MORGAN FREEMAN

Main menu

Personal tools

Contents

hide

- (Top)

- Early life and education

- CareerToggle Career subsection

- Other venturesToggle Other ventures subsection

- Personal life

- Artistry and legacy

- Filmography and theater credits

- Awards and nominations

- See also

- References

- External links

Morgan Freeman

106 languages

Tools

Appearancehide

Text

- SmallStandardLarge

Width

- StandardWide

Color (beta)

- AutomaticLightDark

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

For the director, see Morgan J. Freeman.

| Morgan Freeman | |

|---|---|

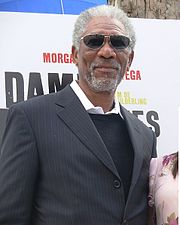

| Freeman in 2023 | |

| Born | June 1, 1937 (age 87) Memphis, Tennessee, U.S. |

| Occupations | Actorproducernarrator |

| Years active | 1964–present |

| Organization | Revelations Entertainment |

| Works | Full list |

| Spouses | Jeanette Adair Bradshaw(m. 1967; div. 1979)Myrna Colley-Lee(m. 1984; div. 2010) |

| Children | 4 |

| Awards | Full list |

| Military career | |

| Service/branch | United States Air Force |

| Years of service | 1955-1959 |

| Rank | Airman first class |

| Duration: 32 seconds.0:32Morgan Freeman’s voice from BBC Radio 4’s The Film Programme, September 12, 2008.[1] | |

Morgan Freeman[2] (born June 1, 1937) is an American actor, producer, and narrator. Throughout a career spanning five decades, he has received numerous accolades, including an Academy Award, a Golden Globe Award, and a Screen Actors Guild Award as well as a nomination for a Tony Award. He was honored with the Kennedy Center Honor in 2008, an AFI Life Achievement Award in 2011, the Cecil B. DeMille Award in 2012, and Screen Actors Guild Life Achievement Award in 2018. He is widely regarded as one of the greatest actors of all time.[3][4]

Born in Memphis, Tennessee, Freeman was raised in Mississippi, where he began acting in school plays. He studied theater arts in Los Angeles and appeared in stage productions in his early career. He rose to fame in the 1970s for his role in the children’s television series The Electric Company. Freeman then appeared in the Shakespearean plays Coriolanus and Julius Caesar, the former of which earned him an Obie Award. In 1978, he was nominated for the Tony Award for Best Featured Actor in a Play for his role as Zeke in the Richard Wesley play The Mighty Gents.

Freeman received the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor for his role as a former boxer in Clint Eastwood‘s sports drama Million Dollar Baby (2004). He was Oscar-nominated for Street Smart (1987), Driving Miss Daisy (1989), The Shawshank Redemption (1994), and Invictus (2009). Other notable roles include in Glory (1989), Lean on Me (1989), Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves (1991), Unforgiven (1992), Se7en (1995), Amistad (1997), Gone Baby Gone (2007), and The Bucket List (2007). He also portrayed Lucius Fox in Christopher Nolan‘s The Dark Knight Trilogy (2005–2012) and starred in the action films Wanted (2008), Red (2010), Oblivion (2013), Now You See Me (2013), and Lucy (2014).

Known for his distinctive voice, he has narrated numerous documentary projects including The Long Way Home (1997), March of the Penguins (2005), Through the Wormhole (2010–2017), The Story of God with Morgan Freeman (2016–2019), Our Universe (2022) and Life on Our Planet (2023). He made his directorial debut with the drama Bopha! (1993). He founded film production company Revelations Entertainment with business partner Lori McCreary in 1996 where he produced numerous projects including CBS political drama Madam Secretary from 2014 to 2019.

Early life and education

Freeman was born on June 1, 1937 in Memphis, Tennessee.[5] He is the son of Mamie Edna (née Revere; 1912–2000), a teacher,[6] and Morgan Porterfield Freeman (July 6, 1915 – April 27, 1961),[2] a barber, who died of cirrhosis in 1961.[7] He has three older siblings.[8] Some of Morgan’s great-great-grandparents were enslaved people who migrated from North Carolina to Mississippi. He later discovered that his white maternal great-great-grandfather had lived with and was buried beside Freeman’s black great-great-grandmother in the segregated South, as the two could not legally marry at the time.[6] The DNA test suggested that among all of his African ancestors, a little over one-quarter came from the area that stretches from present-day Senegal to Liberia and three-quarters came from the Congo–Angola region.[9]

As an infant, Freeman was sent to his paternal grandmother in Charleston, Mississippi.[10][11] He moved frequently during his childhood, living in Greenwood, Mississippi; Gary, Indiana; and finally Chicago.[11] He made his acting debut at age nine, playing the lead role in a school play. He then attended Broad Street High School, a building which serves today as Threadgill Elementary School in Greenwood.[12] At age 12, he won a statewide drama competition, and while settling into school, discovered music and theater. When Freeman was 16 years old, he contracted pneumonia.[13]

Freeman graduated high school in 1955, but turned down a partial drama scholarship from Jackson State University, opting instead to enlist in the United States Air Force.[7] He served as an Automatic Tracking Radar repairman, rising to the rank of airman first class.[14] After serving from 1955 to 1959, he moved to Los Angeles and took acting classes at the Pasadena Playhouse.[7] He also studied theater arts at Los Angeles City College, where a teacher encouraged him to embark on a dance career.[15]

Career

1964–1988: Early work and rise to prominence

Freeman worked as a dancer at the 1964 World’s Fair and was a member of the Opera Ring musical theater group in San Francisco.[16] He acted in a touring company version of The Royal Hunt of the Sun, and also appeared as an extra in Sidney Lumet‘s 1965 drama film The Pawnbroker starring Rod Steiger.[16] Between acting and dancing jobs, Freeman realized that acting was where his heart lay. “After [The Royal Hunt of the Sun], my acting career just took off,” he later recalled.[16] Freeman made his Off-Broadway debut in 1967, opposite Viveca Lindfors in The Niggerlovers, a show about the Freedom Riders during the American Civil Rights Movement,[17] before debuting on Broadway in 1968’s all-black version of Hello, Dolly! that also starred Pearl Bailey and Cab Calloway.[18] In 1969, Freeman also performed on stage in The Dozens.[19]

Beginning in 1971, Freeman starred in the PBS children’s television show The Electric Company, which gave him financial stability and recognition among American audiences.[11] His work on the show was tiring, so he quit in 1975.[15] Television producer Joan Ganz Cooney said that Freeman loathed appearing in The Electric Company, saying “it was a very unhappy period in his life”.[20] Freeman later acknowledged that he does not think about the show, but he was grateful to have been a part of it.[21] His first credited appearance in a feature film was in 1971’s Who Says I Can’t Ride a Rainbow!, a family drama starring Jack Klugman.[19] Also that year, Freeman performed in a theater production of Purlie.[22] After a short career break, he returned to work in 1978, appearing in two stage productions: 1978’s The Mighty Gents, winning a Drama Desk Award and a Clarence Derwent Award for his role as a wino,[23] and White Pelicans.[24] Freeman continued to work in theater and a year later, appeared in the Shakespearean tragedies Coriolanus, receiving the Obie Award in 1980 for the title role[16] as well as Julius Caesar.[25]

In 1980, he had a small role as Walter in the drama Brubaker, which starred Robert Redford as a prison warden.[26] Freeman next appeared in the television film, Attica (1980), which is about the 1971 Attica Prison riot and its aftermath.[27] A year later he had a lead role in Peter Yates‘ Eyewitness with co-stars William Hurt and Sigourney Weaver.[28] From 1982 to 1984, Freeman was a cast member of the soap opera Another World, playing architect Roy Bingham.[29] After several small roles in dramas, he starred in Marie (1985), a film adaptation of Marie: A True Story by Peter Maas; he portrayed Charles Traughber.[30] He also appeared in the miniseries The Atlanta Child Murders.[31] Freeman also had a small role in the drama That Was Then… This Is Now, based on the novel of the same name by S. E. Hinton.[32] In the mid-1980s, he began accepting prominent supporting roles in feature films, earning him a reputation for depicting wise, fatherly characters.[11]

In addition to television films, in 1987, Freeman played a violent street hustler, a role that diverged from his previous roles, in Street Smart co-starring Christopher Reeve and Kathy Baker. Freeman’s performance was praised by film critics, including Roger Ebert who wrote: “Freeman has the flashier role, as a smart, very tough man who can be charming or intimidating-whatever’s needed… Freeman creates such an unforgettable villain.”[33] Freeman’s performance earned him an Academy Award nomination for Best Supporting Actor.[34] He later said that he considered Street Smart to be his breakthrough role.[21] In his next film, he played Craig in the drama Clean and Sober with co-stars Michael Keaton and Kathy Baker. Although the film was not a box-office hit, it gained fair reviews; Roger Ebert gave the film 41⁄2 out of 5 stars and called the performances “superb”.[35] Freeman also received Obie Awards for his roles as a preacher in the musical The Gospel at Colonus, and as Hoke Colburn in the play Driving Miss Daisy, respectively.[16]

1989–1996: Hollywood breakthrough

Freeman had four film releases in 1989. In the first, he starred as Sergeant Major John Rawlins in Glory, directed by Edward Zwick, about the 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment, the Union Army‘s second African-American regiment in the American Civil War. Writing for The Washington Post, Desson Thomson praised Freeman and co-star Denzel Washington for their “warming sense of fraternity”.[36] Glory was nominated for five Academy Awards and won three: Best Supporting Actor for Washington, Best Cinematography, and Best Sound.[37] Next, Freeman starred in the comedy-drama Driving Miss Daisy, alongside Jessica Tandy and Dan Aykroyd. Based on Alfred Uhry‘s play of the same name in which Freeman had appeared previously, he reprises his role of Hoke Colburn, chauffeur for a Jewish widow. The film was a commercial success and grossed US$145 million worldwide.[38] Film critics were mainly positive; Henry Sheehan from The Hollywood Reporter opined that Freeman and Tandy’s performances complemented each other while retaining their “individual star-quality”.[39] The film was nominated for nine Academy Awards (and received four, Best Picture being one of them), including Best Actor for Freeman.[37]

His third release was the biographical drama Lean on Me, in which he portrays the principal of an under-performing and drug- and crime-ridden New Jersey high school. Jane Galbraith of Variety magazine thought Freeman’s casting was “wonderful”.[40] Lastly in 1989, he starred in Walter Hill‘s Johnny Handsome, a crime drama in which he plays a New Orleans police officer.[41] In a 1990 interview, Freeman said that Glory was one of his favorite releases—”The Black legacy is as noble, is as heroic, is as filled with adventure and conquest and discovery as anybody else’s. It’s just that nobody knows it.”[15] In 1990, Freeman provided the voice of Frederick Douglass in The Civil War, a television miniseries about the American Civil War.[42] In the same year he starred in the critically panned The Bonfire of the Vanities. According to the review aggregate site Rotten Tomatoes, the film has an approval rating of 16% based on 51 reviews.[43] In the summer of 1990, he played Petruchio, a role he had been thinking about for six years, in Shakespeare’s The Taming of the Shrew, which opened at Delacorte theater in New York City. “[Petruchio] seems to have a lot of fun in life,” he said.[44] In 1991, Freeman had a supporting role in Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves, an action-adventure starring Kevin Costner. The film was a commercial success,[45] but garnered mixed reviews from critics; The New York Times‘ Vincent Canby thought Freeman played Azeem with “wit and humor” despite the “muddled” plot.[46]

Freeman also narrated The True Story of Glory Continues, a documentary about the 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment.[47] In 1992, he appeared in Clint Eastwood‘s western Unforgiven, which won four Academy Awards including Best Picture.[48] The film depicts William Munny (Eastwood), an aging outlaw and killer who takes on one more job with old friend Ned Logan (Freeman). Unforgiven was widely acclaimed, with one critic calling Freeman’s performance “outstanding”.[49] Also in 1992 Freeman starred in the John G. Avildsen directed drama The Power of One acting opposite Stephen Dorf and John Gielgud in a loose adaptation of Bryce Courtenay‘s 1989 novel of the same name, in which he plays boxing coach Geel Piet.[50] In 1993, Freeman made his directorial debut with the drama Bopha!, which tells the story of a black policeman (Danny Glover) during South Africa’s apartheid era. Bopha! was well-received, in particular for Freeman’s directing. Hal Hinson of The Washington Post wrote: “Freeman lays out the father-son dynamics with great skill and very little fuss. There’s no hysteria in his approach; instead, he sticks to the facts, relying on his cast to provide the emotion. The result is a surprisingly powerful, insightful film.”[51] Kenneth Turan from Los Angeles Times also complimented Freeman’s direction but thought the film was “more predictable than powerful”.[52]

In 1994, Freeman portrayed Red, the redeemed convict in Frank Darabont‘s acclaimed drama The Shawshank Redemption, with co-star Tim Robbins. It is based on the 1982 Stephen King novella Rita Hayworth and Shawshank Redemption. Freeman was cast at the suggestion of producer Liz Glotzer, despite the novella’s character of a white Irishman.[53] Filming proved to be challenging, mainly because of Darabont’s need for multiple takes. Freeman said, “The answer [I’d give him] was no… having to do something again and again for no discernible reason tends to be a bit debilitating to the energy.”[53] Nevertheless, his performance was described as “quietly impressive” and “moving” by The New York Times.[54] At the 67th Academy Awards the film received Academy Award nominations for Best Picture and a nomination for Freeman for Best Actor losing to Tom Hanks in Forrest Gump (1994).[55] Since its release, The Shawshank Redemption has remained popular among audiences.[53] In 1994, Freeman served as a member of the jury at the 44th Berlin International Film Festival.[56]

Outbreak (1995), a medical thriller directed by Wolfgang Petersen, was Freeman’s next film. He played General Billy Ford, a doctor dealing with an outbreak of a fictional virus in a small town. The film stars Dustin Hoffman, Rene Russo, and Donald Sutherland. Outbreak was a box-office success, grossing $189.8 million worldwide,[57] but gained a mixed critics’ response.[58] Mick LaSelle of the San Francisco Chronicle credited Freeman for his performance which may have been unappreciated by viewers.[59] In 1995, Freeman starred with Brad Pitt in David Fincher‘s crime thriller Seven, the story of two detectives who attempt to identify a serial killer who bases his murders on the Christian seven deadly sins. Freeman’s performance generated a positive response; Owen Gleiberman of Entertainment Weekly wrote: “Freeman plays nearly every scene in a doleful hush; he makes you lean in to hear his words, to ferret out the hints of anger and regret that haunt this weary knight.”[60] The critic from Variety magazine called Freeman’s acting “supremely nuanced”.[61]

While filming Outbreak, Freeman expressed an interest in starting a film production company. He turned to McCreary, the producer of Bopha!, to be his business partner. Freeman explained that he wanted to achieve representation on screen, explore challenging issues and reveal hidden truths, so they chose to name their firm Revelations Entertainment.[62] A year later, he appeared in Chain Reaction as Paul Shannon, a science-fiction thriller co-starring Keanu Reeves and Rachel Weisz. The film was a critical and commercial disappointment.[63][64] Next, he was cast opposite Robin Wright in 1996’s Moll Flanders, a period drama based on the novel of the same name. The film received a mixed reception; Greg Evans from Variety magazine said Freeman gave a “sweet” performance,[65] while The New York Times critic thought he was miscast.[66]

1997–2004: Critical success and established actor

In 1997, Freeman narrated the Academy Award-winning documentary The Long Way Home, about Jewish refugees’ liberation after World War II and the establishment of Israel.[24] He also appeared in Steven Spielberg‘s historical epic Amistad alongside Djimon Hounsou, Anthony Hopkins, and Matthew McConaughey. Based on the events in 1839 aboard the slave ship La Amistad, the film was mostly well-received and earned four nominations at the Academy Awards.[67][68] The critic from Salon magazine, however, thought the film lacked inspiration and Freeman’s role was “utterly cryptic”.[69] In that same year, he was cast as psychologist Alex Cross in Kiss the Girls, a thriller based on James Patterson‘s 1995 novel of the same name. In a mixed review, Peter Stack of San Francisco Chronicle thought Freeman and co-star Ashley Judd gave strong performances despite the lengthy plot.[70]

Freeman went on to star in Deep Impact (1998), a science-fiction disaster film in which he played President Tim Beck.[71] The story depicts humanity’s attempt to destroy a 7-mile (11 km) wide comet set to collide with Earth and cause a mass extinction. The film was a box-office hit, despite competition from Armageddon, another summer blockbuster of the year.[72] Continuing with the disaster genre, he then starred opposite Christian Slater in 1998’s Hard Rain, centering on a heist and man-made treachery amidst a natural disaster in a small Indiana town. The film was unpopular with critics; Lawrence Van Gelder of The New York Times called the characters “one-dimensional” and the film “routine”.[73] Freeman returned to the screen in 2000 with the lead role of Charlie in the comedy Nurse Betty, featuring Renée Zellweger, Chris Rock, and Greg Kinnear. The film premiered at the Cannes Film Festival to mainly positive reviews; the critic from Variety magazine thought Freeman and Rock had “wonderful chemistry”.[74] Next, he appeared in Under Suspicion (2000), a thriller remake of the 1981 French film Garde à vue. The film had been “carting round” for twelve years before Freeman was able to produce it under Revelations Entertainment.[75] He co-starred with Gene Hackman; “Working with Gene was wonderful. I didn’t find it too hard working with an icon I so respected,” Freeman said.[75] Upon release, Under Suspicion was met with lukewarm reception;[76] CNN‘s Paul Tatara praised the actors but thought the film was “too tawdry to be completely entertaining, and too static to generate much excitement”.[77]

In 2001, Freeman reprised his role of Alex Cross in Along Came a Spider, a sequel to 1997’s Kiss the Girls. The film received mixed-to-negative reviews.[78] Susan Wloszczyna of USA Today observed that “Freeman strides with noble authority” but thought the overall film was unmemorable.[79] In 2002, Freeman was cast opposite Ben Affleck in the spy thriller The Sum of All Fears. It is based on Tom Clancy‘s 1991 novel of the same name, about a plot by an Austrian Neo-Nazi to trigger a nuclear war between the United States and Russia, so that he can establish a fascist superstate in Europe. The Sum of All Fears received moderate reviews,[80] but was a commercial success, grossing $193.9 million worldwide.[81] Next, Freeman starred alongside Ashley Judd and Jim Caviezel in High Crimes (2002), a legal thriller based on Joseph Finder‘s 1998 novel of the same name. The story follows lawyer Claire (Judd), whose husband (Caviezel) is arrested and placed on trial for the murder of villagers while he was in the Marines. Although several critics were unimpressed with the story, they credited Freeman and Judd for their chemistry and performances.[82][83] In 2003, Freeman appeared as God in the hit comedy Bruce Almighty with Jim Carrey and Jennifer Aniston.[84]

Next, he starred in the science fiction horror Dreamcatcher, adapted from Stephen King‘s 2001 novel of the same name. The film was a box-office flop,[85] and garnered mostly negative reviews; Dreamcatcher has an approval rating of 28% on review aggregate site Rotten Tomatoes.[86] Also in 2003, Freeman starred in two other dramas that were not widely seen, Levity and Guilty by Association.[87][88] His 2004 releases were comedy The Big Bounce and sports drama Million Dollar Baby.[89][90] In the latter, directed by Clint Eastwood, Freeman portrayed an elderly former boxer. The film won four Academy Awards, including Best Picture, Best Director, Best Actress (Hilary Swank), and Best Supporting Actor, earning Freeman his first Academy Award.[11] Freeman was also nominated for a Golden Globe Award in the same category.[91] Roger Ebert complimented Freeman’s “flat and factual” narration,[92] and Timeout magazine thought the cast fully inhabited their roles.[93]

2005–2013: Documentaries and thriller films

Freeman made six appearances in various films in 2005. In the drama An Unfinished Life, Freeman plays Mitch, a neighbor of a Wyoming rancher (Robert Redford). The film had a mixed response; The Guardian critic thought it was amiable but questioned the purpose of Freeman’s “sidekick” role.[94] Freeman’s authoritative voice led to his narration of two documentaries; Steven Spielberg’s War of the Worlds and the Academy Award-winning March of the Penguins.[24] He also appeared in Christopher Nolan‘s Batman Begins, the first installment in what would become The Dark Knight Trilogy, as the fictional Lucius Fox.[95] After this, he co-starred with Jet Li in the action-thriller Unleashed, playing Sam, a blind piano tuner who helps Li’s character turn his life around. The film gained a mixed-to-positive reception; Peter Hartlaub of San Francisco Chronicle was confused with the genre and thought Freeman’s character interrupted the narrative.[96] Freeman’s next role was in the thriller Edison, which bombed at the box office.[97] In his last release of 2005, he provided the voice of Neil Armstrong in the documentary Magnificent Desolation: Walking on the Moon 3D.[98]

Freeman starred in 2006’s The Contract, as assassin Frank Carden opposite John Cusack. The film was released direct-to-video, which critic John Cornelius suggests was unsurprising, considering the generic formula of the thriller.[99] Freeman next appeared in Lucky Number Slevin (2006), a crime thriller directed by Paul McGuigan. Starring a principal cast of Josh Hartnett, Bruce Willis, Lucy Liu, Stanley Tucci, and Ben Kingsley, the film garnered mixed reception.[100] David Mattin of BBC wrote: “Kingsley and Freeman shine individually, but their inevitable, climactic clash of heads lacks force. Like its leading man [Hartnett], this movie presents a charming façade with nothing much underneath.”[101] Next, Freeman portrayed himself in the low-budget comedy 10 Items or Less opposite Paz Vega.[102] Two weeks after its theatrical release, 10 Items or Less was made available for download from ClickStar, a film distribution company that Freeman co-founded that year.[103]

In 2007, Freeman reprised his role as God in Evan Almighty, a sequel to 2003’s Bruce Almighty, with Steve Carell. Evan Almighty was a box-office failure[104] and negatively received;[105] The Guardian critic wrote: “A cast full of people who have been frequently funny elsewhere flounder in this deluge of sentimentality and CGI. Avoid like the Ten Plagues.”[106] The drama Feast of Love was Freeman’s second release of 2007. It is based on the 2000 novel The Feast of Love by Charles Baxter, about a group of friends living in suburban Oregon who come into contact with a free spirit who changes their outlook on life; Peter Bradshaw of The Guardian sarcastically remarked that it was great to see Freeman in a challenging role.[107] Freeman had a supporting part in Gone Baby Gone (2007), a mystery thriller that was also Ben Affleck’s directorial debut. Adapted from the 1998 novel of the same name by Dennis Lehane, Freeman plays Captain Jack Doyle of the Boston Police Department. The story and cast performances were positively received; Time Out magazine called it “flawed but impressive”.[108] Afterward, he starred in Rob Reiner‘s 2007 comedy The Bucket List opposite Jack Nicholson.[109] The plot follows two terminally ill men on a road trip with a list of things to do before they die. The film grossed $175 million worldwide.[110]

In 2008, Freeman was cast in the action-thriller Wanted, a loose adaptation of the comic book miniseries by Mark Millar and J. G. Jones. The plot revolves around Wesley Gibson (James McAvoy), a frustrated account manager who discovers that he is the son of a professional assassin and decides to join the Fraternity, a secret society of which Sloan (Freeman) is the leader. Principal photography took place in Chicago; co-star rapper Common remarked on the set atmosphere: “Freeman is a cool guy. He’d be walking around joking and singing and just dancing. You know, artists are free and I just felt the freedom in him.”[111] The film received generally favorable reviews; Peter Howell of Toronto Star thought it was original and one of Freeman’s bolder performances to date.[112] Freeman narrated The Love Guru (2008),[113] before appearing in The Dark Knight (2008), the second installment of Christopher Nolan’s Dark Knight Trilogy, in which he reprised his role as Lucius Fox.[114] Freeman returned to Broadway in 2008 after an eighteen-year absence to co-star with Frances McDormand and Peter Gallagher in Clifford Odets‘ play, The Country Girl, directed by Mike Nichols.[115]

Freeman continued to accept roles in a diverse range of genres. In 2009, Freeman starred opposite Antonio Banderas in the heist movie Thick as Thieves.[116] Next, he collaborated with Christopher Walken and William H. Macy for the comedy The Maiden Heist. For some time, Freeman expressed a desire to do a film based on Nelson Mandela. Initially, he wanted to adapt Mandela’s autobiography Long Walk to Freedom into a screenplay, but plans were never finalized.[117] Instead, he purchased the film rights to John Carlin’s book: Playing the Enemy: Nelson Mandela and the Game That Made a Nation.[118] The book was adapted into a film which Clint Eastwood directed, Invictus, starring Freeman as Mandela and Matt Damon as rugby team captain Francois Pienaar.[119] The biographical drama received positive reviews for Freeman’s performance; Roger Ebert wrote: “Freeman does a splendid job of evoking the man Nelson Mandela … He shows him as genial, confident, calming, over what was clearly a core of tempered steel.”[120] Freeman received Best Actor nominations at the Academy Awards and Golden Globes, as well as a nomination for Outstanding Performance by a Male Actor at the Screen Actors Guild Awards.[121][122][123] The same year he provided the narration for Janet Langhart‘s Anne and Emmett, a play featuring an imaginary conversation between Emmett Till and Anne Frank, both killed as young teenagers because of racial persecution.[124]

Freeman’s sole film release of 2010 was Red with co-stars Bruce Willis, Helen Mirren, and John Malkovich.[125] Red is loosely adapted from the comic-book series Red, created by Warren Ellis and Cully Hamner and published by the DC Comics imprint Homage. Freeman plays CIA mentor Joe, who helps retired fellow agent Frank (Willis) to uncover some assassins. The film was a critical and commercial success;[126] writing for Melbourne’s The Age, Jim Schembri praised Freeman and the cast who “bring an infectious comic energy to their roles”.[127]

Besides film, Freeman worked on other projects. In January 2010, he replaced Walter Cronkite as the voiceover introduction to the CBS Evening News presented by Katie Couric.[128] CBS gave the need for consistency in introductions for regular news broadcasts and special reports as the basis for the change.[128] Deborah Myers, head of Science Channel, approached Freeman to be the presenter of Through the Wormhole (2010–17). She had heard that he was “really interested in space and the universe,” and the pair agreed to develop the series together.[129]

In 2011, Freeman narrated the fantasy Conan the Barbarian and appeared in the family drama Dolphin Tale, as prosthetic specialist Dr. McCarthy.[130] Returning to theater in 2011, Freeman was featured with John Lithgow in the Broadway debut of Dustin Lance Black‘s play, 8, a staged reenactment of Perry v. Brown, the federal trial that overturned California’s Proposition 8 ban on same-sex marriage. Freeman played Attorney David Boies.[131] The production was held at the Eugene O’Neill Theatre in New York City to raise money for the American Foundation for Equal Rights.[132][133] Freeman had a lead role in the 2012 drama The Magic of Belle Isle, as an alcoholic novelist trying to write again. The film fared poorly with critics, gaining only a 29% approval rating on Rotten Tomatoes.[134] Lastly in 2012, Freeman reprised his role as Lucius Fox for the third time in The Dark Knight Rises.[135]

A number of box office hits were released in 2013. Freeman appeared in the action-thriller Olympus Has Fallen, the first installment in what would become the Has Fallen film series;[136] he portrays Speaker of the House Allan Trumbull. The San Francisco Chronicle critic gave Olympus Has Fallen 3 out of 4 stars and opined that Freeman gave an amicable supporting performance.[137] He then starred in the science fiction drama Oblivion, with co-star Tom Cruise, as veteran soldier Malcolm Beech,[138] and appeared in the thriller Now You See Me, as an ex-magician.[139] Lastly, he played a retiree in Last Vegas, with co-stars Michael Douglas, Robert De Niro, Kevin Kline, and Mary Steenburgen.[140] Filmed in Las Vegas and Atlanta,[141] Last Vegas was praised for its cast’s chemistry, and one critic thought Freeman brought the most amusement.[142]

2014–present: Continued success

In 2014, Freeman voiced the character Vitruvius in The Lego Movie, a commercially successful 3D animation.[143] He starred in Transcendence, a science fiction thriller directed by Wally Pfister in his directorial debut, in which Freeman plays scientist Joseph Tagger. Critic reviews of the film were generally mixed, according to Metacritic.[144] Next, he co-starred in the action Lucy (2014), about a woman (Scarlett Johansson) who gains psychokinetic abilities when a nootropic drug is absorbed into her bloodstream. Freeman plays Professor Samuel Norman, who helps her research the condition. Producer Virginie Silla wanted Freeman for the part because of his experience in portraying a character of wisdom.[145] “He was the perfect actor,” she said.[145] Upon the release of Lucy, critical reception ranged from mixed-to-positive.[146] In the same year Freeman appeared in Dolphin Tale 2, the sequel to 2011’s Dolphin Tale,[147] and 5 Flights Up, a comedy-drama.[148] At the end of 2014, Freeman appeared as himself, among other celebrities, in the documentary Lennon or McCartney.[149]

Kazuaki Kiriya‘s action-thriller Last Knights was Freeman’s first film of 2015, starring opposite Clive Owen. The plot centers on a band of warriors who seek to avenge the loss of their master at the hands of a corrupt minister. Reviews were largely underwhelming;[150] Sara Stewart of New York Post called it “bloody bad”, adding: “Once-proud box office names are its first casualties.”[151] Freeman next joined the cast of Ted 2, a comedy sequel to Ted, directed by Seth MacFarlane. The story follows the talking teddy bear Ted as he fights for civil rights in order to be recognized as a person. Freeman portrays Patrick Meighan, a highly respected civil rights attorney.[152] A television series, Madam Secretary, also occupied Freeman’s time. He played Chief Justice Frawley of the United States Supreme Court in a recurring role in the series. He and his producing partner Lori McCreary were executive producers.[153] Freeman directed the first episode; McCreary remarked of his directing style, “What’s riveting is that he can achieve a complete tonal change in performance with the least amount of direction… Everybody behaves better when Morgan is there… but he’s very fun.”[154] At the end of 2015, Freeman played a U.S. senator in the thriller Momentum.[155]

Reprising his role as Allan Trumbull, Freeman appeared in London Has Fallen, the 2016 sequel to Olympus Has Fallen. The film follows a plot to assassinate the world leaders of the G7 as they attend the British Prime Minister‘s funeral in London, as well as Secret Service agent Mike Banning’s efforts to protect U.S. President Benjamin Asher (Aaron Eckhart) from being killed. The film was a commercial success,[156] however, writing for A.V. Club, Ignatiy Vishnevetsky criticized the cheap filmmaking saying, “The movie periodically cuts to overqualified supporting actors—including Freeman, Melissa Leo, and Robert Forster… (it’s possible to write something that will sound like garbage even when spoken in Freeman’s sonorous voice.)”[157] Next, Freeman reprised his role as Thaddeus Bradley, starring in Now You See Me 2 (2016),[158] the sequel to Now You See Me, the sequel grossing a successful $334.9 million worldwide.[159] Finally, he had a leading role in the historical drama Ben-Hur, the fifth film adaptation of the 1880 novel Ben-Hur: A Tale of the Christ by Lew Wallace. Freeman expressed interest in playing Sheik Ilderim, a wealthy Nubian sheik, stating: “This character has quite a bit of power in the story. And I like playing power. It’s something about my own personal ego.”[160] Ben-Hur turned out to be one of 2016’s biggest box-office bombs.[161][162]

In 2017, Freeman appeared in two comedies: Going in Style and Just Getting Started. The first one is a remake of the 1979 film with the same name, co-starring Michael Caine and Alan Arkin; in it they play bank robbers after their pensions are canceled.[163] It opened to a mixed response;[164] The Telegraph‘s Robbie Collin thought the trio of actors looked tired before the end of it.[165] Just Getting Started, in which Freeman starred with Tommy Lee Jones and Rene Russo, was critically panned by reviewers.[166] The plot follows an ex-FBI agent (Jones) who must put aside his personal feud with a former mob lawyer (Freeman) at a retirement home when the mafia comes to kill the pair. Freeman also hosted the National Geographic The Story of God with Morgan Freeman and The Story of Us with Morgan Freeman, in 2016 and 2017, respectively.[167]

In 2018, Freeman narrated Alpha, a historical drama set in the last ice age. He then starred in Disney’s The Nutcracker and the Four Realms, a retelling of E. T. A. Hoffmann‘s short story “The Nutcracker and the Mouse King” and Marius Petipa‘s and Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky‘s ballet The Nutcracker.[168] Finally he had an uncredited role as Jerome in the biographical drama Brian Banks, a high-school football player who was falsely accused of rape and upon his release attempted to fulfill his dream of making the NFL.[169] In 2019, Freeman starred opposite John Travolta in The Poison Rose, an adaptation of the novel by Richard Salvatore.[170] In Angel Has Fallen, Freeman reprised his role as Allan Trumbull, the third installment in the Has Fallen film series, following Olympus Has Fallen and London Has Fallen. Although critical reception was mixed,[171] the film was a box office success, earning $147.5 million worldwide.[172]

Freeman next appeared alongside an ensemble cast in George Gallo‘s crime comedy The Comeback Trail (2020) and in Coming 2 America (2021), a sequel to the 1988 film.[173] On November 20, 2022, Freeman performed with Ghanim Al-Muftah at the opening ceremony of the 2022 FIFA World Cup in Qatar.[174][175]

Other ventures

Environmental activism

In 2004, Freeman helped form the Grenada Relief Fund to aid people affected by Hurricane Ivan on the island of Grenada. The fund has since become PLANIT NOW, an organization that seeks to provide preparedness resources for people living in areas affected by hurricanes and severe storms.[176] In 2014, he narrated a clip titled What’s Possible which had its debut at the United Nations climate summit.[177] Freeman has donated to the Mississippi Horse Park in Starkville, Mississippi, part of Mississippi State University and Freeman has several horses that he takes there.[178]

After learning about the decline of honeybees, Freeman decided to turn his 124-acre ranch into a bee sanctuary in July 2014 beginning with 26 beehives.[179]

Political activism

In 2005, Freeman criticized the celebration of Black History Month, saying: “I don’t want a black history month. Black history is American history.”[180] He opined that the only way to end racism is to stop talking about it, and he noted that there is no “white history month”.[180] In an interview with 60 Minutes‘s Mike Wallace, Freeman said: “I am going to stop calling you a white man and I’m going to ask you to stop calling me a black man.”[180][181] Freeman supported the defeated proposal to change the Mississippi state flag, which incorporated the Confederate battle flag at the time.[182][183] In an interview on CNN’s Piers Morgan Tonight, Freeman drew controversy when he accused the Tea Party movement of racism.[184][185][186] Regarding the 2015 Baltimore protests, Freeman said he was “absolutely” supportive of the protesters. “That unrest [in Baltimore] has nothing to do with terrorism at all, except the terrorism we suffer from the police… Because of the technology—everybody has a smartphone—now in reaction to the death of Freddie Gray we can see what the police are doing. We can show the world, ‘Look, this is what happened in that situation.’ So why are so many people dying in police custody? And why are they all Black? And why are all the police killing them white? What is that? The police have always said, ‘I feared for my safety.’ Well, now we know. OK. You feared for your safety while a guy was running away from you, right?”[187]

During the 2008 presidential election, Freeman endorsed Barack Obama‘s presidential bid, although he said he would not join Obama’s campaign.[188] He provided the voice of the narrator for Disney World‘s The Hall of Presidents when Obama was added to the exhibit,[189][190] and when The Hall of Presidents re-opened on July 4, 2009, at Walt Disney World Resort in Orlando, Florida.[190] On day four of the 2016 Democratic National Convention, Freeman provided the voiceover for the video introduction of Democratic presidential candidate Hillary Clinton.[191][192] On September 19, 2017, Freeman appeared in a video by the Committee to Investigate Russia group,[193][194] in which he declared “we [United States] are at war” and accusing Russia of “launching cyber attacks and spreading false information”.[195][196]

In June 2021 he and Linda Keena, a professor at University of Mississippi donated $1 million to the university establishing the Center for Evidence-Based Policing and Reform.[197]

Business ventures

In 1997, Freeman and business partner Lori McCreary founded Revelations Entertainment, a film production company. They also founded ClickStar in 2006, a film download company, with investment from Intel Corporation.[198] ClickStar ceased operations in 2008.[199] Freeman owns and operates Ground Zero, a blues club in Clarksdale, Mississippi; he is the former co-owner of Madidi, a fine dining restaurant in the same city.[200]

Personal life

Freeman was married to Jeanette Adair Bradshaw from October 22, 1967, until November 18, 1979;[201] he married Myrna Colley-Lee on June 16, 1984.[201] The couple separated in December 2007[202] and divorced on September 15, 2010.[202] Freeman has four children: Alfonso, Deena, Morgana, and Saifoulaye.[203] Freeman and Colley-Lee also raised Freeman’s step-granddaughter from his first marriage, E’dena Hines.[204] On August 16, 2015, 33-year-old Hines was murdered in New York City.[205]

Freeman resides in Charleston, Mississippi and maintains a home in New York City.[206][207] He earned a private pilot’s license at age 65[208] and owns or has owned at least three private aircraft, including both a Cessna Citation 501 and Cessna 414 as well as an Emivest SJ30.[209][210][211]

When asked if he believed in God, Freeman said: “It’s a hard question because as I said at the start, I think we invented God. So if I believe in God, and I do, it’s because I think I’m God.”[212] He later said that his experience working on The Story of God with Morgan Freeman did not change his views on religion.[213] In 2019, it was reported that Freeman found religion in Zoroastrianism.[214]

On the evening of August 3, 2008, Freeman was injured in an automobile crash when his 1997 Nissan Maxima was involved in a rollover near Ruleville, Mississippi. He and his passenger, Demaris Meyer, had to be cut free from the vehicle with hydraulic tools. Freeman was conscious after the crash and joked with a photographer at the scene.[215] He was taken via helicopter to The Regional Medical Center (The Med) hospital in Memphis.[216][217] His left shoulder, arm, and elbow had been broken in the accident, and he received surgery on August 5. Doctors operated on him for four hours to repair nerve damage in his shoulder and arm.[218] His publicist announced he was expected to make a full recovery.[219] Although alcohol was not considered a factor in the crash,[220] Meyer sued Freeman for negligence, claiming that he had been consuming alcohol, but the suit was eventually settled for an undisclosed amount.[221] Since the incident, Freeman suffers from fibromyalgia,[222] for which he wears a compression glove that supports blood circulation.[223]

In December 2010, Freeman joined former President Bill Clinton, President of the United States Soccer Federation Sunil Gulati, and soccer player Landon Donovan in Zurich for a presentation to bid for the U.S. hosting rights for the 2022 FIFA World Cup.[224]

Freeman’s favorite film that he did not work on is Moulin Rouge!.[225] He later reaffirmed this during his tribute speech at Nicole Kidman‘s AFI Life Achievement Award ceremony.[226]

On May 24, 2018, CNN published an investigation in which eight women accused Freeman of “what some called harassment and others called inappropriate behavior” towards them while on the set of films or at his production company, describing an “alleged fixation with how women dressed” and “alleged pattern of looking women up and down while making sexually suggestive comments to them.” An additional eight people claimed to have witnessed Freeman’s alleged conduct, and two of the purported victims accused Freeman of inappropriately touching them, including attempting to lift up a skirt.[227] In response Freeman made a statement: “Anyone who knows me or has worked with me knows I am not someone who would intentionally offend or knowingly make anyone feel uneasy. I apologize to anyone who felt uncomfortable or disrespected—that was never my intent.”[228][229] Lori McCreary’s (his business partner) spokesperson did not respond to CNN’s request for comment.[230] One of the women named as an accuser, Tyra Martin, spoke out against her portrayal in CNN’s report, saying, “I’m not, never was [a victim]. CNN totally misrepresented the video and took my remarks out of context.” Per Essence, Martin “saw many of his comments, though inappropriate, to be said in jest.”[231] Freeman’s lawyer demanded CNN retract the story and submitted a letter disputing the report’s credibility, which CNN rejected as “unfounded”[232] and said declined to address “many of the very specific allegations” made against Freeman;[233] CNN responded: “Is it your position that these women and witnesses are lying? To the contrary, we must assume that Mr. Freeman’s apology is an acknowledgement that he said and did much if not all of what CNN reported, and that his behavior was unacceptable, or else what was he apologizing for?”[233] After a period of deliberation, the Screen Actors Guild (SAG) decided not to take any action against Freeman.[234] In October 2019 Variety reported that, “Since the CNN story broke, the Oscar-winning Freeman has continued to work, but his public persona has taken a hit.”[235]

Artistry and legacy

Freeman’s deep voice is considered to be distinctive, iconic, and recognizable which frequently makes him a preferable choice for narration in films and documentaries.[236][237] The journalist Radhika Sanghani writes that his “deeply reassuring voice, with its mellifluous tones and authoritative presence, is why an entire generation still hear his trademark tones when they think of the almighty”.[238] Freeman said that his voice developed in this way while taking speech classes in college; he found that most people speak in a voice either too fast or too high and he developed a commanding voice by speaking in a lower octave and enunciating each word.[239]

According to author Miriam DeCosta-Willis, Freeman is an intuitive actor. He likes to select his roles carefully, and study the character to ensure he portrays them with depth, sensitivity, and substance.[240] Commenting on Freeman’s persona, Beverly Todd, who co-starred with him in Lean on Me (1989) and The Bucket List (2007) said: “The world knows he is such a consummate actor. He’s a very sharing actor and such a nice guy. He’s not the kind of actor who demands that he has all of the scenes and all the dialogues and all the emphasis is on him”.[241] Freeman has said he is interested in playing character roles[16] and values the importance of listening carefully while filming scenes: “The big danger in acting is to wait for your line. That’s what I never do. I always listen, no matter how many times we do it.”[242]

On October 28, 2006, Freeman was honored at the first Mississippi’s Best Awards in Jackson, Mississippi with the Lifetime Achievement Award for his work in film and theater. He received an honorary Doctor of Arts and Letters degree from Delta State University during the school’s commencement exercises on May 13, 2006.[243] In 2013, Boston University presented him with an honorary Doctor of Humane Letters degree.[244] On November 12, 2014, he was bestowed the honor of Freedom of the City by the City of London.[245]

In 2008, Freeman was chosen as a Kennedy Center Honoree at the John F. Kennedy Center in Washington D.C.[246] In 2011, he received the AFI Life Achievement Award in recognition of his contribution to the film industry. Those who honored Freeman included Sidney Poitier, Samuel L. Jackson, Forest Whitaker, Rita Moreno, Helen Mirren, Clint Eastwood, Cuba Gooding Jr., and Matthew Broderick.[247] In 2012, he was awarded the Golden Globe Cecil B. DeMille Award, which recognizes lifetime achievement in the film industry.[248][249] In August 2017, he was named the 54th recipient of the Screen Actors Guild Life Achievement Award for career achievement and humanitarian accomplishment.[250] His co-star Rita Moreno from The Electric Company presented him the award in the following January.[251]

Filmography and theater credits

Main article: Morgan Freeman on screen and stage

Key filmography

Prolific in film since 1964, Freeman is known for his roles in genres ranging from dramas, historical epics, thrillers, action adventure, science fiction, and comedies. His most acclaimed and highest-grossing films, according to the online portal Box Office Mojo and the review aggregate site Rotten Tomatoes, include:[252][253]

- Street Smart (1987)

- Clean and Sober (1988)

- Glory (1989)

- Driving Miss Daisy (1989)

- Lean on Me (1989)

- Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves (1991)

- Unforgiven (1992)

- The Shawshank Redemption (1994)

- Outbreak (1995)

- Seven (1995)

- Amistad (1997)

- Nurse Betty (2000)

- Along Came a Spider (2001)

- Bruce Almighty (2003)

- Million Dollar Baby (2004)

- Batman Begins (2005)

- Gone Baby Gone (2007)

- The Bucket List (2007)

- Wanted (2008)

- The Dark Knight (2008)

- Invictus (2009)

- RED (2010)

- The Dark Knight Rises (2012)

- Oblivion (2013)

- Now You See Me (2013)

- Last Vegas (2013)

- The Lego Movie (2014)

- Lucy (2014)

- Now You See Me 2 (2016)

Select theater roles[254]

- The Niggerlovers (1967)

- Purlie (1970–71)

- Coriolanus (1979)

- Julius Caesar (1979)

- Driving Miss Daisy (1987–1990)

- The Gospel at Colonus (1988)

- The Taming of the Shrew (1990)

Select television roles[253]

- The Electric Company (1971–1977)

- The Long Way Home (1997)

- The Story of God with Morgan Freeman (2016)

- The Story of Us with Morgan Freeman (2017)

- Madam Secretary (2017)

- The Kominsky Method (2021)

Awards and nominations

Main article: List of awards and nominations received by Morgan Freeman

Freeman has been recognized by the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences for the following performances:

- 60th Academy Awards: Best Supporting Actor, nomination, for Street Smart (1987)[34]

- 62nd Academy Awards: Best Actor, nomination, for Driving Miss Daisy (1989)[37]

- 67th Academy Awards: Best Actor, nomination, for The Shawshank Redemption (1994)[55]

- 77th Academy Awards: Best Supporting Actor, win, for Million Dollar Baby (2004)[255]

- 82nd Academy Awards: Best Actor, nomination, for Invictus (2009)[256]

Freeman has been nominated for five Golden Globe Awards, winning one for Best Actor in Driving Miss Daisy (1989).[257] He has also been nominated for three Screen Actors Guild Awards, winning one for Outstanding Performance by a Male Actor in a Supporting Role in Million Dollar Baby (2004).[258] He earned an Obie Award for each theater role in Coriolanus (1979), Mother Courage and Her Children (1980), and Driving Miss Daisy (1987–90).[16]

See also

References

- ^ “12/09/2008”. The Film Programme. September 12, 2008. BBC Radio 4. Archived from the original on February 4, 2011. Retrieved January 18, 2014.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Ross, Harold Wallace; White, Katharine Sergeant Angell (July 3, 1978). “Interview with Morgan Freeman”. The New Yorker. [My grandmother] had been married to Morgan Herbert Freeman, and my father was Morgan Porterfield Freeman, but they forgot to give me a middle name. Archived from the original on March 20, 2021. Retrieved March 20, 2021.

- ^ “Empire’s 50 Greatest Actors Of All Time List, Revealed”. Empire. December 20, 2022. Retrieved June 22, 2024.

- ^ “Morgan Freeman names his favourite actors of all time”. Far Out Magazine. April 14, 2023. Retrieved June 22, 2024.

- ^ Steinbeiser, Andrew (June 1, 2015). “Happy Birthday! Morgan Freeman Turns 78 Today”. ComicBook.com. Archived from the original on June 1, 2015. Retrieved June 1, 2015.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “Morgan Freeman profile”. African American Lives 2. PBS. Archived from the original on August 14, 2011. Retrieved July 13, 2011.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Tracy, Kathleen (2006). Morgan Freeman : a biography. Fort Lee, N.J.: Barricade Books. pp. 7–9, 14. ISBN 978-1-56980-307-3. OCLC 69672088. Archived from the original on March 20, 2021. Retrieved March 20, 2021.

- ^ DeAngelis, Gina (2000). Morgan Freeman. Philadelphia: Chelsea House Publishers. p. 12. ISBN 0-7910-4963-9. OCLC 40862074. Archived from the original on March 20, 2021. Retrieved March 20, 2021.

- ^ Gates, Henry L. Jr. (2009). In Search of Our Roots: How 19 Extraordinary African Americans Reclaimed Their Past. Crown. ISBN 9780307409737. Archived from the original on March 20, 2021. Retrieved October 17, 2020.

- ^ “Profiles: Morgan Freeman”. Hello. London, England. October 8, 2009. Archived from the original on May 27, 2018. Retrieved May 27, 2018.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e Lipton, James (host) (January 2, 2005). “Morgan Freeman”. Inside the Actors Studio. Season 11. Episode 10. Bravo.

- ^ “Morgan Freeman: Full Biography,” Archived June 2, 2013, at the Wayback Machine All Movie Guide, via The New York Times.. Retrieved October 9, 2012.

- ^ Blumberg, Antonia (May 5, 2016). “Morgan Freeman Explains How God Can Be Real And An Invention”. The Huffington Post. New York City: Huffington Post Media Group. Archived from the original on March 20, 2021. Retrieved March 23, 2017.

- ^ “TogetherWeServed – A1C Morgan Porterfield Freeman”. togetherweserved.com. Archived from the original on May 4, 2014. Retrieved August 23, 2015.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Whitaker, Charles (April 1990). “Is Morgan Freeman America’s Greatest Actor?”. Ebony: 32–34. ISSN 0012-9011.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f g Young, Jeff C. (2013). Amazing African-American actors. New York: Enslow Publishers, Inc. pp. 57–61. ISBN 978-1-59845-135-1. OCLC 726695810. Archived from the original on March 20, 2021. Retrieved August 1, 2020.

- ^ Morgan Freeman Biography Archived April 3, 2007, at the Wayback Machine. tiscali.co.uk

- ^ “HELLO, DOLLY! (1967 BROADWAY CAST)”. Sony Music Entertainment. Archived from the original on May 25, 2018. Retrieved May 24, 2018.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Weber, Bruce (April 20, 2008). “Driving Mr. Freeman Back Onstage”. The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 20, 2021. Retrieved July 30, 2020.

- ^ Joan Ganz Cooney discusses the beginnings of “The Electric Company”- EMMYTVLEGENDS. YouTube. October 21, 2011. Archived from the original on September 27, 2011. Retrieved August 23, 2015.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Morgan Freeman talks ‘Street Smart’, winning an Oscar and reveals that acting isn’t hard. YouTube. August 21, 2014. Archived from the original on March 16, 2016. Retrieved August 23, 2015.

- ^ Morales, Tatiana (January 15, 2004). “Morgan Freeman’s ‘Big Bounce'”. CBS News. Archived from the original on March 20, 2021. Retrieved July 30, 2020.

- ^ Eder, Richard (April 17, 1978). “Stage: The Mighty Gents'”. The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on February 1, 2018. Retrieved July 29, 2020.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Bettinger, Brendan (October 12, 2010). “AFI to Present Morgan Freeman with the Life Achievement Award”. Collider. Archived from the original on March 20, 2021. Retrieved July 29, 2020.

- ^ “Pacino, Streep, Kline, Portman, Freeman, Goldblum, Sheen and More! Celebrating 50+ Years of Shakespeare in the Park”. Playbill. Archived from the original on October 29, 2014. Retrieved July 30, 2020.

- ^ “Brubaker (1980)”. Rotten Tomatoes. June 20, 1980. Archived from the original on May 6, 2019. Retrieved July 30, 2020.

- ^ “Morgan Freeman”. CNN. January 22, 2018. Retrieved July 30, 2020.

- ^ Canby, Vincent (February 27, 1981). “William Hurt in ‘Eyewitness'”. The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on January 7, 2015. Retrieved July 30, 2020.

- ^ Fearn-Banks, Kathleen. (2009). The A to Z of African-American television. Fearn-Banks, Kathleen. Lanham: Scarecrow Press. p. 151. ISBN 978-0-8108-6348-4. OCLC 435778789.

- ^ Ebert, Roger. “Marie: A True Story movie review (1985) | Roger Ebert”. Roger Ebert. Archived from the original on October 28, 2014. Retrieved July 30, 2020.

- ^ Hal Erickson (2016). “The Atlanta Child Murders (1985)”. Movies & TV Dept. The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 25, 2016. Retrieved October 28, 2020.

- ^ Blau, Robert (November 8, 1985). “‘That was then. . .’ A teen story for now”. Chicago Tribune. Retrieved July 30, 2020.

- ^ “Reviews: Street Smart”. rogerebert.com. Archived from the original on August 4, 2020. Retrieved July 13, 2020.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “The 60th Academy Awards | 1988”. Oscars.org | Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. December 4, 2015. Archived from the original on July 24, 2020. Retrieved July 25, 2020.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (August 10, 1998). “Clean and Sober movie review & film summary (1988) | Roger Ebert”. Roger Ebert. Archived from the original on July 8, 2020. Retrieved July 25, 2020.

- ^ Howe, Desson (January 12, 1990). “Glory (R)”. The Washington Post. Archived from the original on September 14, 2019. Retrieved July 25, 2020.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c “The 62nd Academy Awards | 1990”. Oscars.org | Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. October 5, 2014. Archived from the original on April 11, 2020. Retrieved July 25, 2020.

- ^ “Driving Miss Daisy”. Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on August 3, 2020. Retrieved July 25, 2020.

- ^ Sheehan, Henry (December 11, 1989). “‘Driving Miss Daisy’: THR’s 1989 Review”. The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on July 28, 2020. Retrieved July 25, 2020.

- ^ Galbraith, Jane (February 1, 1989). “Lean on Me”. Variety. Archived from the original on May 9, 2019. Retrieved July 25, 2020.

- ^ Ebert, Roger. “Johnny Handsome movie review & film summary (1989) | Roger Ebert”. Roger Ebert. Archived from the original on October 29, 2014. Retrieved July 29, 2020.

- ^ Lee-Wright, Peter. (2010). The documentary handbook. London: Routledge. p. 185. ISBN 978-0-203-86719-8. OCLC 562170243. Archived from the original on March 20, 2021. Retrieved August 1, 2020.

- ^ “The Bonfire of the Vanities (1990)”. Rotten Tomatoes. August 10, 2010. Archived from the original on March 20, 2021. Retrieved July 25, 2020.

- ^ Rothstein, Mervyn (June 19, 1990). “Taking Shakespeare’s Shrew To the Old West of the Late 1800’s”. The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 20, 2021. Retrieved July 29, 2020.

- ^ “Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves”. Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on December 8, 2019. Retrieved July 25, 2020.

- ^ Canby, Vincent (June 14, 1991). “Review/Film; A Polite Robin Hood In a Legend Recast”. The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 20, 2021. Retrieved July 25, 2020.

- ^ “Videos glorious news for civil war buffs”. Arizona Republic. June 21, 1991.

- ^ “The 65th Academy Awards | 1993”. Oscars.org | Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. October 4, 2014. Archived from the original on April 16, 2020. Retrieved July 25, 2020.

- ^ Byrge, Duane (July 31, 1992). “‘Unforgiven’: THR’s 1992 Review”. The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on March 20, 2021. Retrieved July 25, 2020.

- ^ Maslin, Janet (March 27, 1992). “Movie Review – The Power of One – Review/Film; A Youngster Against The Power of Apartheid”. The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 25, 2014. Retrieved July 31, 2020.

- ^ Hinson, Hal (September 24, 1993). “Bopha!”. The Washington Post. Archived from the original on March 20, 2021. Retrieved July 26, 2020.

- ^ Turan, Kenneth (September 24, 1993). “Movie Review : ‘Bopha!’: Familiar Setting, Familiar Story”. Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on July 26, 2020. Retrieved July 26, 2020.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Heidenry, Margaret (September 22, 2014). “The Little-Known Story of How The Shawshank Redemption Became One of the Most Beloved Films of All Time”. Vanity Fair. Archived from the original on February 26, 2019. Retrieved July 26, 2020.

- ^ Maslin, Janet (September 23, 1994). “Film Review; Prison Tale by Stephen King Told Gently, Believe It or Not”. The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on July 26, 2020. Retrieved July 26, 2020.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “The 67th Academy Awards | 1995”. Oscars.org | Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. October 5, 2014. Archived from the original on May 10, 2019. Retrieved July 26, 2020.

- ^ “Berlinale: 1994 Juries”. berlinale.de. Archived from the original on October 15, 2013. Retrieved June 9, 2011.

- ^ “Outbreak”. Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on July 26, 2020. Retrieved July 26, 2020.

- ^ “Outbreak (1995)”. Rotten Tomatoes. August 27, 1997. Archived from the original on July 8, 2020. Retrieved July 26, 2020.

- ^ LaSalle, Mick (March 10, 1995). “Dustin Hoffman Thriller Nothing to Sneeze At”. SFGate. Archived from the original on March 20, 2021. Retrieved July 26, 2020.

- ^ Gleiberman, Owen (September 29, 1995). “Seven”. Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on July 26, 2020. Retrieved July 26, 2020.

- ^ “Se7en Review”. Variety. January 1, 1995. Archived from the original on May 26, 2009. Retrieved November 18, 2020.

- ^ Longwell, Todd (December 7, 2017). “Morgan Freeman’s Biggest Revelation: He Could Shape His Own Destiny”. Variety. Archived from the original on August 4, 2019. Retrieved July 31, 2020.

- ^ “Chain Reaction (1996)”. Rotten Tomatoes. August 2, 1996. Archived from the original on July 27, 2020. Retrieved July 26, 2020.

- ^ “Chain Reaction”. Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on August 4, 2020. Retrieved July 26, 2020.

- ^ Evans, Greg (May 24, 1996). “Moll Flanders”. Variety. Archived from the original on July 26, 2020. Retrieved July 26, 2020.

- ^ Holden, Stephen (June 14, 1996). “Film Review;Complicated Life Redeemed by Love (Published 1996)”. The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 20, 2021. Retrieved October 18, 2020.

- ^ “The 70th Academy Awards | 1998”. Oscars.org | Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. October 5, 2014. Archived from the original on June 2, 2019. Retrieved July 26, 2020.

- ^ “Amistad (1997)”. Rotten Tomatoes. December 10, 1997. Archived from the original on July 30, 2020. Retrieved July 26, 2020.

- ^ Taylor, Charles (December 12, 1997). “Amistad”. Salon. Archived from the original on March 14, 2011. Retrieved July 26, 2020.

- ^ Stack, Peter (October 3, 1997). “Film Review — Freeman, Judd Save the ‘Girls’ / Creepy thriller about sexual sadist”. SFGate. Archived from the original on July 26, 2020. Retrieved July 26, 2020.

- ^ “Morgan Freeman as President Tim Beck | Top 10 Movie Presidents”. Time. October 16, 2008. ISSN 0040-781X. Archived from the original on December 21, 2019. Retrieved July 31, 2020.

- ^ “Deep Impact”. Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on July 26, 2020. Retrieved July 26, 2020.

- ^ Van Gelder, Lawrence (January 16, 1998). “Film Review; Outlook: Stormy (It’s Raining, Too)”. The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 20, 2021. Retrieved July 26, 2020.

- ^ Levy, Emanuel (May 12, 2000). “Nurse Betty”. Variety. Archived from the original on January 23, 2018. Retrieved July 26, 2020.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “BBC – Films – interview – Morgan Freeman”. BBC. January 11, 2001. Archived from the original on July 26, 2020. Retrieved July 26, 2020.

- ^ “Under Suspicion”. Metacritic. Archived from the original on March 20, 2021. Retrieved November 12, 2020.

- ^ Tatara, Paul (September 22, 2000). “CNN – Entertainment – Compelling, but … – September 22, 2000”. CNN. Archived from the original on March 20, 2021. Retrieved July 26, 2020.

- ^ “Along Came a Spider (2001)”. Rotten Tomatoes. April 6, 2001. Archived from the original on December 28, 2019. Retrieved July 26, 2020.

- ^ Wloszczyna, Susan (June 4, 2001). “‘Spider’ crawls along without enough venom”. USA Today. Archived from the original on November 30, 2017. Retrieved July 26, 2020.

- ^ “The Sum of All Fears (2002)”. Rotten Tomatoes. May 31, 2002. Retrieved November 11, 2020.

- ^ “The Sum of All Fears”. Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on July 26, 2020. Retrieved July 26, 2020.

- ^ Smith, Neil (October 21, 2002). “BBC – Films – review – High Crimes”. BBC. Retrieved July 26, 2020.

- ^ O’Sullivan, Michael (April 4, 2002). “‘High Crimes’: A Guilty Pleasure”. The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved July 26, 2020.

- ^ Hughes, Scott (June 20, 2003). “God – The Hollywood years”. The Guardian. Retrieved November 11, 2020.

- ^ “Dreamcatcher”. Box Office Mojo. Retrieved November 11, 2020.

- ^ “Dreamcatcher (2003)”. Rotten Tomatoes. March 21, 2003. Archived from the original on January 4, 2020. Retrieved July 26, 2020.

- ^ “Levity (2003)”. Movies & TV Dept. The New York Times. 2015. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on January 7, 2015. Retrieved November 11, 2020.

- ^ Patrizio, Andy (July 21, 2003). “Guilty by Association – IGN”. IGN (published November 24, 2018). Retrieved November 11, 2020.

- ^ “The Big Bounce (2004)”. Rotten Tomatoes. January 29, 2004. Retrieved November 11, 2020.

- ^ “Million Dollar Baby (2004)”. Rotten Tomatoes. December 15, 2004. Retrieved November 11, 2020.

- ^ “Million Dollar Baby”. www.goldenglobes.com. Archived from the original on July 26, 2020. Retrieved July 26, 2020.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (December 14, 2004). “Million Dollar Baby movie review (2005) | Roger Ebert”. Roger Ebert. Archived from the original on July 25, 2020. Retrieved July 26, 2020.

- ^ Andrew, Geoff (June 24, 2006). “Million Dollar Baby”. Time Out Worldwide. Archived from the original on July 27, 2020. Retrieved July 26, 2020.

- ^ Brooks, Xan (June 16, 2006). “An Unfinished Life”. The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on July 26, 2020. Retrieved July 26, 2020.

- ^ Dargis, Manohla (June 15, 2005). “Dark Was the Young Knight Battling His Inner Demons”. The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on June 17, 2020. Retrieved July 31, 2020.

- ^ Hartlaub, Peter (May 13, 2005). “Jet Li takes a bold leap”. SFGate. Archived from the original on July 26, 2020. Retrieved July 26, 2020.

- ^ “Edison”. Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on July 26, 2020. Retrieved July 26, 2020.

- ^ Esposito, Michael (September 23, 2005). “IMAX beats NASA back to the moon”. Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on June 13, 2020. Retrieved July 31, 2020.

- ^ Cornelius, John (July 24, 2007). “The Contract”. DVD Talk. Archived from the original on December 9, 2017. Retrieved July 31, 2020.

- ^ “Lucky Number Slevin (2006)”. Rotten Tomatoes. April 7, 2006. Archived from the original on May 23, 2019. Retrieved November 11, 2020.

- ^ Mattin, David (February 23, 2006). “BBC – Movies – review – Lucky Number Slevin”. BBC. Retrieved July 27, 2020.

- ^ Scott, A. O. (December 1, 2006). “Lingering on the Express Line: Bagging Some Humanity Amid Bar-Code Scanners (Published 2006)”. The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on March 20, 2021. Retrieved November 11, 2020.

- ^ “Morgan Freeman to release new film online two weeks after theater opening NEW YORK (AP) – Just two weeks after “10 Items or Less” opens in theaters Friday, it’ll be available for digital download from Clickstar, a company that Morgan Freeman'”. The Mercury News. November 30, 2006. Archived from the original on July 27, 2020. Retrieved July 27, 2020.

- ^ “Evan Almighty”. Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on March 20, 2021. Retrieved November 11, 2020.

- ^ “Evan Almighty”. Metacritic. Archived from the original on March 20, 2021. Retrieved November 12, 2020.

- ^ O’Neill, Phelim (August 2, 2007). “Evan Almighty”. The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Archived from the original on July 27, 2020. Retrieved July 27, 2020.

- ^ Bradshaw, Peter (October 4, 2007). “Feast of Love”. The Guardian. Archived from the original on July 27, 2020. Retrieved July 27, 2020.

- ^ “Gone Baby Gone”. Time Out Worldwide. June 3, 2008. Archived from the original on July 27, 2020. Retrieved July 27, 2020.

- ^ French, Philip (February 17, 2008). “Review: The Bucket List”. The Observer. ISSN 0029-7712. Archived from the original on March 20, 2021. Retrieved July 31, 2020.

- ^ “The Bucket List”. Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on July 27, 2020. Retrieved July 27, 2020.

- ^ Morales, Wilson (June 23, 2008). “June 2008 | blackfilm.com | Wanted: An Exclusive Interview with Commonn”. www.blackfilm.com. Archived from the original on June 21, 2010. Retrieved July 27, 2020.

- ^ Howell, Peter (June 27, 2008). “Wanted: Bullet-bending thriller”. Toronto Star. Archived from the original on July 27, 2020. Retrieved July 27, 2020.

- ^ Corliss, Richard (June 19, 2008). “Love Guru: Transcendent … Not!”. Time. ISSN 0040-781X. Archived from the original on March 20, 2021. Retrieved November 11, 2020.

- ^ Alexander, Bryan (August 26, 2016). “Morgan Freeman surprised by Batman announcement”. USA Today. Archived from the original on March 20, 2021. Retrieved July 31, 2020.

- ^ The Country Girl. “The Country Girl – Broadway Play – 2008 Revival | IBDB”. Internet Broadway Database. Archived from the original on March 20, 2021. Retrieved July 29, 2020.

- ^ “Thick as Thieves (The Code) (2009)”. Rotten Tomatoes. June 23, 2009. Archived from the original on April 2, 2019. Retrieved July 31, 2020.

- ^ Gumbel, Andrew (September 26, 2007). “Morgan Freeman to play Mandela in new film”. The Independent.

- ^ “Morgan Freeman talks about making ‘Invictus’ and playing Mandela”. TheGrio. Los Angeles, California: Entertainment Studios. December 12, 2012. Archived from the original on July 11, 2018. Retrieved May 26, 2018.

- ^ Keller, Bill (August 17, 2008). “Entering the Scrum”. The New York Times Book Review. Archived from the original on June 2, 2013. Retrieved May 26, 2018.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (December 9, 2009). “South Africa’s messiah as rugby fan”. rogerebert.com. Archived from the original on August 4, 2020. Retrieved July 14, 2020.

- ^ “Academy Award nominations”. Variety. February 2, 2010. Archived from the original on July 27, 2020. Retrieved July 27, 2020.

- ^ “67th Annual Golden Globes winners list”. Variety. January 18, 2010. Archived from the original on July 27, 2020. Retrieved July 27, 2020.

- ^ Barraclough, Leo (December 17, 2009). “SAG nominations list”. Variety. Archived from the original on July 27, 2020. Retrieved July 27, 2020.

- ^ Milloy, Courtland (June 14, 2009). “Courtland Milloy on the Debut of ‘Anne and Emmett'”. The Washington Post. Archived from the original on April 29, 2019. Retrieved September 7, 2020.

- ^ Sciretta, Peter (July 19, 2009). “Morgan Freeman Joins The Big Screen Adaptation of Warren Ellis’ Red”. /Film. Archived from the original on September 9, 2012. Retrieved January 19, 2010.

- ^ “RED”. Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on March 20, 2021. Retrieved July 27, 2020.

- ^ Schembri, Jim (October 27, 2010). “RED”. The Age. Archived from the original on June 5, 2020. Retrieved July 27, 2020.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “Freeman replaces Cronkite on CBS news”. Boston Globe. January 5, 2010. Archived from the original on March 20, 2021. Retrieved January 5, 2010.

- ^ Halterman, Jim (June 9, 2010). “Interview: “Through the Wormhole with Morgan Freeman” Executive Producer Bernadette Mcdaid”. The Futon Critic. Retrieved July 29, 2020.

- ^ Trumbore, Dave (September 11, 2014). “Morgan Freeman Talks Dolphin Tale 2, Returning to Play the Snarky Dr. McCarthy, Reuniting with Winter, and Comments on the Late Nelson Mandela”. Collider. Retrieved July 31, 2020.

- ^ Cassens Weiss, Debra (September 20, 2011). “Proposition 8 Play Features Morgan Freeman and John Lithgow as Litigators Boies and Olson”. ABA Journal. Chicago, Illinois. Archived from the original on December 29, 2011. Retrieved March 17, 2012.

- ^ “‘8’: A Play about the Fight for Marriage Equality”. YouTube. American Foundation for Equal Rights. March 4, 2012. Archived from the original on March 15, 2012. Retrieved March 18, 2012.

- ^ Gray, Stephen (March 1, 2012). “YouTube to broadcast Proposition 8 play live”. Pink News. London, England. Archived from the original on March 4, 2012. Retrieved March 18, 2012.

- ^ “The Magic of Belle Isle (2012)”. Rotten Tomatoes. July 6, 2012. Archived from the original on May 6, 2019. Retrieved July 27, 2020.

- ^ Carlston, Eric (July 19, 2012). “‘Dark Knight Rises’ Star Morgan Freeman Sounds Off on Pot Legalization, Gay Marriage”. The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on January 22, 2015. Retrieved July 31, 2020.

- ^ “Olympus Has Fallen”. Box Office Mojo. Retrieved August 1, 2020.

- ^ LaSalle, Mick (March 21, 2013). “‘Olympus Has Fallen’ review: Satisfying”. SFGate. Retrieved October 20, 2020.

- ^ “Oblivion”. Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on March 20, 2021. Retrieved August 1, 2020.

- ^ “Now You See Me”. Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on February 28, 2020. Retrieved August 1, 2020.

- ^ “Last Vegas”. Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on March 20, 2021. Retrieved August 1, 2020.

- ^ Christine, Bord (November 28, 2012). “‘Last Vegas’ looking for Extras in Atlanta”. On Location Vacations. Archived from the original on March 20, 2021. Retrieved October 20, 2020.

- ^ Bowles, Scott (October 31, 2013). “‘Last Vegas’ can’t putter past story predictability”. USA Today. Archived from the original on March 20, 2021. Retrieved October 20, 2020.

- ^ “The Lego Movie”. Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on July 31, 2020. Retrieved July 27, 2020.

- ^ “Transcendence”. Metacritic. Archived from the original on March 20, 2021. Retrieved November 12, 2020.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Lucy Production Notes Archived August 1, 2014, at the Wayback Machine (PDF). Universal Pictures. Retrieved July 27, 2020.

- ^ “Lucy (2014)”. Rotten Tomatoes. July 25, 2014. Archived from the original on April 30, 2020. Retrieved July 27, 2020.

- ^ Trumbore, Dave (September 11, 2014). “Morgan Freeman Talks Dolphin Tale 2, Returning to Play the Snarky Dr. McCarthy, Reuniting with Winter, and Comments on the Late Nelson Mandela”. Collider. Archived from the original on October 28, 2014. Retrieved November 11, 2020.

- ^ Barker, Andrew (September 6, 2014). “Toronto Film Review: ‘Ruth & Alex'”. Variety. Archived from the original on January 8, 2015. Retrieved November 11, 2020.

- ^ Falkner, Scott (December 22, 2014). “Lennon Or McCartney? New Documentary Asks 550 Celebrities Their Preference — See Their Answers”. www.inquisitr.com. Archived from the original on July 27, 2020. Retrieved July 31, 2020.

- ^ “Last Knights”. Metacritic. Archived from the original on March 20, 2021. Retrieved November 12, 2020.

- ^ Stewart, Sara (April 1, 2015). “Freeman, Owen casualties of bloody bad ‘Last Knights'”. New York Post. Archived from the original on January 27, 2020. Retrieved July 28, 2020.

- ^ Kroll, Justin (September 10, 2014). “Morgan Freeman Lands Juicy Role in ‘Ted 2’ (EXCLUSIVE)”. Variety. Archived from the original on September 11, 2014. Retrieved July 31, 2020.

- ^ Keveney, Bill. “Morgan Freeman has double duty in CBS’ ‘Madam Secretary'”. USA Today. Archived from the original on March 20, 2021. Retrieved July 31, 2020.

- ^ Keveney, Bill (October 1, 2015). “Morgan Freeman has double duty in CBS’ ‘Madam Secretary'”. USA Today. Archived from the original on March 20, 2021. Retrieved July 29, 2020.

- ^ “Morgan Freeman thriller loses Momentum taking £4.60 per cinema”. The Guardian. November 24, 2015. Archived from the original on July 16, 2019. Retrieved July 31, 2020.

- ^ “London Has Fallen”. Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on May 20, 2020. Retrieved July 28, 2020.

- ^ Vishnevetsky, Ignatiy (March 2, 2016). “Gerard Butler scowls his way through the atrocious London Has Fallen”. A.V. Club. Archived from the original on July 28, 2020. Retrieved July 28, 2020.

- ^ Gill, James (January 20, 2015). “First look at Daniel Radcliffe in magic heist Now You See Me 2”. Radio Times. Archived from the original on March 20, 2021. Retrieved November 11, 2020.

- ^ “Now You See Me 2”. Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on June 27, 2020. Retrieved July 28, 2020.

- ^ Kolbert, Elizabeth (August 1, 2016). “Morgan Freeman’s “Ben-Hur””. The New Yorker. Archived from the original on August 4, 2016. Retrieved July 28, 2020.

- ^ Boardman, Madeline (January 2, 2017). “The Biggest Box Office Flops of 2016”. Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved September 17, 2024.

- ^ McClintock, Pamela; Galuppo, Mia (December 29, 2016). “‘Ben Hur’ to ‘BFG’: Hollywood’s Biggest Box-Office Bombs of 2016”. The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved September 17, 2024.

- ^ Pedersen, Erik (January 12, 2016). “Warner Bros Moves Key & Peele Starrer ‘Keanu’ Back One Week – Update”. Deadline. Archived from the original on July 25, 2020. Retrieved July 31, 2020.

- ^ “Going in Style”. Metacritic. Archived from the original on October 27, 2017. Retrieved November 12, 2020.

- ^ Collin, Robbie (April 6, 2017). “Going in Style: Michael Caine and Morgan Freeman go nowhere in this benignly boring comedy – review”. The Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Archived from the original on July 28, 2020. Retrieved July 28, 2020.

- ^ “Just Getting Started (2017)”. Rotten Tomatoes. December 8, 2017. Archived from the original on August 1, 2020. Retrieved July 28, 2020.

- ^ Petski, Denise (June 11, 2015). “Morgan Freeman To Host & Produce ‘The Story Of God’ For Nat Geo”. Deadline. Archived from the original on March 20, 2021. Retrieved July 31, 2020.

- ^ Truitt, Brian. “10 burning questions you might have about Disney’s new live-action ‘Nutcracker’ movie”. USA Today. Archived from the original on March 20, 2021. Retrieved July 31, 2020.

- ^ Farber, Stephen (September 26, 2018). “‘Brian Banks’: Film Review | LAFF 2018”. The Hollywood Reporter. Archived from the original on March 20, 2021. Retrieved July 31, 2020.

- ^ Wilson, Lisa (June 6, 2018). “Savannah film behind-the-scenes: Actress praises Morgan Freeman. Travolta plays poker”. The Island Packet. Archived from the original on July 1, 2018. Retrieved July 31, 2020.

- ^ “Angel Has Fallen (2019)”. Rotten Tomatoes. Archived from the original on August 22, 2019. Retrieved November 11, 2020.

- ^ “Angel Has Fallen”. Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on July 28, 2020. Retrieved July 28, 2020.

- ^ “Eddie Murphy Says “Coming To America” Sequel Will Make His Daughter A Star”. AllHipHop.com. Archived from the original on March 7, 2021. Retrieved August 1, 2020.

- ^ Young, Alex (November 20, 2022). “Qatar kick off World Cup 2022 with Morgan Freeman and BTS star Jung Kook”. Evening Standard. Retrieved November 20, 2022.

- ^ Summerscales, Robert (November 20, 2022). “Morgan Freeman Performs At World Cup Opening Ceremony In Qatar”. Sports Illustrated. Retrieved November 20, 2022.