 – 3 scale) and also decreased significantly from T1 – T5. Level 1 variability in men’s physical aggression that was not explained by the linear trajectory remained significant, σ2 = .02, SE = .001. Thus, changes in men’s physical aggression from one time point to the next could not be completely captured by a linear declining pattern. Time-varying predictors – control variables and both partners’ risk characteristics of interest – were added to predict variability.

Of the control variables tested, women’s relationship satisfaction at each wave related negatively to men’s physical aggression, meaning that higher partner satisfaction was associated with lower levels of men’s physical aggression. Relationship status was significantly and positively associated with men’s physical aggression: Men in more committed relationships tended to show higher levels of physical aggression. These two control variables were included in the subsequent model. Note that the partner stability variable (same or different partner as previous wave) and the presence of children were not related to men’s physical aggression; thus, they were not included in the further analysis.

Antisocial behavior

Men’s and women’s antisocial scores at each wave, as well as their interactions, were entered as predictors of men’s physical aggression. Only women’s antisocial behavior made a unique contribution to predicting men’s level of physical aggression at each wave, with no significant interaction indicating moderation of the effect (see Table 3, middle panel). In other words, higher levels of women’s antisocial behavior or increases in such behavior across time were associated with relatively higher levels of men’s physical aggression toward them at particular time points. The two control variables remained significant. The model showed a significant improvement in fit compared to the baseline model, χ2(5) = 45.50, p < .001.

Table 3. Model Results for Men’s Physical Aggression Outcome.

| Model | Baseline | Final | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antisocial Behavior | Depressive Symptoms | |||||

| Predictor | Coeff. (SE) | p | Coeff. (SE) | p | Coeff. (SE) | p |

| Level 1 Effects | ||||||

| Men’s Risk | .03 (.02) | .10 | .001 (.001) | .22 | ||

| Women’s Risk | .04 (.02) | .01 | .003 (.001) | .003 | ||

| Men x women Risk | -.004 (.009) | .67 | 3×10-6 (9×10-5) | .98 | ||

| Women’s DAS | -.002 (5×10-4) | .002 | -.001 (5×10-4) | .01 | ||

| Relationship status | .04 (.01) | .006 | .03 (.01) | .02 | ||

| Level 2 Parameters | ||||||

| Intercept (T1 Level) | .15 (.02) | < .001 | .16 (.02) | < .001 | .16 (.02) | < .001 |

| Slope (T1-T5) | -.02 (.005) | < .001 | -.03 (.006) | < .001 | -.03 (.006) | < .001 |

Note: DAS = relationship satisfaction measured by the Dyadic Adjustment Scale.

Depressive symptoms

Next, we examined effects of both partner’s depressive symptoms on men’s physical aggression toward the women. Again, the women’s depressive symptoms related to higher levels of the men’s physical aggression toward them, with no significant effects of the men’s own depressive symptoms and no moderational effect (see Table 3, right panel). Higher levels of women’s depressive symptoms, thus, were associated with relatively higher levels of men’s physical aggression at particular time points. Again, the two control variables remained significant. This model was significantly better fitting than the baseline model, χ2(5) = 20.28, p = .01.

Men’s Psychological Aggression Toward Women

Intercept and slope terms from the baseline model revealed that, on average, men displayed moderate levels of psychological aggression at T1 (2 on the 1 – 5 scale) and declined significantly from T1 – T5. Similar to men’s physical aggression, Level 1 variability in men’s psychological aggression, σ2 = .20, SE = .01, that was not explained by the linear trajectory remained significant, making the case for adding time-varying within-couple predictors. A test of possible control variables showed that both men’s and women’s relationship satisfaction was negatively related and relationship status was positively related to men’s psychological aggression. These two control variables, therefore, were retained in further model testing. Relationship stability and the presence of children did not relate to the men’s aggression and were not included in further analysis.

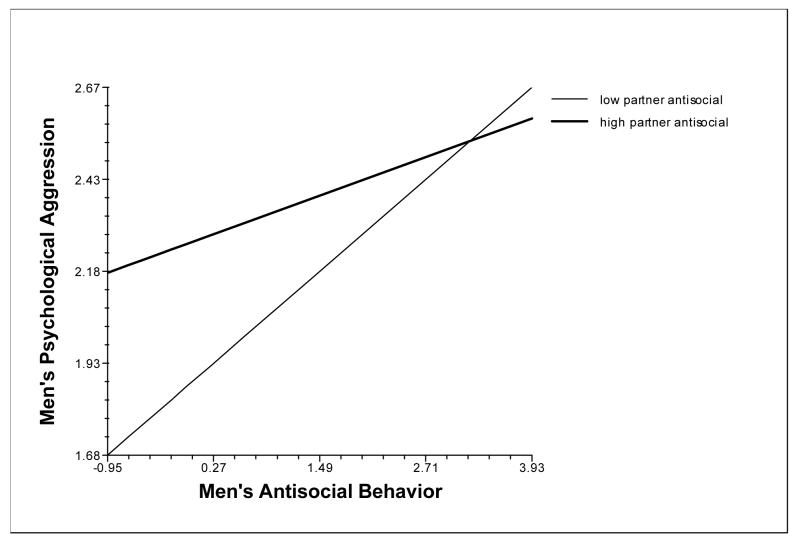

Antisocial behavior

When the men’s and women’s antisocial scores at each wave, as well as their interaction, were entered as predictors of men’s psychological aggression, all three terms proved significant (see Table 4, middle panel). Higher antisocial behavior on both the men’s and women’s part were associated with higher levels of men’s psychological aggression; a contrast of coefficients for these two main effects showed that the effect of the women’s antisocial behavior was even greater than that of the men’s, χ2(2) = 97.05, p < .001. The interaction effect additionally revealed that the impact of either partner’s antisocial behavior was greatest when the other’s was relatively low (see Figure 3). In other words, if the man was lower in antisocial behavior, being with an antisocial partner had a negative effect on his level of psychological aggression compared with being with a less antisocial partner. This model yielded a significant improvement in fit over baseline as judged by change in the deviance statistic, χ2(6) = 328.05, p < .001. All three control variables remained significant.

Table 4. Model Results for Men’s Psychological Aggression Outcome.

| Model | Baseline | Final | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antisocial Behavior | Depressive Symptoms | |||||

| Predictor | Coeff. (SE) | p | Coeff. (SE) | p | Coeff. (SE) | p |

| Level 1 Effects | ||||||

| Men’s Risk | .16 (.04) | < .001 | .006 (.003) | .02 | ||

| Women’s Risk | .22 (.03) | < .001 | .01 (.002) | < .001 | ||

| Men x Women Risk | -.07 (.02) | .002 | 1×10-4 (2×10-4) | .67 | ||

| Men’s DAS | -.009 (.002) | < .001 | -.01 (.002) | < .001 | ||

| Women’s DAS | -.007 (.001) | < .001 | -.006 (.001) | < .001 | ||

| Relationship status | .22 (.03) | < .001 | .22 (.03) | < .001 | ||

| Level 2 Parameters | ||||||

| Intercept (T1 Level) | 2.05 (.05) | < .001 | 2.13 (.04) | < .001 | 2.11 (.04) | < .001 |

| Slope (T1-T5) | -.04 (.01) | .006 | -.06 (.01) | < .001 | -.06 (.01) | < .001 |

Note: DAS = relationship satisfaction measured by the Dyadic Adjustment Scale.

Depressive symptoms

Of the three prediction terms entered – the men’s and women’s depressive symptoms scores and the interaction of their scores – only the main effects proved significant (see Table 4, right panel). Thus, higher levels of either partner’s depressive symptoms were related to higher levels of the men’s psychological aggression at individual time points. Similar to the effects for antisocial behavior, the women’s depressive symptoms were more strongly related to his aggression toward her than were his own depressive symptoms, χ2(2) = 34.89, p < .001. The model improved significantly in fit over baseline, χ2(6) = 268.53, p < .001. Again, all three control variables remained significant.

Overall, the results of the within-couple prediction models described above pointed to both partners’ (but especially the women’s) antisocial behavior and depressive symptoms as contributors over time to men’s psychological aggression toward women. For men’s physical aggression, it was only the women’s risk factors that uniquely related to increasing or decreasing aggression. Although men tended to show a pattern of desistance in aggression across the 10-year time period studied, these characteristics of themselves and their partner explained additional variability in aggression not captured by the overall linear (declining) trajectory.

Discussion

Findings of the present study indicated that the prevalence rates of men’s physical aggression toward a partner assessed by combined self- and partner reports and observational data decreased significantly across a 10-year period from approximately ages 21 to 30 years. Multilevel Growth Modeling confirmed a significant downward linear slope for levels of physical violence in this sample of young men from at-risk backgrounds, despite the fact that many experienced changes in relationships and partners over time. Similarly, men’s levels of psychological aggression decreased significantly over time, although the prevalence of any such aggression was relatively stable when it was based on either partner’s reports on the CTS. The occurrence of at least some psychological aggression was very common in the sample. It is noteworthy that young men tended to have higher prevalence rates of physical and psychological aggression when this was based on observed data than based on combined self- and partner’s reports. This may indicate that young couples commonly show a variety of negative behaviors that were captured as physical or psychological aggression by our FPPC coding system but they do not necessarily view such behaviors as aggression (i.e., verbal attacks, such as ‘You’re a jerk,’ in negative affect). Overall, our findings are consistent with other studies with community and national survey samples that have shown a high level of aggression in the men’s early 20s and a pattern of significant desistance over time, regardless of its severity (e.g., Fritz & O’Leary, 2004; O’Leary & Woodin, 2005). At the same time, this finding contradicts the early argument that men’s aggression toward a partner becomes worse over time (e.g., Pagelow, 1981).

Significant associations between partners for both antisocial behavior and depressive symptoms confirmed previous findings regarding assortative partnering by these risk characteristics (e.g., Kim & Capaldi, 2004). These findings support the argument that potential partner effects and social influence processes within the dyad should be considered of great importance in studying aggression in couples, as in other areas of couples’ functioning. Findings confirmed the hypothesis that partners’ risk characteristics would play a significant role in men’s physical and psychological aggression. In particular, antisocial behavior by both men and women related to changes in levels of men’s psychological aggression toward a partner. Interestingly, effects of women’s antisocial behavior on men’s aggression were significantly stronger than men’s own antisocial behavior, despite that the construct for women’s antisocial behavior consisted of fewer items and thus was slightly weaker than for the men’s. Women’s depressive symptoms, furthermore, exerted a significant main effect on the level of men’s physical and psychological aggression. Studies have consistently indicated that couples with a depressed spouse (typically a depressed wife) show various interactional difficulties, including elevated levels of hostility, sad affect, lack of affection, and negative communication styles (McCabe & Gotlib, 1993). This finding extends that of a previous study (Kim & Capaldi, 2004) that showed the relatively strong concurrent and longitudinal effects of women’s depressive symptoms on men’s physical and psychological aggression toward a partner in the early 20s. In the previous study, couples who remained stable over two time points were examined. The present study indicates that depressed partners’ influence on men’s aggression hold true over an extended period of time. The present findings also indicated that men’s depressive symptoms were also significantly related to his psychological aggression. It is not clear from the present study, however, why women’s depressive symptoms exerted stronger influence on men’s psychological aggression than did his own depressive symptoms. Although many studies have sought to address the link between depression and relationship adjustment, the mechanisms by which partners’ depressive symptoms influence specific aspects of couples’ interaction or affective processes, which in turn lead to aggression, remain unclear. In the present study, prediction from antisocial behavior and depressive symptoms was tested in separate models because of the limited sample size. The predictive effects of one problem domain controlling for the other could not be tested. Given that both problem behaviors tend to co-occur quite commonly (e.g., Capaldi, 1991), a more thorough investigation of the role of depressed partners is needed.

A substantial contribution of the present study was the confirmation of significant interaction effect of men’s and women’s antisocial behavior on men’s psychological aggression over time. The effect, however, was rather different from what was expected. When men showed higher levels of antisocial behavior, the level of his partner’s antisocial behavior did not seem to add to his risk for psychological aggression toward a partner. On the other hand, when men had relatively low levels of antisocial behavior, having a partner with high levels of antisocial behavior was significantly related to increases in men’s psychological aggression from one time point to the next. Thus, rather than additional interactive risk because of high levels of antisocial behavior in both men and women, men who were lower in antisocial behavior seemed vulnerable to negative effects from a partner with higher levels of antisocial behavior. The findings, overall, demonstrate that partners’ characteristics constitute a significant influence on men’s aggression toward a partner. Although it seems intuitive to believe that individuals’ characteristics and social processes within the dyad influence the interpersonal dynamics of couples, including partner aggression, approaches that do not take a one-sided, male-only view of partner aggression have been discouraged. Findings from the present study, however, indicate that both partners’ characteristics and social processes within the dyad might be the key proximal factor for understanding and preventing aggression within the couples, especially in early adulthood.

Of the contextual factors considered in the present study, women’s relationship satisfaction was associated with decreases in men’s physical and psychological aggression, whereas men’s relationship satisfaction was associated with decreases in his psychological aggression only. This finding is in line with previous research that showed a close relationship between relationship satisfaction and aggression toward a partner (e.g., Rogge & Bradbury, 1999). It should be noted that our finding does not necessarily indicate a causal pathway. Rather, it may indicate the bidirectional nature of the association between relationship satisfaction and aggression toward a partner. Our finding further indicated that more committed relationship status was associated with increases in levels of both forms of aggression. This may have to do, in part, with the fact that living together (either being married or cohabiting) brings up much more in the way of daily problems, such as sharing household chores or money. This may provide more contexts in which arguments and disagreement can occur. This finding, however, is somewhat inconsistent with Stets and Straus’s (1989) finding that cohabiting couples had higher rates of physical aggression toward a partner than the married or dating couples. According to our preliminary study, overall, being married was associated with higher levels of aggression than cohabiting or dating. Stets and Straus argued that married couples might be less violent than cohabiting couples because the cost of aggression toward a partner is greater for married couples and thus they may be more constrained to avoid aggression. It is possible that most of the couples in the current sample were from at-risk backgrounds, and, because married couples were more likely to have children, they might face significant chronic stress because of limited resources. Replication work with independent samples is warranted to further examine the effects of relationship status on men’s aggression over time.

Another noteworthy finding is that men’s psychological aggression, which showed a higher prevalence than physical aggression, may have a different developmental course and related mechanisms than those of physical aggression; both men and women’s characteristics (antisocial behavior and depressive symptoms) exerted significant effects in changes in men’s psychological aggression, whereas only women’s risk characteristics were predictive of changes in men’s physical aggression. Jacobson et al. (1996) have argued that men’s physical aggression may decrease with age, although emotional abuse would remain high, because once power dynamics have been established within the dyad, physical aggression might not be necessary to maintain them. Men’s psychological aggression, however, tended to decrease across time in the present study. The patterns of association between two types of aggression over time and common and specific factors warrant further attention.

Even though the men’s aggression toward a partner substantially decreased over young adulthood, nonnegligible rates of such violence are still present among men as they enter middle adulthood. The present study did not include outcomes such as injuries or sexual coercion. Measures of other aspects of violence toward a partner might show differing patterns over time from those found in the present study. Furthermore, men included in the study were representative of the areas from which they were recruited in being predominantly White and of lower SES. The extent to which findings from the present study would generalize to samples with differing characteristics, however, should be tested. In addition, the present study used a dimensional approach and did not make any distinctions among different types or levels of aggression within each aggression outcome. It is possible that those men who showed frequent acts of moderate physical assaults (i.e., pushing or grabbing) early on progressed to severe acts of aggression (i.e., beating up) toward a partner, but less frequently. These kinds of cases might have been viewed as decreasing over time, which may be somewhat misleading. Future research would benefit from a more fine-grained approach to distinguish different types of violent acts. Finally, the present study did not test gender differences in the partner’s role in the developmental trajectories of partner aggression. Our study was designed to follow men, rather than couples; men, therefore, were allowed to participate with different partners over time. This is a unique aspect of our study, but at the same time, this precluded us from examining women’s trajectories more systematically. Gender differences in the aggression trajectories and associated mechanisms need more systematic research.

Nonetheless, the present study is unique in the field and represents a number of advantages by (a) including couples across relationships without excluding those who dissolved the relationship, (b) examining an extended period of young adulthood (across the ages of early 20s through early 30s), and (c) providing a strong developmental dynamic focus, which is rarely considered by most studies in the field. The present study also showed that the partner’s characteristics do play a prominent role in predicting men’s aggression toward a partner, over and above his own risk characteristics. Although more research is needed to further illuminate couples’ social influence processes, our findings provide valuable insights into the developmental trajectories of young men’s aggression toward a partner over an extended period of time and underscore the importance of studying social processes within the dyad. In the next step, we will try to extend the present study by including other factors to explain between-couple variations in men’s aggression trajectories over time.

In summary, previous studies that were based on only men’s behavior provided little insight into the developmental processes of aggression over time. We believe that our findings, which are based on the DDS perspective, are in line with growing interest in the interactional perspective on aggression in couples (e.g., Lawrence & Bradbury, 2007; Straus, 2006; Winstok, 2007). Consistent with Schumacher and Leonard’s (2005) study, our findings provide potential implications for intervention efforts at the level of the dyad. There is growing evidence that dyadic-based treatment can be an effective alternative intervention model to reduce aggression in couples (O’Leary, Heyman, & Neidig, 1999; O’Leary & Slep, 2003). Most of all, aggression in intimate relationships often occurs during conflicts between partners (e.g., Cascardi & Vivian, 1995). Capaldi, Kim, and Shortt (2007) found that a verbal argument had preceded the domestic violence in 88% of incidents that resulted in arrest. In addition, as described earlier, aggression in couples is often mutual and reciprocal (Whitaker, Haileyesus, Swahn, & Saltzman, 2007), especially among young couples (Capaldi et al. 2007). Furthermore, relationship conflict or discord is one of the strongest risk factors for aggression toward a partner (e.g., Pan et al., 1994). In fact, relationship separation or dissolution may be a key context associated with a substantial proportion of domestic violence arrests (Capaldi et al. 2007). As Straus (2006) argued, the field needs new prevention and treatment modalities with more balanced attention to behaviors of both members of the couple. Acknowledging the possibility that both partners contribute to the couples dynamic does not shift the blame away from the perpetrator. Rather, assessing both partners’ level of aggression and risk factors, as well as other interactional patterns within the dyad, will inform clinicians and may allow for more comprehensive and effective violence prevention and intervention efforts. We hope that our findings will motivate further research uncovering the processes by which both partners’ characteristics ignite or inhibit aggression in relationships.

Acknowledgments

The Cognitive, Social, and Affective Development Branch, National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD) and Division of Epidemiology, Services, and Prevention Branch, National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), National Institutes of Health (NIH), U.S. Public Health Service (PHS) provided support for the Couples Study (Grant HD 46364). Additional support was provided by Grant MH 37940 from the Psychosocial Stress and Related Disorders Branch, National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), U.S. PHS and Grant DA 051485 from the Division of Epidemiology, Services and Prevention Branch, NIDA, and Cognitive, Social, and Affective Development, NICHD, NIH, U.S. PHS.

We thank Jane Wilson, Rhody Hinks, and the data collection staff for their commitment to high quality data and Sally Schwader for editorial assistance with manuscript preparation.

References

- Achenbach TM. Manual for the Young Adult Self-Report and Young Adult Behavior Checklist. University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry; Burlington: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Aldarondo E. Cessation and persistence of wife assault: A longitudinal analysis. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1996;66:141–151. doi: 10.1037/h0080164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews JA, Foster SL, Capaldi DM, Hops H. Adolescent and family predictors of physical aggression, communication, and satisfaction in young adult couples: A prospective analysis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68:195–208. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.68.2.195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Archer J. Sex differences in aggression between heterosexual partners: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin. 2000;126:651–680. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.126.5.651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM. Co-occurrence of conduct problems and depressive symptoms in early adolescent boys: I. Familial factors and general adjustment at 6th Grade. Development and Psychopathology. 1991;3:277–300. doi: 10.1017/s0954579499001959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM. Dyadic Social Skills Questionnaire. Oregon Social Learning Center; Eugene: 1994. Unpublished Questionnaire. [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM, Clark S. Prospective family predictors of aggression toward female partners for at-risk young men. Developmental Psychology. 1998;34:1175–1188. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.34.6.1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM, Crosby L. Observed and reported psychological and physical aggression in young, at-risk couples. Social Development. 1997;6:184–206. [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM, Kim HK. Typological approaches to violence in couples: A critique and alternative conceptual approach. Clinical Psychology Review. 2007;27:253–265. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2006.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM, Kim HK, Owen LD. Romantic partners’ influence on men’s likelihood of arrest in early adulthood. Criminology. 2008;46:401–433. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-9125.2008.00110.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM, Kim HK, Shortt JW. Observed initiation and reciprocity of physical aggression in young, at-risk couples. Journal of Family Violence. 2007;22:101–111. doi: 10.1007/s10896-007-9067-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM, Shortt JW, Crosby L. Physical and psychological aggression in at-risk young couples: Stability and change in young adulthood. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly. 2003;49:1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Capaldi DM, Shortt JW, Kim HK. A life span developmental systems perspective on aggression toward a partner. In: Pinsof WM, Lebow J, editors. Family psychology: The art of the science. Oxford University Press; New York: 2005. pp. 141–167. [Google Scholar]

- Cascardi M, Vivian D. Context for specific episodes of marital violence: Gender and severity of violence differences. Journal of Family Violence. 1995;10:265–293. [Google Scholar]

- Casey BJ, Tottenham N, Liston C, Durston S. Imaging the developing brain: What have we learned about cognitive development? Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2005;9:104–110. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2005.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleveland HH, Herrera VM, Stuewig J. Abusive males and abused females in adolescent relationships: Risk factor similarity and dissimilarity and the role of relationship seriousness. Journal of Family Violence. 2003;18:325–339. [Google Scholar]

- Dishion TJ, Eddy JM, Haas E, Li F, Spracklen K. Friendships and violent behavior during adolescence. Social Development. 1997;6:207–225. [Google Scholar]

- Dutton DG. The origin and structure of the abusive personality. Journal of Personality Disorders. 1994;8:181–191. [Google Scholar]

- Elliott DS. Interview schedule, National Youth Survey. Behavioral Research Institute; Boulder, CO: 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Feld SL, Straus MA. Escalation and desistance from wife assault in marriage. In: Straus MA, Gelles RJ, editors. Physical violence in American families: Risk factors and adaptations to violence in 8,145 families. Transaction; New Brunswick, NJ: 1990. pp. 489–505. [Google Scholar]

- Follingstad DR, Rutledge LL, Berg BJ, Hause ES, Polek DS. The role of emotional abuse in physically abusive relationships. Journal of Family Violence. 1990;5:107–120. [Google Scholar]

- Fritz PA, O’Leary KD. Physical and psychological aggression across a decade: A growth curve analysis. Violence and Victims. 2004;19:3–16. doi: 10.1891/088667004780842886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelles RJ, Straus MA. Intimate violence: The causes and consequences of abuse in the American family. Simon and Schuster; New York: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Holtzworth-Munroe A, Stuart GL. Typologies of male batterers: Three subtypes and the differences among them. Psychological Bulletin. 1994;116:476–497. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.116.3.476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson NS, Gottman JM, Gortner E, Berns S, Shortt JW. Psychological factors in the longitudinal course of battering: When do the couples split up? When does the abuse decrease? Violence and Victims. 1996;11:371–392. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keenan-Miller D, Hammen C, Brennan P. Adolescent psychosocial risk factors for severe intimate partner violence in young adulthood. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2007;75:456–463. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.3.456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC. The national comorbidity survey. DIS Newsletter. 1990;7(12):1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Kim HK, Capaldi DM. The association of antisocial behavior and depressive symptoms between partners and risk for aggression in romantic relationships. Journal of Family Psychology. 2004;18:82–96. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.18.1.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence E, Bradbury TN. Physical aggression and marital dysfunction: A longitudinal analysis. Journal of Family Psychology. 2001;15:135–154. doi: 10.1037//0893-3200.15.1.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence E, Bradbury TN. Trajectories of change in physical aggression and marital satisfaction. Journal of Family Psychology. 2007;21:236–247. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.21.2.236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorber MF, O’Leary KD. Predictors of the persistence of male aggression in early marriage. Journal of Family Violence. 2004;19:319–338. [Google Scholar]

- Magdol L, Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Silva PA. Developmental antecedents of partner abuse: A prospective longitudinal study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1998;107:375–389. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.107.3.375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall AD, Holtzworth-Munroe A. Varying forms of husband sexual aggression: Predictors and subgroup differences. Journal of Family Psychology. 2002;16:286–296. doi: 10.1037//0893-3200.16.3.286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe SB, Gotlib IH. Interactions of couples with and without a depressed spouse: Self-report and observations of problem-solving situations. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 1993;10:589–599. [Google Scholar]

- Mihalic SW, Elliott DA, Menard S. Continuities in marital violence. Journal of Family Violence. 1994;9:195–225. [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt T, Caspi A, Rutter M, Silva PA. Sex, antisocial behavior, and mating: Mate selection and early childbearing. In: Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Rutter M, Silva PA, editors. Sex differences in antisocial behavior: Conduct disorder, delinquency, and violence in the Dunedin longitudinal study. Cambridge University Press; New York: 2001. pp. 184–197. [Google Scholar]

- O’Leary KD. Developmental and affective issues in assessing and treating partner aggression. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 1999;6:400–414. [Google Scholar]

- O’Leary KD, Heyman RE, Neidig PH. Treatment of wife abuse: A comparison of gender-specific and conjoint approaches. Behavior Therapy. 1999;30:475–505. [Google Scholar]

- O’Leary KD, Malone J, Tyree A. Physical aggression in early marriage: prerelationship and relationship effects. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1994;62:594–602. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.62.3.594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Leary KD, Slep AMS. A dyadic longitudinal model of adolescent dating aggression. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2003;32:314–327. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3203_01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Leary KD, Woodin EM. Partner aggression and problem drinking across the lifespan: How much do they decline? Clinical Psychology Review. 2005;25:877–894. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pagelow M. Woman-battering: Victims and their experiences. Sage; Newbury Park, CA: 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Pan HS, Neidig PH, O’Leary KD. Predicting mild and severe husband-to-wife physical aggression. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1994;62:975–981. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.62.5.975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patterson GR, Bank L. Bootstrapping your way in the nomological thicket. Behavioral Assessment. 1986;8:49–73. [Google Scholar]

- Quigley BM, Leonard KE. Desistance of husband aggression in the early years of marriage. Violence and Victims. 1996;11:355–370. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinton D, Pickles A, Maughan B, Rutter M. Partners, peers, and pathways: Assortative pairing and continuities in conduct disorder. Special Issue: Milestones in the development of resilience. Development and Psychopathology. 1993;5:763–783. [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D Scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychological Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- Rhule-Louie DM, McMahon RJ. Problem behavior and romantic relationships: Assortative mating, behavior contagion, and desistance. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2007;10:53–100. doi: 10.1007/s10567-006-0016-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riggs DS, O’Leary KD. A theoretical model of courtship aggression. In: Pirog-Goood MA, Stets JE, editors. Violence in dating relationships: Emerging social issues. Praeger; New York: 1989. pp. 53–71. [Google Scholar]

- Robins RW, Caspi A, Moffitt TE. Two personalities, one relationship: Both partners’ personality traits shape the quality of their relationship. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2000;79:251–259. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.79.2.251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogge RD, Bradbuy TN. Till violence does us part: The differing roles of communication and aggression in predicting adverse marital outcomes. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1999;67:340–351. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.67.3.340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampson RJ, Laub JH. Life-course desisters? Trajectories of crime among delinquent boys followed to age 70. Criminology. 2003;41:555–592. [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher JA, Leonard KE. Husbands’ and wives’ marital adjustment, verbal aggression, and physical aggression as longitudinal predictors of physical aggression in early marriage. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73:28–37. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.1.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spanier GB. Measuring dyadic adjustment: New scales for assessing the quality of marriage and similar dyads. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1976;38:15–28. [Google Scholar]

- Stets JE, Straus M. The marriage license as a hitting license: A comparison of assaults in dating, cohabiting and married couples. Journal of Family Violence. 1989;4:161–180. [Google Scholar]

- Stith SM, Smith DB, Penn CE, Ward DB, Tritt D. Intimate partner physical abuse perpetration and victimization risk factors: A meta-analytic review. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2003;10:65–98. [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA. Measuring intrafamily conflict and violence: The Conflict Tactics (CT) Scale. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1979;41:75–88. [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA. Future research on gender symmetry in physical assaults on partners. Violence Against Women. 2006;12:1086–1097. doi: 10.1177/1077801206293335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stubbs J, Crosby L, Forgatch M, Capaldi DM. Family and Peer Process Code: Training manual: A synthesis of three OSLC behavior codes. Oregon Social Learning Center; Eugene: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Vivian D, Malone J. Relationship factors and depressive symptomatology associated with mild and severe husband-to-wife physical aggression. Violence and Victims. 1997;12:3–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welsh MC, Pennington BF, Groisser DB. A normative-developmental study of executive function: A window on the prefrontal function in children. Developmental Neuropsychology. 1991;7:131–149. [Google Scholar]

- Whitaker DJ, Haileyesus T, Swahn M, Saltzman LE. Differences in frequency of violence and reported injury between relationships with reciprocal and nonreciprocal intimate partner violence. American Journal of Public Health. 2007;97:941–947. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.079020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White L, Rogers SJ. Economic circumstances and family outcomes: A review of the 1990s. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 2000;62:1035–1051. [Google Scholar]

- Winstok Z. Toward an interactional perspective on intimate partner violence. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2007;12:348–363. [Google Scholar]

- Woodward LJ, Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ. Romantic relationships of young people with childhood and adolescent onset antisocial behavior problems. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2002;30:231–243. doi: 10.1023/a:1015150728887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

ACTIONS

- View on publisher site

- PDF (439.3 KB)

- Cite

- Collections

- Permalink

RESOURCES

Similar articles

Cited by other articles

Links to NCBI Databases

On this page

- Abstract

- Persistence and Desistance of Physical Aggression by Men

- Psychological Aggression

- A Dynamic Developmental Systems Perspective and Both Partners’ Risk Characteristics

- The Present Study

- Method

- Results

- Discussion

- Acknowledgments

- References

Follow NCBI

NCBI on X (formerly known as Twitter)NCBI on FacebookNCBI on LinkedInNCBI on GitHubNCBI RSS feed

Connect with NLM

NLM on X (formerly known as Twitter)NLM on FacebookNLM on YouTube

National Library of Medicine

8600 Rockville Pike

Bethesda, MD 20894