PUTIN

Main menu

Personal tools

Contents

hide

- (Top)

- Early lifeToggle Early life subsection

- Intelligence career

- Political careerToggle Political career subsection

- Domestic policiesToggle Domestic policies subsection

- Foreign policyToggle Foreign policy subsection

- Public imageToggle Public image subsection

- AssessmentsToggle Assessments subsection

- Electoral history

- Personal lifeToggle Personal life subsection

- Awards and honours

- Explanatory notes

- ReferencesToggle References subsection

- External links

Vladimir Putin

227 languages

Tools

Appearancehide

Text

- SmallStandardLarge

Width

- StandardWide

Color (beta)

- AutomaticLightDark

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

“Putin” redirects here. For other uses, see Putin (disambiguation).

| This article may be too long to read and navigate comfortably. When this tag was added, its readable prose size was 19,000 words. Consider splitting content into sub-articles, condensing it, or adding subheadings. Please discuss this issue on the article’s talk page. (November 2024) |

| Vladimir Putin | |

|---|---|

| Владимир Путин | |

| Putin in 2024 | |

| President of Russia | |

| Incumbent | |

| Assumed office 7 May 2012 | |

| Prime Minister | Dmitry MedvedevMikhail Mishustin |

| Preceded by | Dmitry Medvedev |

| In office 7 May 2000 – 7 May 2008 Acting: 31 December 1999 – 7 May 2000 | |

| Prime Minister | Mikhail KasyanovMikhail FradkovViktor Zubkov |

| Preceded by | Boris Yeltsin |

| Succeeded by | Dmitry Medvedev |

| Prime Minister of Russia | |

| In office 8 May 2008 – 7 May 2012 | |

| President | Dmitry Medvedev |

| First Deputy | Sergei IvanovViktor ZubkovIgor Shuvalov |

| Preceded by | Viktor Zubkov |

| Succeeded by | Viktor Zubkov (acting) |

| In office 9 August 1999 – 7 May 2000 | |

| President | Boris Yeltsin |

| First Deputy | Nikolay AksyonenkoViktor KhristenkoMikhail Kasyanov |

| Preceded by | Sergei Stepashin |

| Succeeded by | Mikhail Kasyanov |

| Secretary of the Security Council of Russia | |

| In office 9 March 1999 – 9 August 1999 | |

| Chairman | Boris Yeltsin |

| Preceded by | Nikolay Bordyuzha |

| Succeeded by | Sergei Ivanov |

| Director of the Federal Security Service | |

| In office 25 July 1998 – 29 March 1999 | |

| President | Boris Yeltsin |

| Preceded by | Nikolay Kovalyov |

| Succeeded by | Nikolai Patrushev |

| First Deputy Chief of the Presidential Administration | |

| In office 25 May 1998 – 24 July 1998 | |

| President | Boris Yeltsin |

| Deputy Chief of the Presidential Administration – Head of the Main Supervisory Department | |

| In office 26 March 1997 – 24 May 1998 | |

| President | Boris Yeltsin |

| Preceded by | Alexei Kudrin |

| Succeeded by | Nikolai Patrushev |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Vladimir Vladimirovich Putin 7 October 1952 (age 72) Leningrad, Russian SFSR, Soviet Union |

| Political party | Independent (1991–1995, 2001–2008, 2012–present) |

| Other political affiliations | People’s Front (2011–present)United Russia[1] (2008–2012)Unity (1999–2001)Our Home – Russia (1995–1999)CPSU (1975–1991) |

| Height | 170 cm (5 ft 7 in) |

| Spouse | Lyudmila Shkrebneva(m. 1983; div. 2014)[a] |

| Children | At least 2, Maria and Katerina[b] |

| Relatives | Putin family |

| Residence(s) | Novo-Ogaryovo, Moscow |

| Alma mater | Leningrad State University (LLB)Leningrad Mining Institute (Kandidat Nauk) |

| Awards | Full list |

| Signature | |

| Website | eng.putin.kremlin.ru |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | Soviet Union Russia |

| Branch/service | KGBFSBRussian Armed Forces |

| Years of service | 1975–19911997–19992000–present |

| Rank | Colonel1st class Active State Councillor of the Russian Federation |

| Commands | Supreme Commander-in-Chief |

| Battles/wars | Second Chechen WarRusso-Georgian WarRusso-Ukrainian WarSyrian Civil WarCentral African Republic Civil War |

| Vladimir Putin’s voiceDuration: 28 minutes and 4 seconds.28:04Putin declaring a “special military operation” in Ukraine Recorded 24 February 2022 | |

Vladimir Vladimirovich Putin[c][d] (born 7 October 1952) is a Russian politician and former intelligence officer who has served as President of Russia since 2012, having previously served from 2000 to 2008. Putin also served as Prime Minister of Russia from 1999 to 2000[e] and again from 2008 to 2012.[f][7] At 24 years, 11 months and 12 days, he is the longest-serving Russian or Soviet leader since the 30-year tenure of Joseph Stalin.

Putin worked as a KGB foreign intelligence officer for 16 years, rising to the rank of lieutenant colonel. He resigned in 1991 to begin a political career in Saint Petersburg. In 1996, he moved to Moscow to join the administration of President Boris Yeltsin. He briefly served as the director of the Federal Security Service (FSB) and then as secretary of the Security Council of Russia before being appointed prime minister in August 1999. Following Yeltsin’s resignation, Putin became acting president and, in less than four months, was elected to his first term as president. He was reelected in 2004. Due to constitutional limitations of two consecutive presidential terms, Putin served as prime minister again from 2008 to 2012 under Dmitry Medvedev. He returned to the presidency in 2012, following an election marked by allegations of fraud and protests, and was reelected in 2018.

During Putin’s initial presidential tenure, the Russian economy grew on average by seven percent per year,[8] driven by economic reforms and a fivefold increase in the price of oil and gas.[9][10] Additionally, Putin led Russia in a conflict against Chechen separatists, reestablishing federal control over the region.[11][12] While serving as prime minister under Medvedev, he oversaw a military conflict with Georgia and enacted military and police reforms. In his third presidential term, Russia annexed Crimea and supported a war in eastern Ukraine through several military incursions, resulting in international sanctions and a financial crisis in Russia. He also ordered a military intervention in Syria to support his ally Bashar al-Assad during the Syrian civil war, with the aim of obtaining naval bases in the Eastern Mediterranean.[13][14][15]

In February 2022, during his fourth presidential term, Putin launched a full-scale invasion of Ukraine, which prompted international condemnation and led to expanded sanctions. In September 2022, he announced a partial mobilization and forcibly annexed four Ukrainian oblasts into Russia. In March 2023, the International Criminal Court issued an arrest warrant for Putin for war crimes[16] related to his alleged criminal responsibility for illegal child abductions during the war.[17] In April 2021, after a referendum, he signed into law constitutional amendments that included one allowing him to run for reelection twice more, potentially extending his presidency to 2036.[18][19] In March 2024, he was reelected to another term.

Under Putin’s rule, the Russian political system has been transformed into an authoritarian dictatorship with a personality cult.[20][21][22] His rule has been marked by endemic corruption and widespread human rights violations, including the imprisonment and suppression of political opponents, intimidation and censorship of independent media in Russia, and a lack of free and fair elections.[23][24][25] Russia has consistently received very low scores on Transparency International‘s Corruption Perceptions Index, The Economist Democracy Index, Freedom House‘s Freedom in the World index, and the Reporters Without Borders Press Freedom Index.

Early life

Putin was born on 7 October 1952 in Leningrad, Soviet Union (now Saint Petersburg, Russia),[26] the youngest of three children of Vladimir Spiridonovich Putin (1911–1999) and Maria Ivanovna Putina (née Shelomova; 1911–1998). His grandfather, Spiridon Putin (1879–1965), was a personal cook to Vladimir Lenin and Joseph Stalin.[27][28] Putin’s birth was preceded by the deaths of two brothers: Albert, born in the 1930s, died in infancy, and Viktor, born in 1940, died of diphtheria and starvation in 1942 during the Siege of Leningrad by Nazi Germany‘s forces in World War II.[29][30]

Putin’s father, Vladimir Spiridonovich Putin

Putin’s mother, Maria Ivanovna Shelomova

Putin’s mother was a factory worker, and his father was a conscript in the Soviet Navy, serving in the submarine fleet in the early 1930s. During the early stage of the Nazi invasion of the Soviet Union, his father served in the destruction battalion of the NKVD.[31][32][33] Later, he was transferred to the regular army and was severely wounded in 1942.[34] Putin’s maternal grandmother was killed by the German occupiers of Tver region in 1941, and his maternal uncles disappeared on the Eastern Front during World War II.[35]

Education

On 1 September 1960, Putin started at School No. 193 at Baskov Lane, near his home. He was one of a few in his class of about 45 pupils who were not yet members of the Young Pioneer (Komsomol) organization. At the age of 12, he began to practice sambo and judo.[36] In his free time, he enjoyed reading the works of Karl Marx, Friedrich Engels, and Lenin.[37] Putin attended Saint Petersburg High School 281 with a German language immersion program.[38] He is fluent in German and often gives speeches and interviews in that language.[39][40]

Putin studied law at the Leningrad State University named after Andrei Zhdanov (now Saint Petersburg State University) in 1970 and graduated in 1975.[41] His thesis was on “The Most Favored Nation Trading Principle in International Law”.[42] While there, he was required to join the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU); he remained a member until it ceased to exist in 1991.[43] Putin met Anatoly Sobchak, an assistant professor who taught business law,[g] and who later became the co-author of the Russian constitution. Putin was influential in Sobchak’s career in Saint Petersburg, and Sobchak was influential in Putin’s career in Moscow.[44]

In 1997, Putin received a degree in economics (kandidat ekonomicheskikh nauk) at the Saint Petersburg Mining University for a thesis on energy dependencies and their instrumentalisation in foreign policy.[45][46] His supervisor was Vladimir Litvinenko, who in 2000 and again in 2004 managed his presidential election campaigns in St Petersburg.[47] Igor Danchenko and Clifford Gaddy consider Putin to be a plagiarist according to Western standards. One book from which he copied entire paragraphs is the Russian-language edition of King and Cleland‘s Strategic Planning and Policy (1978).[47] Balzer wrote on the Putin thesis and Russian energy policy and concludes along with Olcott that “The primacy of the Russian state in the country’s energy sector is non-negotiable”, and cites the insistence on majority Russian ownership of any joint-venture, particularly since BASF signed the Gazprom Nord Stream–Yuzhno-Russkoye deal in 2004 with a 49–51 structure, as opposed to the older 50–50 split of British Petroleum‘s TNK-BP project.[48]

Intelligence career

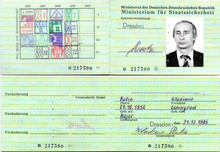

In 1975, Putin joined the KGB and trained at the 401st KGB School in Okhta, Leningrad.[49][50] After training, he worked in the Second Chief Directorate (counterintelligence), before he was transferred to the First Chief Directorate, where he monitored foreigners and consular officials in Leningrad.[49][51][52] In September 1984, Putin was sent to Moscow for further training at the Yuri Andropov Red Banner Institute.[53][54][55]

From 1985 to 1990, he served in Dresden, East Germany,[56] using a cover identity as a translator.[57] While posted in Dresden, Putin worked as one of the KGB’s liaison officers to the Stasi secret police and was reportedly promoted to lieutenant colonel. According to the official Kremlin presidential site, the East German communist regime commended Putin with a bronze medal for “faithful service to the National People’s Army“. Putin has publicly conveyed delight over his activities in Dresden, once recounting his confrontations with anti-communist protestors of 1989 who attempted the occupation of Stasi buildings in the city.[58]

“Putin and his colleagues were reduced mainly to collecting press clippings, thus contributing to the mountains of useless information produced by the KGB”, Russian-American Masha Gessen wrote in their 2012 biography of Putin.[57] His work was also downplayed by former Stasi spy chief Markus Wolf and Putin’s former KGB colleague Vladimir Usoltsev. Journalist Catherine Belton wrote in 2020 that this downplaying was actually cover for Putin’s involvement in KGB coordination and support for the terrorist Red Army Faction, whose members frequently hid in East Germany with the support of the Stasi. Dresden was preferred as a “marginal” town with only a small presence of Western intelligence services.[59] According to an anonymous source who claimed to be a former RAF member, at one of these meetings in Dresden the militants presented Putin with a list of weapons that were later delivered to the RAF in West Germany. Klaus Zuchold, who claimed to be recruited by Putin, said that Putin handled a neo-Nazi, Rainer Sonntag, and attempted to recruit an author of a study on poisons.[59] Putin reportedly met Germans to be recruited for wireless communications affairs together with an interpreter. He was involved in wireless communications technologies in South-East Asia due to trips of German engineers, recruited by him, there and to the West.[52] However, a 2023 investigation by Der Spiegel reported that the anonymous source had never been an RAF member and is “considered a notorious fabulist” with “several previous convictions, including for making false statements”.[60]

According to Putin’s official biography, during the fall of the Berlin Wall that began on 9 November 1989, he saved the files of the Soviet Cultural Center (House of Friendship) and of the KGB villa in Dresden for the official authorities of the would-be united Germany to prevent demonstrators, including KGB and Stasi agents, from obtaining and destroying them. He then supposedly burnt only the KGB files, in a few hours, but saved the archives of the Soviet Cultural Center for the German authorities. Nothing is told about the selection criteria during this burning; for example, concerning Stasi files or about files of other agencies of the German Democratic Republic or of the USSR. He explained that many documents were left to Germany only because the furnace burst but many documents of the KGB villa were sent to Moscow.[62]

After the collapse of the Communist East German government, Putin was to resign from active KGB service because of suspicions aroused regarding his loyalty during demonstrations in Dresden and earlier, although the KGB and the Soviet Army still operated in eastern Germany. He returned to Leningrad in early 1990 as a member of the “active reserves”, where he worked for about three months with the International Affairs section of Leningrad State University, reporting to Vice-Rector Yuriy Molchanov, while working on his doctoral dissertation.[52]

There, he looked for new KGB recruits, watched the student body, and renewed his friendship with his former professor, Anatoly Sobchak, soon to be the Mayor of Leningrad.[63] Putin claims that he resigned with the rank of lieutenant colonel on 20 August 1991,[63] on the second day of the 1991 Soviet coup d’état attempt against Soviet president Mikhail Gorbachev.[64] Putin said: “As soon as the coup began, I immediately decided which side I was on”, although he noted that the choice was hard because he had spent the best part of his life with “the organs”.[65]

Political career

Main articles: Political career of Vladimir Putin and Russia under Vladimir Putin

Further information: Putinism and List of speeches given by Vladimir Putin

See also: Politics of Russia

1990–1996: Saint Petersburg administration

In May 1990, Putin was appointed as an advisor on international affairs to the mayor of Leningrad Anatoly Sobchak. In a 2017 interview with Oliver Stone, Putin said that he resigned from the KGB in 1991, following the coup against Mikhail Gorbachev, as he did not agree with what had happened and did not want to be part of the intelligence in the new administration.[66] According to Putin’s statements in 2018 and 2021, he may have worked as a private taxi driver to earn extra money, or considered such a job.[67][68]

On 28 June 1991, Putin became head of the Committee for External Relations of the Mayor’s Office, with responsibility for promoting international relations and foreign investments[70] and registering business ventures. Within a year, Putin was investigated by the city legislative council led by Marina Salye. It was concluded that he had understated prices and permitted the export of metals valued at $93 million in exchange for foreign food aid that never arrived.[71][41] Despite the investigators’ recommendation that Putin be fired, Putin remained head of the Committee for External Relations until 1996.[72][73] From 1994 to 1996, he held several other political and governmental positions in Saint Petersburg.

In March 1994, Putin was appointed as first deputy chairman of the Government of Saint Petersburg. In May 1995, he organized the Saint Petersburg branch of the pro-government Our Home – Russia political party, the liberal party of power founded by Prime Minister Viktor Chernomyrdin. In 1995, he managed the legislative election campaign for that party, and from 1995 through June 1997, he was the leader of its Saint Petersburg branch.

1996–1999: Early Moscow career

In June 1996, Sobchak lost his bid for re-election in Saint Petersburg, and Putin, who had led his election campaign, resigned from his positions in the city administration. He moved to Moscow and was appointed as deputy chief of the Presidential Property Management Department headed by Pavel Borodin. He occupied this position until March 1997. He was responsible for the foreign property of the state and organized the transfer of the former assets of the Soviet Union and the CPSU to the Russian Federation.[44]

On 26 March 1997, President Boris Yeltsin appointed Putin deputy chief of the Presidential Staff, a post which he retained until May 1998, and chief of the Main Control Directorate of the Presidential Property Management Department (until June 1998). His predecessor in this position was Alexei Kudrin and his successor was Nikolai Patrushev, both future prominent politicians and Putin’s associates.[44] On 3 April 1997, Putin was promoted to 1st class Active State Councillor of the Russian Federation—the highest federal state civilian service rank.[74]

On 27 June 1997, at the Saint Petersburg Mining Institute, guided by rector Vladimir Litvinenko, Putin defended his Candidate of Science dissertation in economics, titled Strategic Planning of the Reproduction of the Mineral Resource Base of a Region under Conditions of the Formation of Market Relations.[75] This exemplified the custom in Russia whereby a young rising official would write a scholarly work in mid-career.[76] Putin’s thesis was plagiarized.[77] Fellows at the Brookings Institution found that 15 pages were copied from an American textbook.[78][79]

On 25 May 1998, Putin was appointed First Deputy Chief of the Presidential Staff for the regions, in succession to Viktoriya Mitina. On 15 July, he was appointed head of the commission for the preparation of agreements on the delimitation of the power of the regions and head of the federal center attached to the president, replacing Sergey Shakhray. After Putin’s appointment, the commission completed no such agreements, although during Shakhray’s term as the head of the Commission 46 such agreements had been signed.[80] Later, after becoming president, Putin cancelled all 46 agreements.[44] On 25 July 1998, Yeltsin appointed Putin director of the Federal Security Service (FSB), the primary intelligence and security organization of the Russian Federation and the successor to the KGB.[81] In 1999, Putin described communism as “a blind alley, far away from the mainstream of civilization”.[82]

1999: First premiership

Further information: Vladimir Putin’s First Cabinet

On 9 August 1999, Putin was appointed one of three first deputy prime ministers, and later on that day, was appointed acting prime minister of the Government of the Russian Federation by President Yeltsin.[83] Yeltsin also announced that he wanted to see Putin as his successor. Later on that same day, Putin agreed to run for the presidency.[84]

On 16 August, the State Duma approved his appointment as prime minister with 233 votes in favor (vs. 84 against, 17 abstained),[85] while a simple majority of 226 was required, making him Russia’s fifth prime minister in fewer than eighteen months. On his appointment, few expected Putin, virtually unknown to the general public, to last any longer than his predecessors. He was initially regarded as a Yeltsin loyalist; like other prime ministers of Boris Yeltsin, Putin did not choose ministers himself, his cabinet was determined by the presidential administration.[86]

Yeltsin’s main opponents and would-be successors were already campaigning to replace the ailing president, and they fought hard to prevent Putin’s emergence as a potential successor. Following the September 1999 Russian apartment bombings and the invasion of Dagestan by mujahideen, including the former KGB agents, based in the Chechen Republic of Ichkeria, Putin’s law-and-order image and unrelenting approach to the Second Chechen War soon combined to raise his popularity and allowed him to overtake his rivals.

While not formally associated with any party, Putin pledged his support to the newly formed Unity Party,[87] which won the second largest percentage of the popular vote (23.3%) in the December 1999 Duma elections, and in turn supported Putin.

1999–2000: Acting presidency

Main article: Putin’s rise to power

On 31 December 1999, Yeltsin unexpectedly resigned and, according to the Constitution of Russia, Putin became Acting President of the Russian Federation. On assuming this role, Putin went on a previously scheduled visit to Russian troops in Chechnya.[88]

The first presidential decree that Putin signed on 31 December 1999 was titled “On guarantees for the former president of the Russian Federation and the members of his family”.[89][90] This ensured that “corruption charges against the outgoing President and his relatives” would not be pursued.[91] This was most notably targeted at the Mabetex bribery case in which Yeltsin’s family members were involved. On 30 August 2000, a criminal investigation (number 18/238278-95) in which Putin himself,[92][93] as a member of the Saint Petersburg city government, was one of the suspects, was dropped.

On 30 December 2000, yet another case against the prosecutor general was dropped “for lack of evidence”, despite thousands of documents having been forwarded by Swiss prosecutors.[94] On 12 February 2001, Putin signed a similar federal law which replaced the decree of 1999. A case regarding Putin’s alleged corruption in metal exports from 1992 was brought back by Marina Salye, but she was silenced and forced to leave Saint Petersburg.[95]

While his opponents had been preparing for an election in June 2000, Yeltsin’s resignation resulted in the presidential elections being held on 26 March 2000; Putin won in the first round with 53% of the vote.[96][97]

2000–2004: First presidential term

See also: Vladimir Putin 2000 presidential campaign

The inauguration of President Putin occurred on 7 May 2000. He appointed the minister of finance, Mikhail Kasyanov, as prime minister.[98] The first major challenge to Putin’s popularity came in August 2000, when he was criticized for the alleged mishandling of the Kursk submarine disaster.[99] That criticism was largely because it took several days for Putin to return from vacation, and several more before he visited the scene.[99]

Between 2000 and 2004, Putin set about the reconstruction of the impoverished condition of the country, apparently winning a power-struggle with the Russian oligarchs, reaching a ‘grand bargain’ with them. This bargain allowed the oligarchs to maintain most of their powers, in exchange for their explicit support for—and alignment with—Putin’s government.[100][101]

The Moscow theater hostage crisis occurred in October 2002. Many in the Russian press and in the international media warned that the deaths of 130 hostages in the special forces’ rescue operation during the crisis would severely damage President Putin’s popularity. However, shortly after the siege had ended, the Russian president enjoyed record public approval ratings—83% of Russians declared themselves satisfied with Putin and his handling of the siege.[102]

In 2003, a referendum was held in Chechnya, adopting a new constitution which declares that the Republic of Chechnya is a part of Russia; on the other hand, the region did acquire autonomy.[103] Chechnya has been gradually stabilized with the establishment of the Parliamentary elections and a Regional Government.[104][105] Throughout the Second Chechen War, Russia severely disabled the Chechen rebel movement; however, sporadic attacks by rebels continued to occur throughout the northern Caucasus.[106]

2004–2008: Second presidential term

See also: Vladimir Putin 2004 presidential campaign

On 14 March 2004, Putin was elected to the presidency for a second term, receiving 71% of the vote.[108] The Beslan school hostage crisis took place on 1–3 September 2004; more than 330 people died, including 186 children.[109]

The near 10-year period prior to the rise of Putin after the dissolution of Soviet rule was a time of upheaval in Russia.[110] In a 2005 Kremlin speech, Putin characterized the collapse of the Soviet Union as the “greatest geopolitical catastrophe of the twentieth century”.[111] Putin elaborated, “Moreover, the epidemic of disintegration infected Russia itself.”[112] The country’s cradle-to-grave social safety net was gone and life expectancy declined in the period preceding Putin’s rule.[113] In 2005, the National Priority Projects were launched to improve Russia’s health care, education, housing, and agriculture.[114][115]

The continued criminal prosecution of the wealthiest man in Russia at the time, president of Yukos oil and gas company Mikhail Khodorkovsky, for fraud and tax evasion was seen by the international press as a retaliation for Khodorkovsky’s donations to both liberal and communist opponents of the Kremlin.[116] Khodorkovsky was arrested, Yukos was bankrupted, and the company’s assets were auctioned at below-market value, with the largest share acquired by the state company Rosneft.[117] The fate of Yukos was seen as a sign of a broader shift of Russia towards a system of state capitalism.[118][119] This was underscored in July 2014, when shareholders of Yukos were awarded $50 billion in compensation by the Permanent Arbitration Court in The Hague.[120]

On 7 October 2006, Anna Politkovskaya, a journalist who exposed corruption in the Russian army and its conduct in Chechnya, was shot in the lobby of her apartment building, on Putin’s birthday. The death of Politkovskaya triggered international criticism, with accusations that Putin had failed to protect the country’s new independent media.[121][122] Putin himself said that her death caused the government more problems than her writings.[123]

In January 2007, Putin met with German Chancellor Angela Merkel at his Black Sea residence in Sochi, two weeks after Russia switched off oil supplies to Germany. Putin brought his black Labrador Konni in front of Merkel, who has a noted phobia of dogs and looked visibly uncomfortable in its presence, adding, “I’m sure it will behave itself”, causing a furor among the German press corps.[124][125] When asked about the incident in a January 2016 interview with Bild, Putin claimed he was not aware of her phobia, adding, “I wanted to make her happy. When I found out that she did not like dogs, I of course apologized.”[126] Merkel later told a group of reporters, “I understand why he has to do this – to prove he’s a man. He’s afraid of his own weakness. Russia has nothing, no successful politics or economy. All they have is this.”[125]

In a speech in February 2007 at the Munich Security Conference, Putin complained about the feeling of insecurity engendered by the dominant position in geopolitics of the United States and observed that a former NATO official had made rhetorical promises not to expand into new countries in Eastern Europe.

On 14 July 2007, Putin announced that Russia would suspend implementation of its Treaty on Conventional Armed Forces in Europe obligations, effective after 150 days,[127][128] and suspend its ratification of the Adapted Conventional Armed Forces in Europe Treaty, which treaty was shunned by NATO members abeyant Russian withdrawal from Transnistria and the Republic of Georgia. Moscow continued to participate in the joint consultative group, because it hoped that dialogue could lead to the creation of an effective, new conventional arms control regime in Europe.[129] Russia did specify steps that NATO could take to end the suspension. “These include [NATO] members cutting their arms allotments and further restricting temporary weapons deployments on each NATO member’s territory. Russia also want[ed] constraints eliminated on how many forces it can deploy in its southern and northern flanks. Moreover, it is pressing NATO members to ratify a 1999 updated version of the accord, known as the Adapted CFE Treaty, and demanding that the four alliance members outside the original treaty, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, and Slovenia, join it.”[128]

In early 2007, “Dissenters’ Marches” were organized by the opposition group The Other Russia,[130] led by former chess champion Garry Kasparov and national-Bolshevist leader Eduard Limonov. Following prior warnings, demonstrations in several Russian cities were met by police action, which included interfering with the travel of the protesters and the arrests of as many as 150 people who attempted to break through police lines.[131]

On 12 September 2007, Putin dissolved the government upon the request of Prime Minister Mikhail Fradkov. Fradkov commented that it was to give the President a “free hand” in the run-up to the parliamentary election. Viktor Zubkov was appointed the new prime minister.[132] On 19 September 2007, Putin’s nuclear-capable bombers commenced exercises near the US, for the first time since the downfall of the USSR.[133]

In December 2007, United Russia—the governing party that supports the policies of Putin—won 64.24% of the popular vote in their run for State Duma according to election preliminary results.[134] United Russia’s victory in the December 2007 elections was seen by many as an indication of strong popular support of the then Russian leadership and its policies.[135][136] On 11 February 2008, while Putin addressed the 15th anniversary party of Gazprom, its employees threatened Ukraine with a stoppage of flow.[133]

On 4 April 2008 at the NATO Bucharest summit, invitee Putin told George W. Bush and other conference delegates: “We view the appearance of a powerful military bloc on our border as a direct threat to the security of our nation. The claim that this process is not directed against Russia will not suffice. National security is not based on promises.”[133]

2008–2012: Second premiership

Further information: Vladimir Putin’s Second Cabinet and Medvedev–Putin tandemocracy

See also: Presidency of Dmitry Medvedev

Putin was barred from a third consecutive term by the Constitution. First Deputy Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev was elected his successor. In a power-switching operation on 8 May 2008, only a day after handing the presidency to Medvedev, Putin was appointed Prime Minister of Russia, maintaining his political dominance.[137]

Putin has said that overcoming the consequences of the world economic crisis was one of the two main achievements of his second premiership.[115] The other was stabilizing the size of Russia’s population between 2008 and 2011 following a long period of demographic collapse that began in the 1990s.[115]

The Russo-Georgian War that both started and finished in August 2008 was imagined by Putin and communicated to his staff as early 2006.[138]

It was during this premiership that the 2009 Russia–Ukraine gas dispute occurred, and Putin controlled the Gazprom chessboard, according to Andriy Kobolyev, who was then an advisor to the CEO of the Ukrainian Naftogaz utility. Putin observed at a German trade show in 2010 that if his hosts did not want Russia’s natural gas nor nuclear power they could always heat with wood, and for that they would need to log Siberia.[133]

At the United Russia Congress in Moscow on 24 September 2011, Medvedev officially proposed that Putin stand for the presidency in 2012, an offer Putin accepted. Given United Russia’s near-total dominance of Russian politics, many observers believed that Putin was assured of a third term. The move was expected to see Medvedev stand on the United Russia ticket in the parliamentary elections in December, with a goal of becoming prime minister at the end of his presidential term.[139]

After the parliamentary elections on 4 December 2011, tens of thousands of Russians engaged in protests against alleged electoral fraud, the largest protests in Putin’s time. Protesters criticized Putin and United Russia and demanded annulment of the election results.[140] Those protests sparked the fear of a colour revolution in society.[141] Putin allegedly organized a number of paramilitary groups loyal to himself and to the United Russia party in the period between 2005 and 2012.[142]

2012–2018: Third presidential term

See also: Vladimir Putin 2012 presidential campaign

Shortly after Medvedev took office in 2008, presidential terms were extended from four to six years, effective with the 2012 election.[143]

On 24 September 2011, while speaking at the United Russia party congress, Medvedev announced that he would recommend the party nominate Putin as its presidential candidate. He also revealed that the two men had long ago cut a deal to allow Putin to run for president in 2012.[144] This switch was termed by many in the media as “Rokirovka”, the Russian term for the chess move “castling“.[145]

On 4 March 2012, Putin won the 2012 Russian presidential election in the first round, with 63.6% of the vote, despite widespread accusations of vote-rigging.[146][147][148] Opposition groups accused Putin and the United Russia party of fraud.[149] While efforts to make the elections transparent were publicized, including the usage of webcams in polling stations, the vote was criticized by the Russian opposition and by international observers from the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe for procedural irregularities.[150]

Anti-Putin protests took place during and directly after the presidential campaign. The most notorious protest was the Pussy Riot performance on 21 February, and subsequent trial.[151] An estimated 8,000–20,000 protesters gathered in Moscow on 6 May,[152][153] when eighty people were injured in confrontations with police,[154] and 450 were arrested, with another 120 arrests taking place the following day.[155] A counter-protest of Putin supporters occurred which culminated in a gathering of an estimated 130,000 supporters at the Luzhniki Stadium, Russia’s largest stadium.[156] Some of the attendees stated that they had been paid to come, were forced to come by their employers, or were misled into believing that they were going to attend a folk festival instead.[157][158][159] The rally is considered to be the largest in support of Putin to date.[160]

Putin’s presidency was inaugurated in the Kremlin on 7 May 2012.[161] On his first day as president, Putin issued 14 presidential decrees, which are sometimes called the “May Decrees” by the media, including a lengthy one stating wide-ranging goals for the Russian economy. Other decrees concerned education, housing, skilled labor training, relations with the European Union, the defense industry, inter-ethnic relations, and other policy areas dealt with in Putin’s program articles issued during the presidential campaign.[162]

In 2012 and 2013, Putin and the United Russia party backed stricter legislation against the LGBT community, in Saint Petersburg, Archangelsk, and Novosibirsk; a law called the Russian gay propaganda law, that is against “homosexual propaganda” (which prohibits such symbols as the rainbow flag,[163][164] as well as published works containing homosexual content) was adopted by the State Duma in June 2013.[165][166] Responding to international concerns about Russia’s legislation, Putin asked critics to note that the law was a “ban on the propaganda of pedophilia and homosexuality” and he stated that homosexual visitors to the 2014 Winter Olympics should “leave the children in peace” but denied there was any “professional, career or social discrimination” against homosexuals in Russia.[167]

In June 2013, Putin attended a televised rally of the All-Russia People’s Front where he was elected head of the movement,[168] which was set up in 2011.[169] According to journalist Steve Rosenberg, the movement is intended to “reconnect the Kremlin to the Russian people” and one day, if necessary, replace the increasingly unpopular United Russia party that currently backs Putin.[170]

Annexation of Crimea

Main article: Annexation of Crimea by the Russian Federation

Further information: Russia–Ukraine relations, Russo-Ukrainian War, War in Donbas (2014–2022), Normandy Format, and Minsk agreements

In February 2014, Russia made several military incursions into Ukrainian territory. After the Euromaidan protests and the fall of Ukrainian president Viktor Yanukovych, Russian soldiers without insignias took control of strategic positions and infrastructure within the Ukrainian territory of Crimea. Russia then annexed Crimea and Sevastopol after a referendum in which, according to official results, Crimeans voted to join the Russian Federation.[171][172][173] Subsequently, demonstrations against Ukrainian Rada legislative actions by pro-Russian groups in the Donbas area of Ukraine escalated into the Russo-Ukrainian War between the Ukrainian government and the Russia-backed separatist forces of the self-declared Donetsk and Luhansk People’s Republics. In August 2014,[174] Russian military vehicles crossed the border in several locations of Donetsk Oblast.[175][176][177] The incursion by the Russian military was seen by Ukrainian authorities as responsible for the defeat of Ukrainian forces in early September.[178][179]

In October 2014, Putin addressed Russian security concerns in Sochi at the Valdai International Discussion Club. In November 2014, the Ukrainian military reported intensive movement of troops and equipment from Russia into the separatist-controlled parts of eastern Ukraine.[180] The Associated Press reported 80 unmarked military vehicles on the move in rebel-controlled areas.[181] An OSCE Special Monitoring Mission observed convoys of heavy weapons and tanks in DPR-controlled territory without insignia.[182] OSCE monitors further stated that they observed vehicles transporting ammunition and soldiers’ dead bodies crossing the Russian-Ukrainian border under the guise of humanitarian-aid convoys.[183]

As of early August 2015, the OSCE observed over 21 such vehicles marked with the Russian military code for soldiers killed in action.[184] According to The Moscow Times, Russia has tried to intimidate and silence human-rights workers discussing Russian soldiers’ deaths in the conflict.[185] The OSCE repeatedly reported that its observers were denied access to the areas controlled by “combined Russian-separatist forces”.[186]

In October 2015, The Washington Post reported that Russia had redeployed some of its elite units from Ukraine to Syria in recent weeks to support Syrian president Bashar al-Assad.[187] In December 2015, Putin admitted that Russian military intelligence officers were operating in Ukraine.[188]

The Moscow Times quoted pro-Russian academic Andrei Tsygankov as saying that many members of the international community assumed that Putin’s annexation of Crimea had initiated a completely new type of Russian foreign policy[189][190] and that his foreign policy had shifted “from state-driven foreign policy” to taking an offensive stance to recreate the Soviet Union. In July 2015, he opined that this policy shift could be understood as Putin trying to defend nations in Russia’s sphere of influence from “encroaching western power”.[191]

Intervention in Syria

Main articles: Russian intervention in the Syrian civil war and Russian involvement in the Syrian civil war

See also: Foreign involvement in the Syrian civil war and Russia–Syria relations

On 30 September 2015, President Putin authorized Russian military intervention in the Syrian civil war, following a formal request by the Syrian government for military help against rebel and jihadist groups.[192]

The Russian military activities consisted of air strikes, cruise missile strikes and the use of front line advisors and Russian special forces against militant groups opposed to the Syrian government, including the Syrian opposition, as well as Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL), al-Nusra Front (al-Qaeda in the Levant), Tahrir al-Sham, Ahrar al-Sham, and the Army of Conquest.[193][194] After Putin’s announcement on 14 March 2016 that the mission he had set for the Russian military in Syria had been “largely accomplished” and ordered the withdrawal of the “main part” of the Russian forces from Syria,[195] Russian forces deployed in Syria continued to actively operate in support of the Syrian government.[196]

Russia’s interference in the 2016 US election

Main articles: Russian interference in the 2016 United States elections and Timeline of Russian interference in the 2016 United States elections

See also: Russia–United States relations

In January 2017, a U.S. intelligence community assessment expressed high confidence that Putin personally ordered an influence campaign, initially to denigrate Hillary Clinton and to harm her electoral chances and potential presidency, then later developing “a clear preference” for Donald Trump.[197] Trump consistently denied any Russian interference in the U.S. election,[198][199][200] as did Putin in December 2016,[201] March 2017,[202] June 2017,[203][204][205] and July 2017.[206]

Putin later stated that interference was “theoretically possible” and could have been perpetrated by “patriotically minded” Russian hackers,[207] and on another occasion claimed “not even Russians, but Ukrainians, Tatars or Jews, but with Russian citizenship” might have been responsible.[208] In July 2018, The New York Times reported that the CIA had long nurtured a Russian source who eventually rose to a position close to Putin, allowing the source to pass key information in 2016 about Putin’s direct involvement.[209] Putin continued similar attempts in the 2020 U.S. presidential election.[210]

2018–2024: Fourth presidential term

See also: Vladimir Putin 2018 presidential campaign

Putin won the 2018 Russian presidential election with more than 76% of the vote.[211] His fourth term began on 7 May 2018,[212] and will last until 2024.[213] On the same day, Putin invited Dmitry Medvedev to form a new government.[214] On 15 May 2018, Putin took part in the opening of the movement along the highway section of the Crimean bridge.[215] On 18 May 2018, Putin signed decrees on the composition of the new Government.[216] On 25 May 2018, Putin announced that he would not run for president in 2024, justifying this in compliance with the Russian Constitution.[217] On 14 June 2018, Putin opened the 21st FIFA World Cup, which took place in Russia for the first time. On 18 October 2018, Putin said Russians will ‘go to Heaven as martyrs’ in the event of a nuclear war as he would only use nuclear weapons in retaliation.[218] In September 2019, Putin’s administration interfered with the results of Russia’s nationwide regional elections and manipulated it by eliminating all candidates in the opposition. The event that was aimed at contributing to the ruling party, United Russia‘s victory, also contributed to inciting mass protests for democracy, leading to large-scale arrests and cases of police brutality.[219]

On 15 January 2020, Medvedev and his entire government resigned after Putin’s 2020 Presidential Address to the Federal Assembly. Putin suggested major constitutional amendments that could extend his political power after presidency.[220][221] At the same time, on behalf of Putin, he continued to exercise his powers until the formation of a new government.[222] Putin suggested that Medvedev take the newly created post of deputy chairman of the Security Council.[223]

On the same day, Putin nominated Mikhail Mishustin, head of the country’s Federal Tax Service for the post of prime minister. The next day, he was confirmed by the State Duma to the post,[224][225] and appointed prime minister by Putin’s decree.[226] This was the first time ever that a prime minister was confirmed without any votes against. On 21 January 2020, Mishustin presented to Putin a draft structure of his Cabinet. On the same day, the president signed a decree on the structure of the Cabinet and appointed the proposed ministers.[227][228][229]

COVID-19 pandemic

Main article: COVID-19 pandemic in Russia

On 15 March 2020, Putin instructed to form a Working Group of the State Council to counteract the spread of COVID-19. Putin appointed Moscow Mayor Sergey Sobyanin as the head of the group.[230]

On 22 March 2020, after a phone call with Italian prime minister Giuseppe Conte, Putin arranged the Russian army to send military medics, special disinfection vehicles and other medical equipment to Italy, which was the European country hardest hit by the COVID-19 pandemic.[231] Putin began working remotely from his office at Novo-Ogaryovo. According to Dmitry Peskov, Putin passed daily tests for COVID-19, and his health was not in danger.[232][233]

On 25 March, President Putin announced in a televised address to the nation that the 22 April constitutional referendum would be postponed due to COVID-19.[234] He added that the next week would be a nationwide paid holiday and urged Russians to stay at home.[235][236] Putin also announced a list of measures of social protection, support for small and medium-sized enterprises, and changes in fiscal policy.[237] Putin announced the following measures for microenterprises, small- and medium-sized businesses: deferring tax payments (except Russia’s value-added tax) for the next six months, cutting the size of social security contributions in half, deferring social security contributions, deferring loan repayments for the next six months, a six-month moratorium on fines, debt collection, and creditors’ applications for bankruptcy of debtor enterprises.[238][239]

On 2 April 2020, Putin again issued an address in which he announced prolongation of the non-working time until 30 April.[240] Putin likened Russia’s fight against COVID-19 to Russia’s battles with invading Pecheneg and Cuman steppe nomads in the 10th and 11th centuries.[241] In a 24 to 27 April Levada poll, 48% of Russian respondents said that they disapproved of Putin’s handling of the COVID-19 pandemic,[242] and his strict isolation and lack of leadership during the crisis was widely commented as sign of losing his “strongman” image.[243][244]

In June 2021, Putin said he was fully vaccinated against the disease with the Sputnik V vaccine, emphasising that while vaccinations should be voluntary, making them mandatory in some professions would slow down the spread of COVID-19.[246] In September, Putin entered self-isolation after people in his inner circle tested positive for the disease.[247] According to a report by the Wall Street Journal, Putin’s inner circle of advisors shrank during the COVID-19 lockdown to a small number of hawkish advisers.[248]

Constitutional referendum and amendments

Main article: 2020 Russian constitutional referendum

Putin signed an executive order on 3 July 2020 to officially insert amendments into the Russian Constitution, allowing him to run for two additional six-year terms. These amendments took effect on 4 July 2020.[249]

In 2020 and 2021, protests were held in the Khabarovsk Krai in Russia’s Far East in support of arrested regional governor Sergei Furgal.[250] The 2020 Khabarovsk Krai protests became increasingly anti-Putin over time.[251][252] A July 2020 Levada poll found that 45% of surveyed Russians supported the protests.[253] On 22 December 2020, Putin signed a bill giving lifetime prosecutorial immunity to Russian ex-presidents.[254][255]

Iran trade deal

See also: Iran–Russia relations

Putin met Iran President Ebrahim Raisi in January 2022 to lay the groundwork for a 20-year deal between the two nations.[256]

2021–2022 Russo-Ukrainian crisis

Main article: Prelude to the Russian invasion of Ukraine

In July 2021, Putin published an essay titled On the Historical Unity of Russians and Ukrainians, in which he states that Belarusians, Ukrainians and Russians should be in one All-Russian nation as a part of the Russian world and are “one people” whom “forces that have always sought to undermine our unity” wanted to “divide and rule”.[257] The essay denies the existence of Ukraine as an independent nation.[258][259]

On 30 November 2021, Putin stated that an enlargement of NATO in Ukraine would be a “red line” issue for Russia.[260][261][262] The Kremlin repeatedly denied that it had any plans to invade Ukraine,[263][264][265] and Putin himself dismissed such fears as “alarmist”.[266] On 21 February 2022, Putin signed a decree recognizing the two self-proclaimed separatist republics in Donbas as independent states and made an address concerning the events in Ukraine.[267]

Putin was persuaded to invade Ukraine by a small group of his closest associates, especially Nikolai Patrushev, Yury Kovalchuk and Alexander Bortnikov.[268] According to sources close to the Kremlin, most of Putin’s advisers and associates opposed the invasion, but Putin overruled them. The invasion of Ukraine had been planned for almost a year.[269]

Full-scale invasion of Ukraine (2022–present)

Main articles: Russian invasion of Ukraine and Timeline of the Russian invasion of Ukraine

On 24 February, Putin in a televised address announced a “special military operation“[270] (SMO) in Ukraine,[271][272] launching a full-scale invasion of the country.[273] Citing a purpose of “denazification“, he claimed to be doing this to protect people in the predominantly Russian-speaking region of Donbas who, according to Putin, faced “humiliation and genocide” from Ukraine for eight years.[274] Minutes after the speech, he launched a war to gain control of the remainder of the country and overthrow the elected government under the pretext that it was run by Nazis.[275][276] Russia’s invasion was met with international condemnation.[277][278][279] International sanctions were widely imposed against Russia, including against Putin personally.[280][281] The invasion also led to numerous calls for Putin to be pursued with war crime charges.[282][283][284][285] The International Criminal Court (ICC) stated that it would investigate the possibility of war crimes in Ukraine since late 2013,[286] and the United States pledged to help the ICC to prosecute Putin and others for war crimes committed during the invasion of Ukraine.[287] In response to these condemnations, Putin put the Strategic Rocket Forces‘s nuclear deterrence units on high alert.[288] By early March, U.S. intelligence agencies determined that Putin was “frustrated” by slow progress due to an unexpectedly strong Ukrainian defense.[289]

On 4 March, Putin signed into law a bill introducing prison sentences of up to 15 years for those who publish “knowingly false information” about the Russian military and its operations, leading to some media outlets in Russia to stop reporting on Ukraine.[290] On 7 March, as a condition for ending the invasion, the Kremlin demanded Ukraine’s neutrality, recognition of Crimea as Russian territory, and recognition of the self-proclaimed republics of Donetsk and Luhansk as independent states.[291][292] On 8 March Putin promised that no conscripts would be used in the SMO.[293] On 16 March, Putin issued a warning to Russian “traitors” who he said the West wanted to use as a “fifth column” to destroy Russia.[294][295] Following the invasion of Ukraine in 2022,[296] Russia’s long-term demographic crisis deepened due to emigration, lower fertility rates and war-related casualties.[297]

As early as 25 March, the UN Office of the High Commissioner on Human Rights reported that Putin ordered a “kidnapping” policy, whereby Ukrainian nationals who did not cooperate with the Russian takeover of their homeland were victimized by FSB agents.[298][299] On 28 March, Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelenskyy said he was “99.9 percent sure” that Putin thought the Ukrainians would welcome the invading forces with “flowers and smiles” while he opened the door to negotiations on the offer that Ukraine would henceforth be a non-aligned state.[300]

On 21 September, Putin announced a partial mobilization, following a successful Ukrainian counteroffensive in Kharkiv and the announcement of annexation referendums in Russian-occupied Ukraine.[301]

On 30 September, Putin signed decrees which annexed Donetsk, Luhansk, Zaporizhzhia, and Kherson Oblasts of Ukraine into the Russian Federation. The annexations are not recognized by the international community and are illegal under international law.[302] On 11 November the same year, Ukraine liberated Kherson.[303]

In December 2022, he said that a war against Ukraine could be a “long process”.[304] Hundreds of thousands of people have been killed in the Russo-Ukrainian War since February 2022.[305][306] In January 2023, Putin cited recognition of Russia’s sovereignty over the annexed territories as a condition for peace talks with Ukraine.[307]

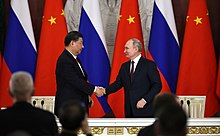

On 20–22 March 2023, Chinese president Xi Jinping visited Russia and met with Vladimir Putin both in official and unofficial capacity.[308] It was the first international meeting of Vladimir Putin since the International Criminal Court issued a warrant for his arrest.[309]

In May 2023, South Africa announced that it would grant diplomatic immunity to Vladimir Putin to attend the 15th BRICS Summit in Johannesburg despite the ICC arrest warrant.[310] In July 2023, South African president Cyril Ramaphosa announced that Putin would not attend the summit “by mutual agreement” and would instead send Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov.[311]

In July 2023, Putin threatened to take “reciprocal action” if Ukraine used US-supplied cluster munitions during a Ukrainian counter-offensive against Russian forces in occupied southeastern Ukraine.[312] On 17 July 2023, Putin withdrew from a deal that allowed Ukraine to export grain across the Black Sea despite a wartime blockade,[313] risking deepening the global food crisis and antagonizing neutral countries in the Global South.[314]

On 27–28 July, Putin hosted the 2023 Russia–Africa Summit in St. Petersburg,[315] which was attended by delegations from more than 40 African countries.[316] As of August 2023, the total number of Russian and Ukrainian soldiers killed or wounded during the Russian invasion of Ukraine was nearly 500,000.[317]

Putin condemned the 2023 Hamas-led attack on Israel that sparked the Israel–Hamas war and said Israel had a right to defend itself, but also criticized Israel’s response and said Israel should not besiege the Gaza Strip in the way Nazi Germany besieged Leningrad. Putin suggested that Russia could be a mediator in the conflict.[318][319] Putin blamed the war on the United States’ failed foreign policy in the Middle East and expressed concern over the suffering of Palestinian children in the Gaza Strip.[320] In a December 2023 call between Israeli prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu and Putin, Netanyahu expressed displeasure over Russia’s conduct at the United Nations and described its growing ties to Iran as dangerous.[321]

On 22 November 2023, Putin claimed that Russia was always “ready for talks” to end the “tragedy” of the war in Ukraine, and accused the Ukrainian leadership of rejecting peace talks with Russia.[322] However, on 14 December 2023, Putin said, “there will only be peace in Ukraine when we achieve our aims”, which he said are “de-Nazification, de-militarization and a neutral status” of Ukraine.[323] On 23 December 2023, The New York Times reported that Putin has been signaling through intermediaries since at least September 2022 that “he is open to a ceasefire that freezes the fighting along the current lines”.[324]

ICC arrest warrant

Main article: International Criminal Court arrest warrants for Russian figures

See also: International Criminal Court investigation in Ukraine and Child abductions in the Russian invasion of Ukraine

On 17 March 2023, the International Criminal Court issued a warrant for Putin’s arrest,[325][326][327][328] alleging that Putin held criminal responsibility in the illegal deportation and transfer of children from Ukraine to Russia during the Russian invasion of Ukraine.[329][330][331]

It was the first time that the ICC had issued an arrest warrant for the head of state of one of the five Permanent Members of the United Nations Security Council,[325] (the world’s five principal nuclear powers).[332]

The ICC simultaneously issued an arrest warrant for Maria Lvova-Belova, Commissioner for Children’s Rights in the Office of the President of the Russian Federation. Both are charged with:

:…the war crime of unlawful deportation of population (children) and that of unlawful transfer of population (children) from occupied areas of Ukraine to the Russian Federation,…[327] …for their publicized program, since 24 February 2022, of forced deportations of thousands of unaccompanied Ukrainian children to Russia, from areas of eastern Ukraine under Russian control.[325][327]

Russia has maintained that the deportations were humanitarian efforts to protect orphans and other children abandoned in the conflict region.[325]

2023 Wagner rebellion

Main article: Wagner Group rebellion

On 23 June 2023, the Wagner Group, a Russian paramilitary organization, rebelled against the government of Russia. The revolt arose amidst escalating tensions between the Russian Ministry of Defense and Yevgeny Prigozhin, the leader of Wagner.[333]

Prigozhin portrayed the rebellion as a response to an alleged attack on his forces by the ministry.[334][335] He dismissed the government’s justification for invading Ukraine,[336] blamed Defense Minister Sergei Shoigu for the country’s military shortcomings,[337] and accused him of waging the war for the benefit of Russian oligarchs.[338][339] In a televised address on 24 June, Russian president Vladimir Putin denounced Wagner’s actions as treason and pledged to quell the rebellion.[335][340]

Prigozhin’s forces seized control of Rostov-on-Don and the Southern Military District headquarters and advanced towards Moscow in an armored column.[341] Following negotiations with Belarusian president Alexander Lukashenko,[342] Prigozhin agreed to stand down[343] and, late on 24 June, began withdrawing from Rostov-on-Don.[344]

On 23 August 2023, exactly two months after the rebellion, Prigozhin was killed along with nine other people when a business jet crashed in Tver Oblast, north of Moscow.[345] Western intelligence reported that the crash was probably caused by an explosion on board, and it is widely suspected that the Russian state were involved.[346]

2024–present: Fifth presidential term

See also: Vladimir Putin 2024 presidential campaignPutin’s speech on the Crocus City Hall attack

Putin won the 2024 Russian presidential election with 88.48% of the vote. International observers did not consider the election to be either free or fair,[347] with Putin having increased political repressions after launching his full-scale war with Ukraine in 2022.[348][349] The elections were also held in the Russian-occupied territories of Ukraine.[349] There were reports of irregularities, including ballot stuffing and coercion,[350] with statistical analysis suggesting unprecedented levels of fraud in the 2024 elections.[351][352][353]

On 22 March 2024, the Crocus City Hall attack took place, causing the deaths of at least 145 people and injuring at least 551 more.[354][355] It was the deadliest terrorist attack on Russian soil since the Beslan school siege in 2004.[356][357]

On 7 May 2024, Putin was inaugurated as president of Russia for the fifth time.[358] According to analysts, replacing Sergei Shoigu with Andrey Belousov as defense minister signals that Putin wants to transform the Russian economy into a war economy and is “preparing for many more years of war”.[359][360] In May 2024, four Russian sources told Reuters that Putin was ready to end the war in Ukraine with a negotiated ceasefire that would recognize Russia’s war gains and freeze the war on current front lines, as Putin wanted to avoid unpopular steps such as further nationwide mobilization and increased war spending.[361]

On 2 August 2024, Putin pardoned American journalist Evan Gershkovich, opposition figures Vladimir Kara-Murza, Ilya Yashin and others in a prisoner swap with western countries.[362][363][364] The 2024 Ankara prisoner exchange was the most extensive prisoner exchange between Russia and United States since the end of the Cold War, involving the release of twenty-six people.[365]

On 25 September 2024, Putin warned the West that if attacked with conventional weapons Russia would consider a nuclear retaliation,[366] in an apparent deviation from the no first use doctrine.[367] Putin went on to threaten nuclear powers that if they supported another country’s attack on Russia, then they would be considered participants in such an aggression.[368][369] Russia and the United States are the world’s biggest nuclear powers, holding about 88% of the world’s nuclear weapons.[370] Putin has made several implicit nuclear threats since the outbreak of war against Ukraine.[371] Experts say Putin’s announcement is aimed at dissuading the United States, the United Kingdom and France from allowing Ukraine to use Western-supplied long-range missiles such as the Storm Shadow and ATACMS in strikes against Russia.[372]

Domestic policies

Main article: Domestic policy of Vladimir Putin

See also: Freedom of assembly in Russia, Media freedom in Russia, and Internet censorship in Russia

Further information: 2011–2013 Russian protests, 2017–2018 Russian protests, and Bolotnaya Square case

Putin’s domestic policies, particularly early in his first presidency, were aimed at creating a vertical power structure. On 13 May 2000, he issued a decree organizing the 89 federal subjects of Russia into seven administrative federal districts and appointed a presidential envoy responsible for each of those districts (whose official title is Plenipotentiary Representative).[373]

According to Stephen White, under the presidency of Putin, Russia made it clear that it had no intention of establishing a “second edition” of the American or British political system, but rather a system that was closer to Russia’s own traditions and circumstances.[374] Some commentators have described Putin’s administration as a “sovereign democracy“.[375][376][377] According to the proponents of that description (primarily Vladislav Surkov), the government’s actions and policies ought above all to enjoy popular support within Russia itself and not be directed or influenced from outside the country.[378]

The practice of the system is characterized by Swedish economist Anders Åslund as manual management, commenting: “After Putin resumed the presidency in 2012, his rule is best described as ‘manual management’ as the Russians like to put it. Putin does whatever he wants, with little consideration to the consequences with one important caveat. During the Russian financial crash of August 1998, Putin learned that financial crises are politically destabilizing and must be avoided at all costs. Therefore, he cares about financial stability.”[379]

The period after 2012 saw mass protests against the falsification of elections, censorship and toughening of free assembly laws. In July 2000, according to a law proposed by Putin and approved by the Federal Assembly of Russia, Putin gained the right to dismiss the heads of the 89 federal subjects. In 2004, the direct election of those heads (usually called “governors”) by popular vote was replaced with a system whereby they would be nominated by the president and approved or disapproved by regional legislatures.[380][381]

This was seen by Putin as a necessary move to stop separatist tendencies and get rid of those governors who were connected with organised crime.[382] This and other government actions effected under Putin’s presidency have been criticized by many independent Russian media outlets and Western commentators as anti-democratic.[383][384]

During his first term in office, Putin opposed some of the Yeltsin-era business oligarchs, as well as his political opponents, resulting in the exile or imprisonment of such people as Boris Berezovsky, Vladimir Gusinsky, and Mikhail Khodorkovsky; other oligarchs such as Roman Abramovich and Arkady Rotenberg are friends and allies with Putin.[385] Putin succeeded in codifying land law and tax law and promulgated new codes on labor, administrative, criminal, commercial and civil procedural law.[386] Under Medvedev’s presidency, Putin’s government implemented some key reforms in the area of state security, the Russian police reform and the Russian military reform.[387]

Economic, industrial, and energy policies

See also: Economy of Russia, Energy policy of Russia, Great Recession in Russia, Russian financial crisis (2014–2016), and Economic impact of the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine

Sergey Guriyev, when talking about Putin’s economic policy, divided it into four distinct periods: the “reform” years of his first term (1999–2003); the “statist” years of his second term (2004—the first half of 2008); the world economic crisis and recovery (the second half of 2008–2013); and the Russo-Ukrainian War, Russia’s growing isolation from the global economy, and stagnation (2014–present).[388]

In 2000, Putin launched the “Programme for the Socio-Economic Development of the Russian Federation for the Period 2000–2010”, but it was abandoned in 2008 when it was 30% complete.[389] Fueled by the 2000s commodities boom including record-high oil prices,[9][10] under the Putin administration from 2000 to 2016, an increase in income in USD terms was 4.5 times.[390] During Putin’s first eight years in office, industry grew substantially, as did production, construction, real incomes, credit, and the middle class.[391][392] A fund for oil revenue allowed Russia to repay Soviet Union’s debts by 2005. Russia joined the World Trade Organization in August 2012.[393]

In 2006, Putin launched an industry consolidation programme to bring the main aircraft-producing companies under a single umbrella organization, the United Aircraft Corporation (UAC).[394][395] In September 2020, the UAC general director announced that the UAC will receive the largest-ever post-Soviet government support package for the aircraft industry in order to pay and renegotiate the debt.[396][397]

In 2014, Putin signed a deal to supply China with 38 billion cubic meters of natural gas per year. Power of Siberia, which Putin has called the “world’s biggest construction project,” was launched in 2019 and is expected to continue for 30 years at an ultimate cost to China of $400bn.[399] The ongoing financial crisis began in the second half of 2014 when the Russian ruble collapsed due to a decline in the price of oil and international sanctions against Russia. These events in turn led to loss of investor confidence and capital flight, although it has also been argued that the sanctions had little to no effect on Russia’s economy.[400][401][402] In 2014, the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project named Putin their Person of the Year for furthering corruption and organized crime.[403][404]

According to Meduza, Putin has since 2007 predicted on a number of occasions that Russia will become one of the world’s five largest economies. In 2013, he said Russia was one of the five biggest economies in terms of gross domestic product but still lagged behind other countries on indicators such as labour productivity.[405] By the end of 2023, Putin planned to spend almost 40% of public expenditures on defense and security.[406]

Environmental policy

Main articles: Environment of Russia and Environmental issues in Russia

In 2004, Putin signed the Kyoto Protocol treaty designed to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.[407] However, Russia did not face mandatory cuts, because the Kyoto Protocol limits emissions to a percentage increase or decrease from 1990 levels and Russia’s greenhouse-gas emissions fell well below the 1990 baseline due to a drop in economic output after the breakup of the Soviet Union.[408]

Religious policy

Main article: Religion in Russia

Putin regularly attends the most important services of the Russian Orthodox Church on the main holy days and has established a good relationship with Patriarchs of the Russian Church, the late Alexy II of Moscow and the current Kirill of Moscow. As president, Putin took an active personal part in promoting the Act of Canonical Communion with the Moscow Patriarchate, signed 17 May 2007, which restored relations between the Moscow-based Russian Orthodox Church and the Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia after the 80-year schism.[409]

Under Putin, the Hasidic Federation of Jewish Communities of Russia became increasingly influential within the Jewish community, partly due to the influence of Federation-supporting businessmen mediated through their alliances with Putin, notably Lev Leviev and Roman Abramovich.[410][411] According to the Jewish Telegraphic Agency, Putin is popular amongst the Russian Jewish community, who see him as a force for stability. Russia’s chief rabbi, Berel Lazar, said Putin “paid great attention to the needs of our community and related to us with a deep respect”.[412] In 2016, Ronald S. Lauder, the president of the World Jewish Congress, also praised Putin for making Russia “a country where Jews are welcome”.[413]

Human rights organizations and religious freedom advocates have criticized the state of religious freedom in Russia.[414] In 2016, Putin oversaw the passage of legislation that prohibited missionary activity in Russia.[414] Nonviolent religious minority groups have been repressed under anti-extremism laws, especially Jehovah’s Witnesses.[415] One of the 2020 amendments to the Constitution of Russia has a constitutional reference to God.[416]

Military development

Main article: 2008 Russian military reform

The resumption of long-distance flights of Russia’s strategic bombers was followed by the announcement by Russian defense minister Anatoliy Serdyukov during his meeting with Putin on 5 December 2007, that 11 ships, including the aircraft carrier Kuznetsov, would take part in the first major navy sortie into the Mediterranean since Soviet times.[417][418]

Key elements of the reform included reducing the armed forces to a strength of one million, reducing the number of officers, centralising officer training from 65 military schools into 10 systemic military training centres, creating a professional NCO corps, reducing the size of the central command, introducing more civilian logistics and auxiliary staff, elimination of cadre-strength formations, reorganising the reserves, reorganising the army into a brigade system, and reorganising air forces into an airbase system instead of regiments.[419]

According to the Kremlin, Putin embarked on a build-up of Russia’s nuclear capabilities because of U.S. president George W. Bush‘s unilateral decision to withdraw from the 1972 Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty.[421] To counter what Putin sees as the United States’ goal of undermining Russia’s strategic nuclear deterrent, Moscow has embarked on a program to develop new weapons capable of defeating any new American ballistic missile defense or interception system. Some analysts believe that this nuclear strategy under Putin has brought Russia into violation of the 1987 Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty.[422]

Accordingly, U.S. president Donald Trump announced the U.S. would no longer consider itself bound by the treaty’s provisions, raising nuclear tensions between the two powers.[422] This prompted Putin to state that Russia would not launch first in a nuclear conflict but that “an aggressor should know that vengeance is inevitable, that he will be annihilated, and we would be the victims of the aggression. We will go to heaven as martyrs”.[423]

Putin has also sought to increase Russian territorial claims in the Arctic and its military presence there. In August 2007, Russian expedition Arktika 2007, part of research related to the 2001 Russian territorial extension claim, planted a flag on the seabed at the North Pole.[424] Both Russian submarines and troops deployed in the Arctic have been increasing.[425][426]

Human rights policy

Main article: Human rights in Russia

See also: Dima Yakovlev Law, Russian foreign agent law, and Russian Internet Restriction Bill

New York City-based NGO Human Rights Watch, in a report entitled Laws of Attrition, authored by Hugh Williamson, the British director of HRW’s Europe & Central Asia Division, has claimed that since May 2012, when Putin was reelected as president, Russia has enacted many restrictive laws, started inspections of non-governmental organizations, harassed, intimidated and imprisoned political activists, and started to restrict critics. The new laws include the “foreign agents” law, which is widely regarded as over-broad by including Russian human rights organizations which receive some international grant funding, the treason law, and the assembly law which penalizes many expressions of dissent.[427][428] Human rights activists have criticized Russia for censoring speech of LGBT activists due to “the gay propaganda law”[429] and increasing violence against LGBT+ people due to the law.[430][431][432]

In 2020, Putin signed a law on labelling individuals and organizations receiving funding from abroad as “foreign agents”. The law is an expansion of “foreign agent” legislation adopted in 2012.[433][434]

As of June 2020, per Memorial Human Rights Center, there were 380 political prisoners in Russia, including 63 individuals prosecuted, directly or indirectly, for political activities (including Alexey Navalny) and 245 prosecuted for their involvement with one of the Muslim organizations that are banned in Russia. 78 individuals on the list, i.e., more than 20% of the total, are residents of Crimea.[435][436] As of December 2022, more than 4,000 people were prosecuted for criticizing the war in Ukraine under Russia’s war censorship laws.[437]

The media

See also: Mass media in Russia, Media freedom in Russia, and Propaganda in Russia

Scott Gehlbach, a professor of Political Science at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, has claimed that since 1999, Putin has systematically punished journalists who challenge his official point of view.[439] Maria Lipman, an American writing in Foreign Affairs claims, “The crackdown that followed Putin’s return to the Kremlin in 2012 extended to the liberal media, which had until then been allowed to operate fairly independently.”[440] The Internet has attracted Putin’s attention because his critics have tried to use it to challenge his control of information.[441] Marian K. Leighton, who worked for the CIA as a Soviet analyst in the 1980s says, “Having muzzled Russia’s print and broadcast media, Putin focused his energies on the Internet.”[442]

Robert W. Orttung and Christopher Walker reported that “Reporters Without Borders, for instance, ranked Russia 148 in its 2013 list of 179 countries in terms of freedom of the press. It particularly criticized Russia for the crackdown on the political opposition and the failure of the authorities to vigorously pursue and bring to justice criminals who have murdered journalists. Freedom House ranks Russian media as “not free”, indicating that basic safeguards and guarantees for journalists and media enterprises are absent.[443] About two-thirds of Russians use television as their primary source of daily news.[444]

In the early 2000s, Putin and his circle began promoting the idea in Russian media that they are the modern-day version of the 17th-century Romanov tsars who ended Russia’s “Time of Troubles“, meaning they claim to be the peacemakers and stabilizers after the fall of the Soviet Union.[445]

Promoting conservatism

| This article is part of a series on |

| Conservatism in Russia |

|---|

| showIdeologies |

| showPrinciples |

| showHistory |

| showIntellectuals |

| showLiterature |

| showPoliticians |

| showParties |

| showOrganisations |

| showMedia |

| showRelated topics |

| vte |